The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Susan B. Anthony and the Price of Suffrage

Posted on Thu., Nov. 3, 2016 by

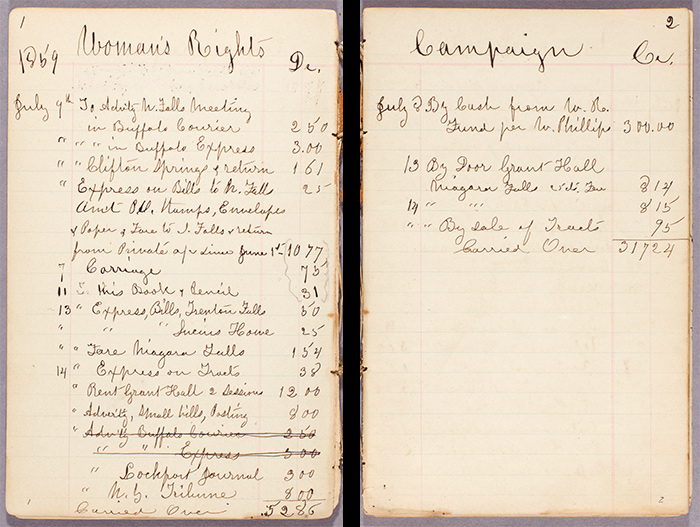

Two pages from Susan B. Anthony account book, April 17, 1858–July 27, 1860. In the spring of 1859, Anthony was engaged in preparation for the 9th Woman’s Rights Convention in New York City. The convention opened on May 12, 1859, at the Mozart Hall. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The sight of an old account ledger doesn’t generally excite many people—aside from historians and forensic accountants. But a ledger that once belonged to the famous American feminist and social reformer Susan B. Anthony (1820–1906) has wider appeal because its entries reveal priceless information about efforts to secure women’s voting rights.

The Huntington acquired such a ledger this year from the Art Directors Guild in Studio City. The cover of the small, tattered, and simple manuscript reads: “S.B. Anthony Rochester N.Y. 1859.”

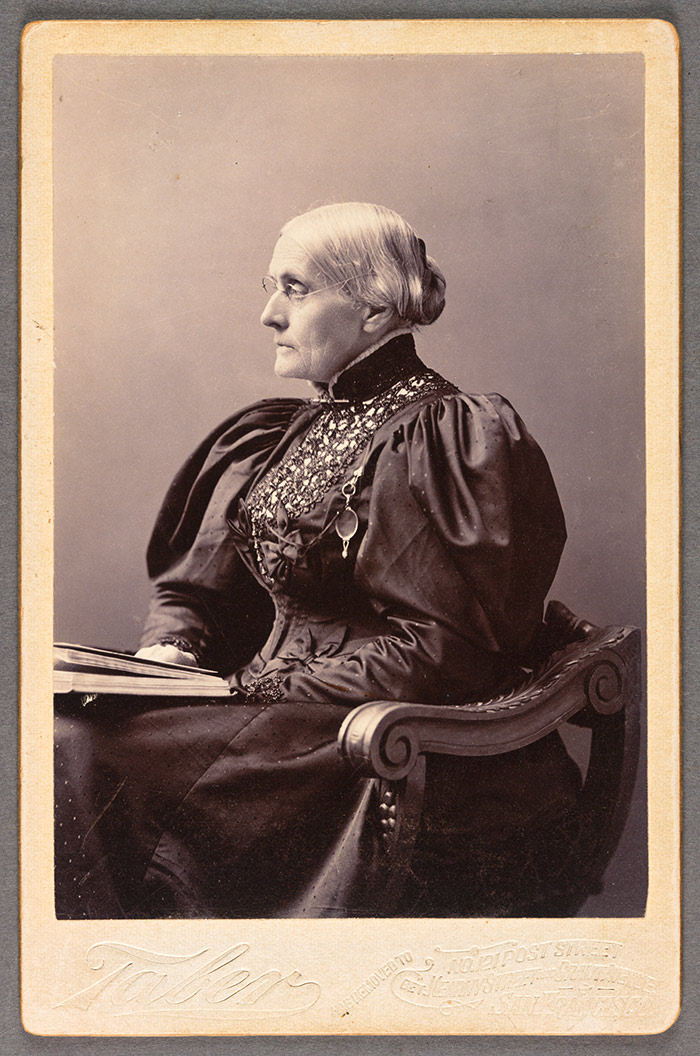

Anthony, who started out as a schoolteacher, is best remembered for her advocacy of women’s suffrage, which became enshrined as the law of the land when the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified in 1920. Popularly known as the “Susan B. Anthony Amendment,” it proclaimed: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

Portrait of Susan B. Anthony, 1895, Taber Photographic Co. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

First introduced in 1878, the Anthony Amendment would require 42 years of campaigning in order to garner the constitutionally mandated two-thirds vote in both houses of Congress. Sadly, it passed 14 years after Anthony’s death. It would take another 44 years to get a woman to appear on the presidential ballot of a major political party—that occurred in 1964 with Maine Republican Margaret Chase Smith. (And it would take 52 more years for Hillary Clinton to become, in 2016, the first woman to be nominated for president.)

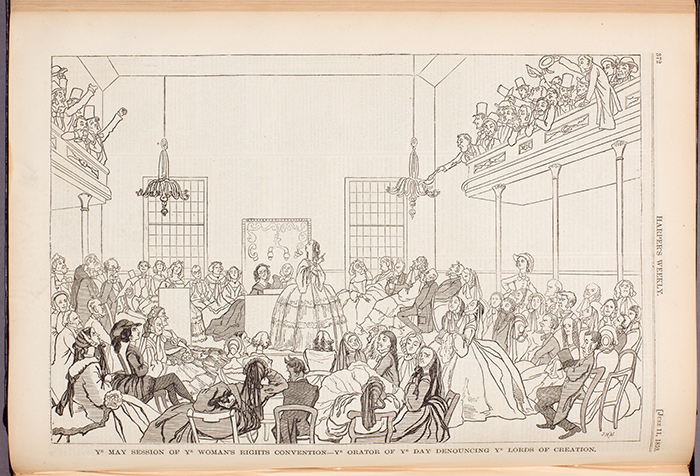

The Huntington’s Anthony ledger documents the financial realities of prolonged social welfare campaigning. There were venues to be rented, newspaper advertisements to be placed; books and pamphlets to be printed; speakers to be paid; and stenographers, ticket takers, and “police door tenders” to be hired. The latter were important: the proceedings at women’s rights meetings in the mid-19th century were frequently and violently disrupted. As one New York newspaper put it, “women have no rights in public to which men are bound,” and so paying for protection was a must.

Anthony also recorded entries for hotel bills, railroad and riverboat tickets, carriage fares, and even the price of “this book and pencil”—the ledger itself and the implement she used to record each credit and debit. Reading the entries, you can follow Anthony and her traveling companions, Antoinette Brown Blackwell and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, as they journeyed to New York City to preside over national conventions, gave public lectures in various New York towns, and spoke at the annual teachers’ meetings in Poughkeepsie and Syracuse.

“Ye May Session of Ye Woman’s Rights Convention—Ye Orator of Ye Day Denouncing Ye Lords of Creation,” Harper’s Weekly, June 11, 1859. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Fundraising became particularly challenging in the wake of the 1857 Panic. In 1858, Francis Jackson made a gift of $5,000 (the equivalent of roughly $135,000 in today’s money) to the cause, and a year later, Charles F. Hovey, a wealthy Boston merchant, donated 10 times as much. The main sources of revenue, however, were the funds raised from public events, subscriptions, and much smaller donations—$20 from Francis Jackson, $25 from Geritt Smith, $3 from Lucretia Mott. In December 1859, Anthony recorded a $1 cash donation received at a meeting commemorating John Brown, the abolitionist who had been executed on charges of treason, murder, and insurrection two weeks earlier.

There are also meticulous records of the proceeds from the admission to meetings and sales of lecture tickets and suffragist and abolitionist literature. All in all, Anthony ran a remarkably efficient campaign that paid for itself, with significant sums carried over.

We delight in criticizing the power of money in American politics today. It is instructive that, as Anthony’s little ledger shows, a successful civil rights movement requires not only heroism and sacrifice, but also the less glamorous and pedestrian labor of accounting.

Related content on Verso:

“I have been & gone & done it!!” (Nov. 5, 2013)

Olga Tsapina is the Norris Foundation Curator of American Historical Manuscripts at The Huntington.