The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

George Washington, a Letter, and a Runaway Slave

Posted on Wed., March 21, 2018 by

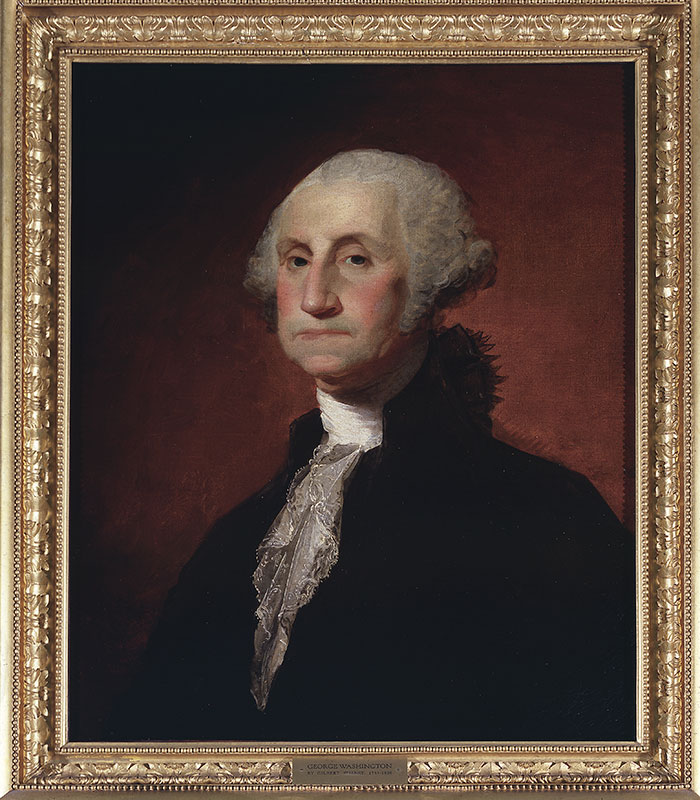

Gilbert Stuart, George Washington, 1797, oil on canvas, 28 1/2 x 23 5/8 in. (72.4 x 60 cm.)

frame: 35 1/4 x 30 5/16 x 3 in. (89.5 x 77 x 7.6 cm.). Gift of Mrs. Alexander Baring. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

On August 26, 1852, Charles Sumner (1811–1874), the junior Senator from Massachusetts, took the floor of the United States Senate to deliver a major speech against slavery. For three hours, Sumner blasted slavery as a barbaric custom that was an affront to the law of God, the foundational principles of the Republic, and the original intent of the Founding Fathers. The latter point was rather tricky to argue considering that several of the Founding Fathers had owned slaves. Sumner got around this obstacle by painting the Revolutionary generation, epitomized by George Washington, as unwilling inheritors of this poisonous legacy from the colonial past.

At this point in his speech, Sumner triumphantly held up an old letter, dating from 1796 and written by George Washington himself, that had “never before seen the light.” Addressed to Joseph Whipple, the collector of the customs in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, the letter asked Whipple to help recover a fugitive slave who had worked for Martha Washington.

Sumner pointed to Washington’s words that he was “well-disposed” to the abolition of slavery and that the runaway should not “be forcibly removed.” In the end, according to Sumner, the “fugitive was never returned, but lived in freedom to a good old age, down to a very recent day, a monument of the just forbearance of him who we aptly call Father of his Country.”

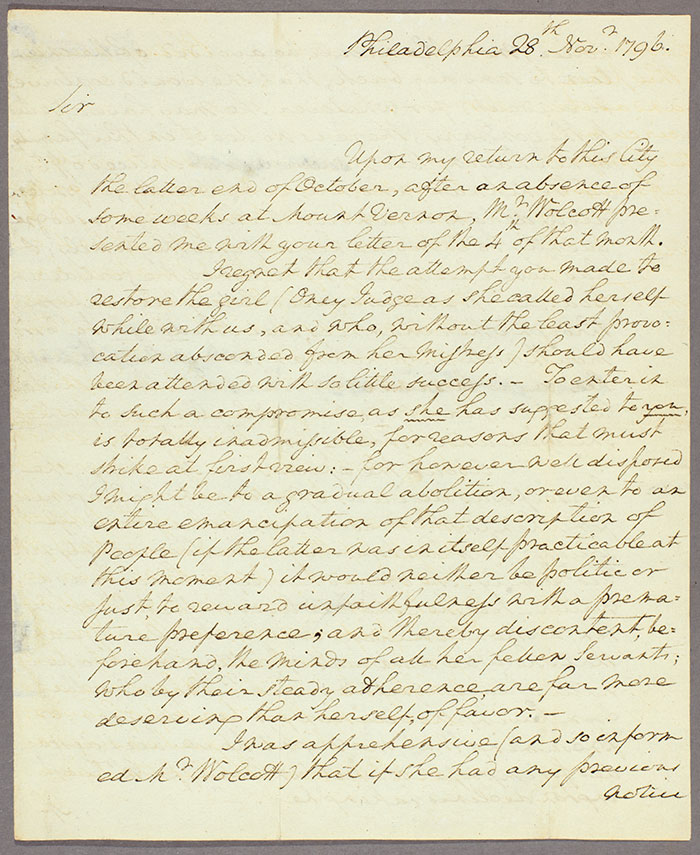

George Washington’s letter to Joseph Whipple regarding the runaway slave Ona Maria Judge, Nov. 28, 1796. In the second paragraph, Washington writes: “I regret that the attempt you made to restore the girl (Oney Judge as she called herself while with us, and who, without the least provocation absconded from her Mistress) should have been attended with so little success. To enter into such a compromise, as she has suggested to you, is totally inadmissible, for reasons that must strike at first view: for however well disposed I might be to a gradual abolition, or even to an entire emancipation of that description of People (if the latter was in itself practicable at this Moment) it would neither be politic or just, to reward unfaithfulness with a premature preference; and thereby discontent, beforehand, the minds of all her fellow Servants; who by their steady adherence, are far more deserving than herself, of favor.” The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

What a nice story. Unfortunately, it is also largely untrue. Washington’s letter, along with Whipple’s reply, now reside at The Huntington. They came to San Marino in 1960, after the Library acquired a collection of papers from the extended family of Reverend Charles Russel Lowell (1782–1861), a Boston Unitarian minister, anti-slavery preacher, and a relative of Whipple’s. Washington’s letter is indeed quite revealing, although mostly not in the way Sumner spins it.

The slave’s name was Ona (or Oney) Maria Judge, the subject of a recent book by Erica Dunbar, Never Caught: The Washingtons’ Relentless Pursuit of Their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge. A personal maid and “property” of Martha Washington’s, Ona Judge ran away from the president’s house in Philadelphia on May 21, 1796. Two days later, the president’s chief of staff placed an advertisement in two newspapers, offering a handsome reward for her return. It was too late: Judge had been able to board a ship that carried her to Portsmouth.

When Washington found out about Judge’s whereabouts, he asked his Secretary of the Treasury, John Oliver Wolcott, to help him return the young woman to Virginia in a discreet and speedy manner. Wolcott contacted Whipple, his subordinate, who duly arranged to meet Judge under the pretense of interviewing her for a position as a domestic servant. Wolcott forwarded Whipple’s report to the president.

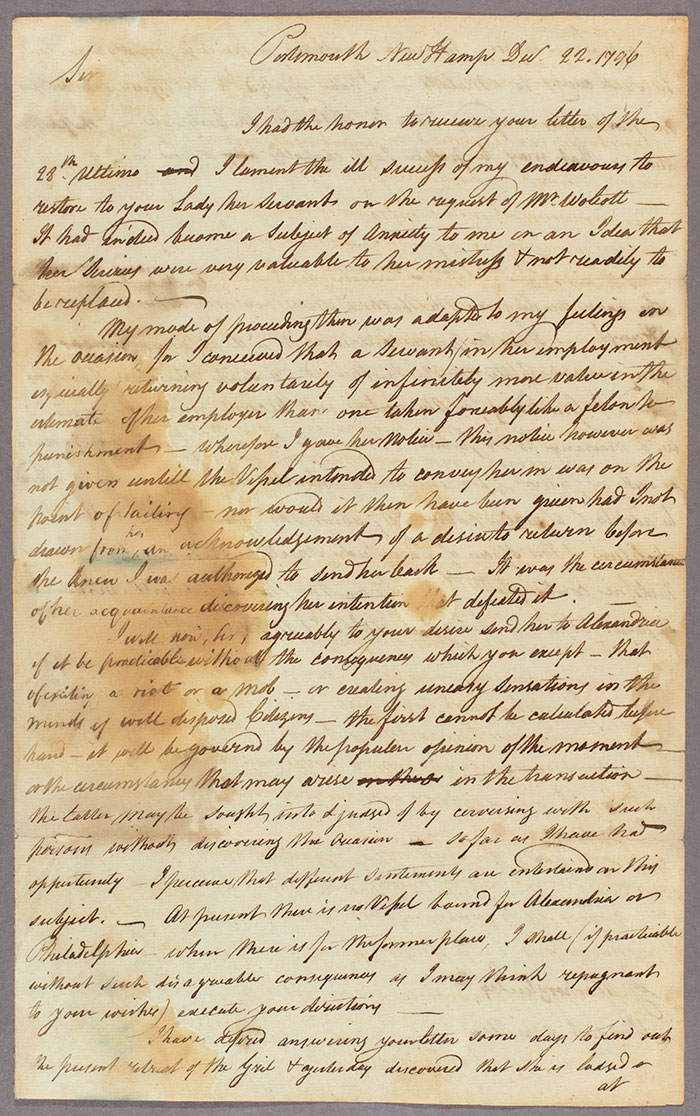

Letter from Joseph Whipple to George Washington, Dec. 22, 1796. In his second sentence, Whipple writes: “I sincerely Lament the ill success of my endeavours to restore to your Lady her servant on the request of Mr Wolcott—It had indeed become a subject of Anxiety to me on an Idea that her services were very valuable to her mistress and not readily to be replaced.” The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Washington’s letter of November 28, 1796, is a response to Whipple’s report. When read in its entirety, the letter doesn’t speak to his conviction regarding the abolition of slavery. Rather, it has the combative and aggrieved tone of a slaveholder smarting from the loss of his wife’s human property.

Washington had little appreciation for Whipple’s report that Judge had decided to run away because of her “thirst for compleat freedom.” Nor did Washington favorably view Judge’s “willingness to return & to serve with fidelity during the lives of the President & his Lady if she could be freed on their decease, should she outlive them.”

The president was having none of it. “To enter into such a compromise, as she has suggested to you, is totally inadmissible,” writes the president. Moreover, to concede to Judge’s proposal would be tantamount to rewarding “unfaithfulness with a premature preference,” which would be unfair to “her fellow Servants; who by their steady adherence, are far more deserving than herself, of favor.”

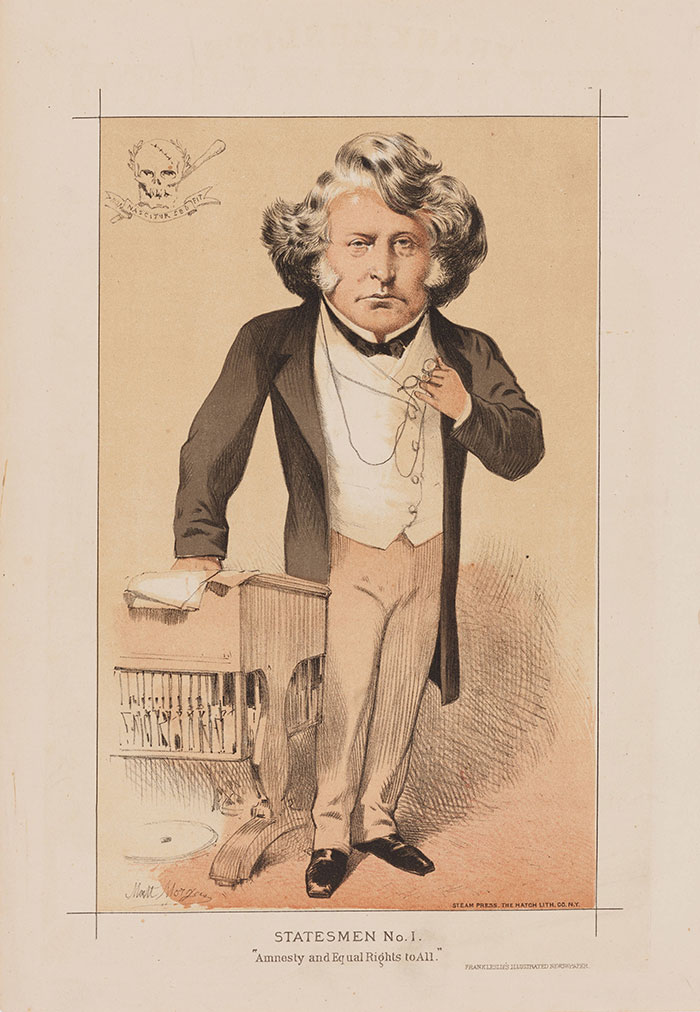

A caricature of the Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner (1811–1874), titled Statesmen No. 1. “Amnesty and equal rights to all.” On August 26, 1852, Sumner held up Washington’s letter about Ona Judge during his Senate speech against slavery and interpreted it in a way that bolstered his argument at the expense of strict historical accuracy. Jay T. Last Collection of Graphic Arts and Social History. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

And here was the rub. The Father of the Nation, in his widely popular “Farewell Address,” published just two months earlier, had solemnly presaged that the blessing of liberty would secure “the happiness of the people of these States.” Clearly, he must have excluded slaves from this happy future. For “that description of People,” as Washington refers to slaves in his letter to Whipple, liberty was a “favor” to be granted or withheld by the master.

This sentiment was hardly peculiar to the South. In 1779, a group of 19 New Hampshire slaves petitioned to the state legislature for their freedom, only to be told that the conditions were “not ripe for a determination in this matter.” The legislature in the Granite State, which became Ona Judge’s home, postponed the decision until “a more convenient opportunity.”

That day finally arrived . . . but not until 2013, when the governor of New Hampshire signed a bill into law that posthumously granted the slaves their freedom.

Olga Tsapina is the Norris Foundation Curator of American Historical Manuscripts at The Huntington.