The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Together, We Did This

Posted on Thu., June 25, 2015 by

On June 30, an era draws to a close at The Huntington as President Steve Koblik steps up to his well-deserved retirement. Before we turn the page to the next chapter in our history, Susan Turner-Lowe, vice president for communications and marketing at The Huntington, casts an eye over the life, learning, leadership, and legacy of the man who has guided this institution for nearly 14 years. What follows is an excerpt from her feature article on Koblik in the Spring/Summer 2015 issue of Huntington Frontiers.

Steve Koblik, in 2009, seated in his office at The Huntington, where he has served as president since 2001. Photograph by Lisa Blackburn.

KOBLIK SET HIS SIGHTS ON THE HUNTINGTON DECADES AGO. He was born and raised in Sacramento. His father was an architect; his mother, a homemaker, had been a self-proclaimed flapper in the 1920s—fun-loving, high-spirited, bathtub gin drinking, always in search of adventure, says her only son. That could well explain his indefatigable nature. (He credits his daily naps.)

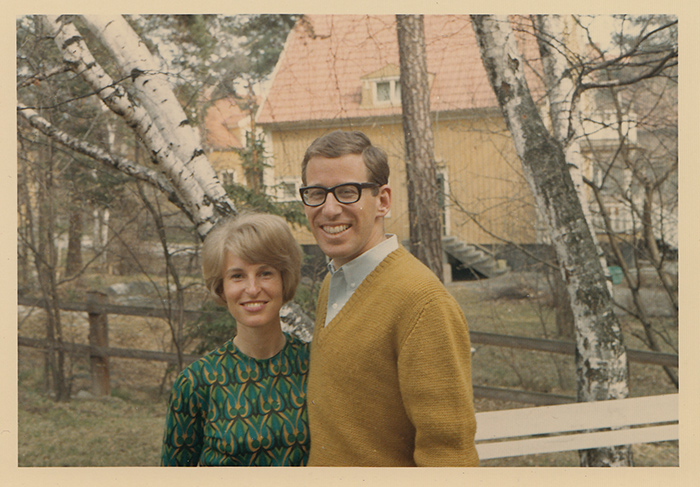

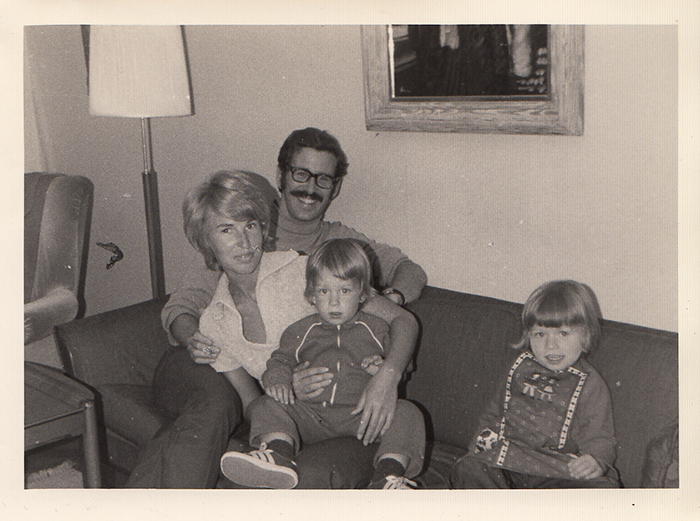

He earned his undergraduate degree at UC Berkeley, got his master’s at University of Stockholm, and holds a Ph.D. from Northwestern. As a graduate student, he homed in on Sweden’s role in World War II and focused his dissertation there; later, he dug into Sweden’s role in the Holocaust and wrote a highly acclaimed book on the topic: The Stones Cry Out. It was in Sweden that he met his future wife, Kerstin Olseni. They have been married 47 years and have two children and four grandchildren.

After living on and off for nine years in Sweden, he returned to Southern California to teach at Pomona. And over time, he became deeply familiar with, and a bit obsessed by, The Huntington.

“In the ’60s, I walked through the doors of the Library with bushy hair and a mustache, wearing clogs. And they took one look at me and said, ‘Steve, you’re a nice guy. But we don’t let people like you in this place.’” A bit of a bohemian by looks, he was nevertheless a serious scholar, interested in the history of Southern California and wanting to do some research on Henry Huntington himself. The closed atmosphere—one that suggested clubbiness and exclusivity—irked him. He wouldn’t let it go.

He remembers telling friends, “I’d like to be president of The Huntington one day.”

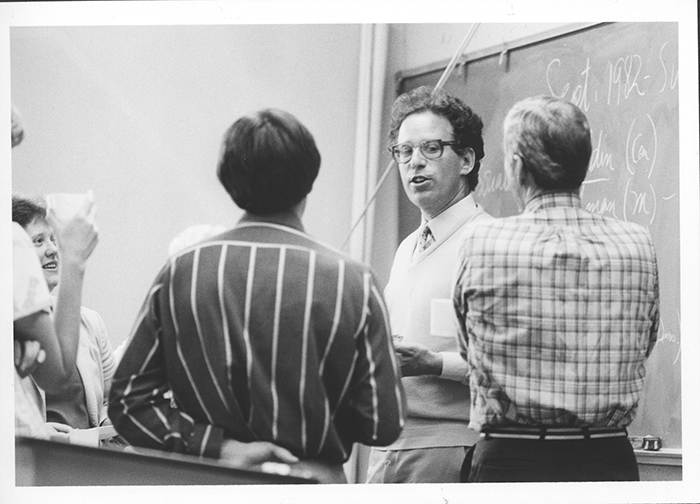

In the meantime, he won one teaching prize after another at Pomona, became dean of the faculty at Scripps, and then went on to take the helm at Reed College in Portland, Ore. He held the presidency there for nine years.

And then, by a remarkable confluence of events, The Huntington presidency opened up, and Koblik was in perfect position for the job.

Koblik with his wife, Kerstin, and their two children in 1971.

HE MOVED FROM REED TO THE HUNTINGTON in the fall of 2001. Sept. 11, in fact, was the day of Koblik’s first board meeting. One might have seen this as a really bad omen, but Koblik saw it as a time for strength and courage, and a time to pull together in the wake of the terrorist acts. So instead of closing The Huntington for the day and sending people home, he kept the gates open and watched as visitors came by the dozens, then the hundreds—searching for solace, for comfort, for meaning.

It is the essence of the place, and something Koblik realizes deeply. It’s sometimes hard to articulate exactly what The Huntington does for people. It doesn’t cure cancer; it isn’t in the business of providing meals to the homeless; it doesn’t take in stray animals; it’s not the kind of nonprofit that pulls at one’s heartstrings the way the Red Cross does. It’s not trying to be that. And it’s not like a college or university in the conventional sense, even though it is involved in research and education. But, it does not award degrees; it has no alumni. So it can be a little challenging to articulate what brings people to The Huntington and fuels their passion and commitment to the place.

Professor Koblik in a Pomona College classroom in 1983. Photograph courtesy of Pomona College Archives.

Koblik explains his own passion for it in this way: “The Huntington is the keeper of the flame. We collect and preserve culture, and we celebrate human achievement, and that is fundamental if you want to know who we are as a people and where we might be going.” The Huntington’s collections explain so much about how the United States came to be—warts and all—with historical, literary, and artistic documentation that speaks to the early formulations of the rule of law (think Magna Carta); the Founding Fathers, slavery and the Civil War, the mission period and Native Americans, expedition and discovery, railroads, women’s suffrage, immigration, exclusion, innovation and invention, exploitation and emancipation. And the breadth and depth of The Huntington’s collections is simply astonishing: from micro to macro. Here is a library with nine million items, and a European and American art collection that spans six centuries. And all this is set among beautiful, world-renowned botanical gardens with 15,000 species, many of them rare and endangered.

Back when Koblik was organizing The Huntington’s first comprehensive fundraising campaign, the renowned AIDS researcher David Ho said, “We give people life. You give people meaning in life.”

Koblik, in 1995, talking with students at Reed College, where he was president from 1992 to 2001. Photograph courtesy of Special Collections, Eric V. Hauser Memorial Library, Reed College.

THE AFTERNOON BEFORE KOBLIK'S FIRST DAY ON THE JOB, he walked over to the mausoleum, the gravesite of Henry and Arabella Huntington. “He wanted some quiet time there,” says Kerstin. “He had said he wanted to think deeply about what Henry Huntington might do, and how he would want the institution run.”

In some respects, Koblik’s game has been a collaboration, in part, with Henry Huntington himself—constantly thinking about what the founder’s intentions might have been and whether Koblik’s decisions and the institution’s direction have lined up with those intentions. But the collaborative spirit goes deeper and wider than that—with area institutions, disparate groups of donors, his boards, the staff. “Together,” he says, “we did this.”

You can read the full article online.

Susan Turner-Lowe is vice president for communications and marketing at The Huntington.