Carolina Caycedo stands in front of the presentation screens on which she has arranged black-and-white photographic copies gathered from her research. Photo by Kate Lain.

In March 2018, The Huntington announced that it was partnering with East Los Angeles College’s Vincent Price Art Museum (VPAM) for the third year of The Huntington’s /five initiative, inviting noted Los Angeles artists Carolina Caycedo and Mario Ybarra Jr. to create new work in response to The Huntington’s collections around the theme of Identity. The project will culminate in an exhibition that will be on view at The Huntington from Nov. 10, 2018 to Feb. 25, 2019. Carribean Fragoza, a freelance journalist who writes about art in Southern California, focuses in this post on Carolina Caycedo.

“Qhip nayr uñtasis sarnaqapxañani” is an aphorism of the Aymara people, an indigenous nation that spans Peru, Bolivia, and Chile. The saying, which roughly translates to “looking back to walk forth,” has served artist Carolina Caycedo as a guiding mantra as she works on her installation pieces for this year’s /five artist residency. Instead of relegating history to a graveyard of the obsolete, Caycedo sees the past, including our deceased ancestors, as existing constantly in the present.

For a segment in Caycedo’s video, dancers drape their bodies over reading tables in the Ahmanson Reading Room. Photo by Kate Lain.

In fact, she sees the past as an active entity that can transform us and the way we perceive reality. “The past is a rebel agent that haunts any certainty of our dominion,” proposes Caycedo, for whom history is never over. The dead remain present to remind us of who we are.

Caycedo’s video installation, a central piece in her project, features performances of hauntings in which dancers evoke the American history of colonization in gardens, galleries, and library reading rooms at The Huntington. The video is accompanied by a presentation screen that consists of three large upright panels that display images and text from Caycedo’s research at The Huntington and beyond.

Dancers move as if entranced on the rocks of a waterfall in The Huntington’s Japanese Garden. Photo by Deborah Miller.

Choreographed by dance artist Marina Magalhães and shot by videographer David de Rozas, the video is centered on brown, black, and queer bodies as they interrupt the pristine spaces of The Huntington in a series of choreographed and improvised movements. The dancers were guided by a few instructions, informed by rituals of work—such as the repetitive actions of tilling the land—and by rituals of spiritual possession.

As the dancers cast themselves over reading tables, for example, Caycedo privileges female bodies, queer bodies, and bodies of color as sources of knowledge more significant than books. In a video segment, the dancers drape their bodies over reading tables in the Ahmanson Reading Room, rolling and stretching sensuously beneath the lit lamps. “Bodies illuminate, not the books,” says Caycedo, as she presses viewers to alter their way of seeing and learning so that it includes sensuality.

Choreographed by dance artist Marina Magalhães and shot by videographer David de Rozas, Caycedo’s video is centered on brown, black, and queer bodies as they interrupt such pristine spaces at The Huntington as the North Vista. Photo by Kate Lain.

The dancers are dressed in rich marigold colors that are traditionally associated with Oxúm, the Afro-Brazilian goddess of fresh water, beauty, luxury, fertility, and sexuality. Caycedo evokes Oxúm again on the rocks of a garden waterfall, as the dancers admire their bodies and move as if entranced by their individual and collective sensuality.

Most notably, the dancers sustain their gaze at the camera. “The gaze of the dancers, or phantoms, is a way to hold the viewer accountable,” says Caycedo, something that she feels is too often missing in history and art. She notes that contemporary dancers are usually expected to perform without ever looking at their audiences, consequently disconnecting the performer from the viewer. For Caycedo, this is a lost opportunity. “There is potential in the gaze. It can shift one’s attention, and the possibility for empathy can exist.”

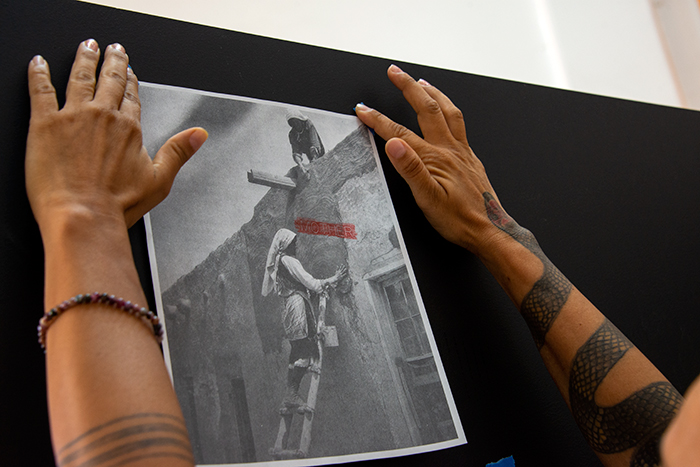

Caycedo, in her studio, attaching a photographic copy gathered from her research to a presentation screen. Photo by Kate Lain.

While Caycedo’s video performances of hauntings aim to challenge fixed notions of reality and history, her presentation screens continue to propel the viewer into further inquiry. She arranges black-and-white photographic copies or transcribed texts and images gathered from her research onto black display screens, where they appear like constellations of stars set in the darkness of space. Inspired by the Mnemosyne Atlas of German art historian and cultural theorist Aby Warburg (1866–1929), Caycedo’s research images are arranged as a montage or collage that allows viewers to create their own endlessly renewed associative maps of meaning. Like the ancients who assigned characters and stories to arbitrary sets of stars, Caycedo’s Mnemosyne incites viewers to stray away from doctrines explaining phenomena by their ends or purposes to construct narratives of their own.

Dancers embrace in front of the Moon Bridge in The Huntington’s Japanese Garden. Photo by Deborah Miller.

Caycedo notes, however, that despite the educational purpose of museums, galleries, libraries, and archives, “they do not necessarily invite you to view the past with a critical eye.” She adds that, rather than inspiring inquiry or engagement, Western traditions often organized information in ways that made everything seem clear and certain. This is precisely what Caycedo’s project aims to subvert.

Carribean Fragoza is a freelance journalist who writes about art in Southern California.