The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Of Rats and Men

Posted on Wed., March 27, 2019 by

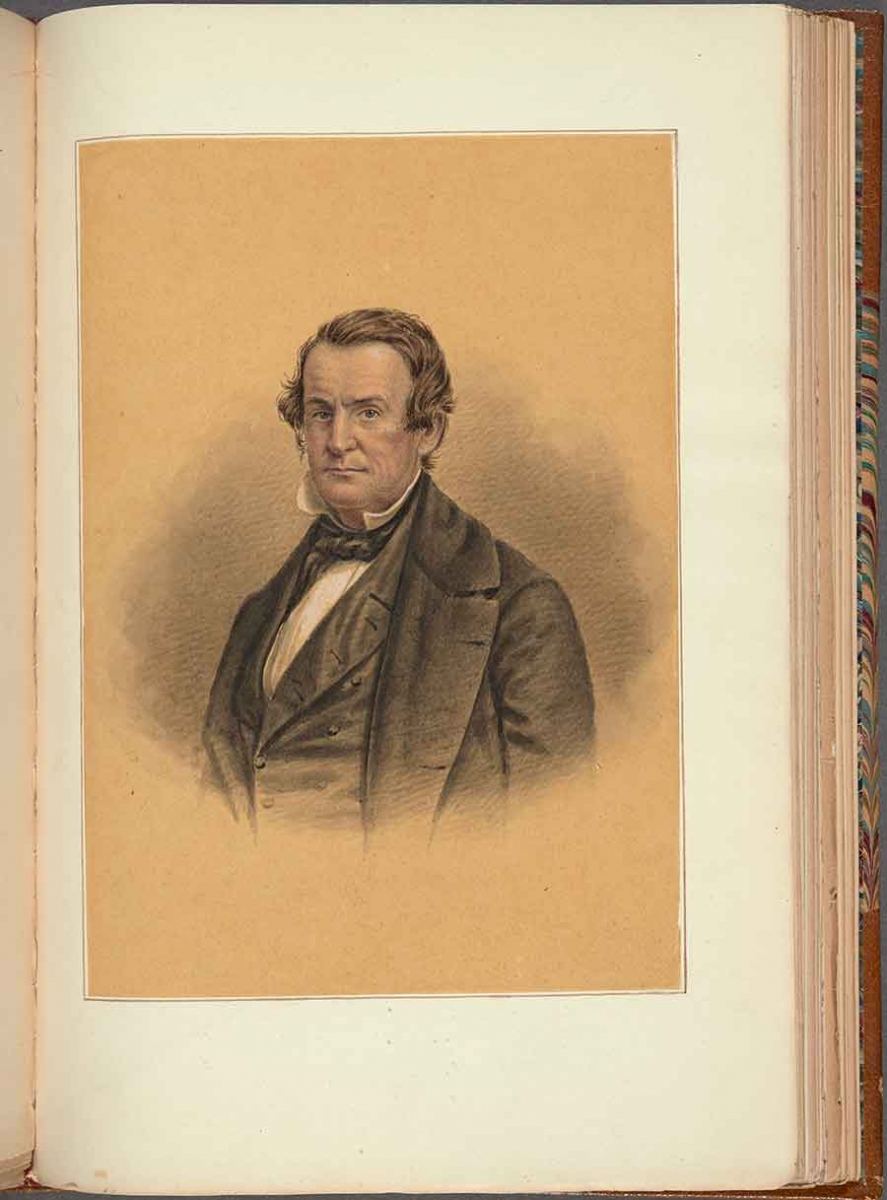

Henry Meigs. Lithograph after the daguerreotype by M.M. Lawrence, 1854. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In the spring of 1838, Henry Meigs (1782–1861)—a veteran of the War of 1812, former U.S. Representative, and a successful lawyer—discovered that he was sharing his house on 51 Perry Street in New York City, in what is now the West Village, with a family of rats who took to "eating holes in many rooms & ravaging my closets." Meigs duly recorded the discovery in his diary, now at The Huntington.

Countless New Yorkers would, no doubt, sympathize. The ubiquity of the Norwegian or brown rat (Rattus norvegicus) is a trademark of the Big Apple. (The New York rat has achieved the apotheosis of 21st-century notoriety—its own Wikipedia article.)

Today’s New Yorkers, however, would find Meigs’s methods of pest control a bit unorthodox. He chose to forego mousetraps, guns, poison, or the services of a cat or a well-trained rat terrier. Instead, he replicated “the experiment upon the manner of Rats” that he first ran in 1811, when he was a young lawyer living on 48 Franklin Street.

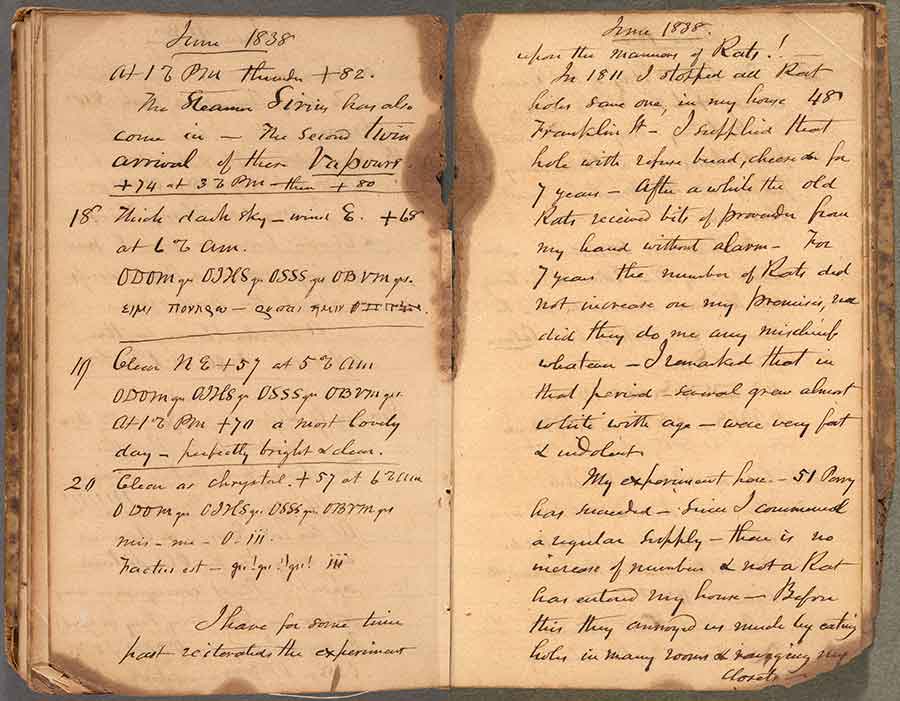

The method was simple: All he had to do was stop “all rat holes, save one” and then stuff the remaining hole with “refuse bread, cheese, etc.” Seven years later, in 1818, Meigs was happy to report that “the number of Rats did not increase on my premises, nor did they do any mischief whatever.” Several “grew almost white with age” and became “very fat and indolent,” and some “old rats received bits of provisions from my hand without alarm.”

The experiment worked like a charm again two decades later. On June 20, 1838, Meigs reported with a great deal of satisfaction that “My Experiment here—51 Perry—has succeeded.” Although, as he noted, “My Rats consume nearly a pound [of] provisions per day,” the expense paid off, for “not a Rat entered my home,” with the sole exception of one cheeky rodent who did stray into his study, but, as Meigs hastened to add, “went out at my request.”

Henry Meigs writes about his experiment with rats in an entry of his diary for May 15, 1837–Dec. 16, 1838. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The sense of decorum was not the only thing that impressed Meigs about his furry housemates. He noticed that the provisions were collected by “a single rat, nearly grey” who “came out & took into the hole every piece,” apparently to distribute the goodies to his fellow rodents. Meigs admiringly remarked that there “was no noise whatsoever among them,” which he took to mean “that they eat in peace & divide fairly.”

Today, this sort of sensitivity to rat welfare strikes one as bizarre. It was equally unusual in the 1830s, when animals were valued primarily in terms of their usefulness to humans, as sources of food, labor, scientific data, entertainment, and even companionship and emotional support.

The New York rat was none of these. In the 1830s, rats did not yet elicit the intense fear and loathing that came from understanding their role in the spread of infectious diseases. Nonetheless, rats were heartily disliked. As the naturalist John James Audubon wrote, the “Norway rat,” “quite abundant in New York,” was “the most prolific and destructive little quadruped about the residences of man.”

Destroyers of crops and consummate thieves, rats, Audubon reported, were known to attack sleeping humans, especially little children. “Pugnacious,” “fierce, and “voracious,” they happily killed “each other,” the “weak ones devoured by the stronger.” They were not even “an American species,” but rather alien invaders brought “from Asia to Europe” and later, around 1775, to the United States. The fact that the animal had “a rough and not an inviting appearance” did nothing to improve its reputation. In 1839, Audubon received a permission to “to shoot rats at the Battery,” thus gaining an opportunity to exact revenge on critters that, back in 1812, had destroyed a box of his drawings.

In short, there was nothing to like about a rat. Why, then, would anyone—save perhaps a prisoner in solitary confinement or a particularly fanatical crusader for animal welfare—try to make friends with rats?

John James Audubon’s Brown or Norway Rat, from The Quadrupeds of North America (New York: Published by V.G. Audubon, 1851), vol. 2, plate 54. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Meigs, who, by his own admission, was constitutionally unable to hurt an animal, was no wild-eyed zealot, sad loner, or naïve dreamer. His diaries reveal a busy professional who served as a judge in one of the city courts, ran a successful law practice, and sat on the boards of New York’s most prominent institutions—including the American Institute, the Farmers’ Club, and the Washington Monument of New York. He was a happily married man who adored his wife of 32 years, loved his five children, and rejoiced in his two newborn grandchildren.

Neither was Meigs one to commune with nature in the woods. A consummate urbanite, he fully enjoyed everything that New York City had to offer—not only dinners at Delmonico’s, balls at City Hall, and museums and theaters, but also New York urban fauna.

Meigs, however, refused to judge animals by the standard of their usefulness to man. In addition to an impressive array of dogs and cats, his bustling household included an old blind horse. Meigs rescued the horse after its previous owner had left it to drown in a river and put him up to “give him a chance for another summer.”

On another occasion, Meigs was delighted to discover that a cricket had moved into his study. When, he wrote, “my Little Cricket” fell silent, he “set him a-going by some few notes of Piano in alto & by whistle,” observing that the cricket was “inclined to sing in accompaniment slow or quick.”

His military and political career led Meigs to question whether mankind was in fact the pinnacle of God’s creation. He found his lifelong experience with the justice system particularly galling, staffed as it was with “paid judges” beholden to “the will of a dominant party.” Apparently, the rational, polite, and fair brown rats presented a stark contrast to some humans Meigs knew who lived not only “without hearts” but also as though they were “not entitled to heads!”

Olga Tsapina is the Norris Foundation Curator of American History at The Huntington.