The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Einstein’s Still Making Waves

Posted on Thu., March 10, 2016 by and

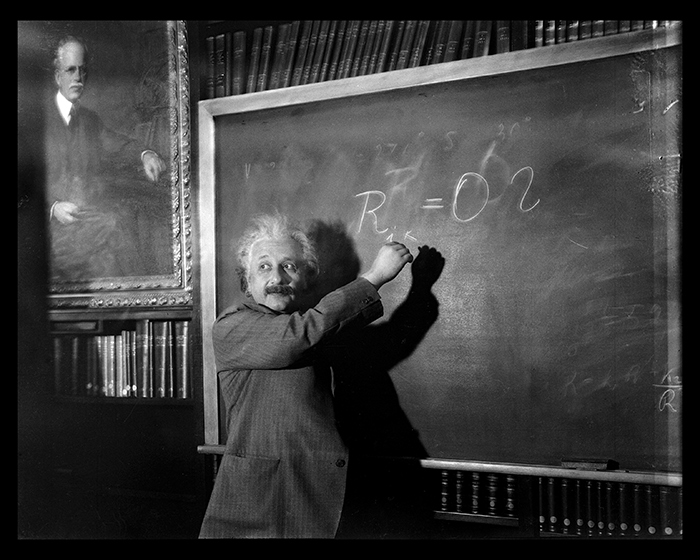

Albert Einstein at the blackboard during a talk, circa 1931, in the Mount Wilson Observatory's Hale Library, Pasadena, California. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Tomorrow The Huntington will cohost the second day of Caltech’s sixth biennial Francis Bacon Conference, “General Relativity at One Hundred.” The conference runs from March 10–12, with the first and third days taking place at Caltech. It will bring together physicists and scholars to explore topics ranging from the early history of general relativity to current projects, including gravitational wave detection. Talks will include a focus on last month’s announcement that scientists had found, for the first time, direct evidence of gravitational waves—hailed as one of greatest discoveries in the history of physics and something that Albert Einstein had predicted 100 years ago.

One of the key players in that story is Kip Thorne, Caltech’s Feynman Professor of Theoretical Physics, emeritus. Thorne will deliver a free public lecture, “100 Years of Relativity: From the Big Bang to Black Holes and Gravitational Waves,” at The Huntington’s Rothenberg Hall tomorrow at 7:30 p.m. He will explain the ideas underlying Einstein’s general theory of relativity—which describes space and time as warped by mass and energy—and will discuss discoveries made in the theory's wake.

“Humans are embarking on a marvelous new quest: exploring the warped side of the universe—objects and phenomena that are made from warped space-time. Colliding black holes and gravitational waves are our first beautiful examples,” said Thorne in a press release issued by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory, or LIGO, where the discovery was made.

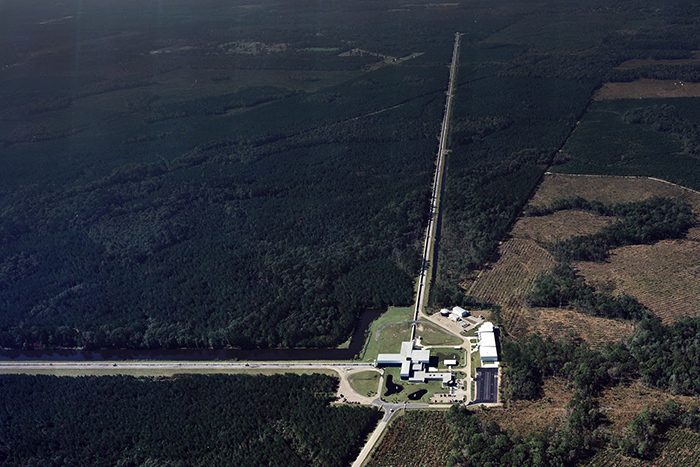

Aerial shot of the LIGO Livingston Lab, located in Louisiana. Although considered a single observatory, LIGO comprises four facilities across the United States: two gravitational wave detectors and two university research centers. The detectors, separated by 1,865 miles, are located in Livingston, Louisiana, and Hanford, Washington. The two primary research centers are located at Caltech and MIT. Photo courtesy of LIGO.

A team of scientists from LIGO announced in February that they had recorded gravitational waves generated by a pair of massive black holes that collided and merged about 1.3 billion years ago, releasing an enormous amount of energy. LIGO’s twin gravitational wave detectors, one in the state of Washington and the other in Louisiana, detected evidence of that energy in the form of gravitational waves on Sept. 14, 2015.

Founded by Thorne, Rainer Weiss (professor of physics, emeritus, from MIT), and Ronald Drever (professor of physics, emeritus, from Caltech), LIGO achieved these spectacular results through decades of work conducted by hundreds of scientists and engineers, led from 1997 to 2005 by LIGO’s director Barry Barish, Caltech’s Ronald and Maxine Linde Professor of Physics, emeritus. He will also speak during tomorrow’s conference proceedings at The Huntington.

The Huntington and Caltech are fitting places for celebrating Einstein’s legacy. One of the gems in The Huntington’s history of science collection is a 1913 letter from Einstein to solar astronomer George Ellery Hale, who founded the Carnegie Foundation’s Mt. Wilson Observatory and was instrumental in the creation of Caltech and The Huntington. In the letter, Einstein inquires whether it would be possible to measure starlight bending around the sun during the day.

Banquet given by Caltech associates in honor of Albert Einstein on Feb. 15, 1931. Sitting (from left to right): Robert Millikan, Einstein, Albert Michelson (these first three were Nobel laureates), and William Wallace Campbell. Standing (left to right): Charles St. John, Walter Mayer, Edwin Hubble, William Nunro, Richard Tolman, Allan Balch, Walter Adams, and Russell Ballard. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Einstein interacted with physicists and astronomers at Caltech over three winter terms in the early 1930s. At Mt. Wilson, Einstein peered into what were the most powerful optical telescopes in the world at the time and saw exquisite equipment designed to explore the nature of sunspots, the bending of light, and the size of the universe—all topics that he had addressed in his earlier work.

Today Caltech is home to the Einstein Papers Project, whose international scholars and support staff collect, transcribe, annotate, and publish The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein. Published volumes draw upon Einstein’s personal papers held at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s Albert Einstein Archives and more than 40,000 additional Einstein and Einstein-related documents discovered by the project’s researchers since the 1980s. The Collected Papers of Albert Einsteinis providing the first complete picture of Einstein’s massive written legacy.

Einstein’s genius continues to inform our comprehension of the physical universe. When it comes to cosmology, he’s still making waves.

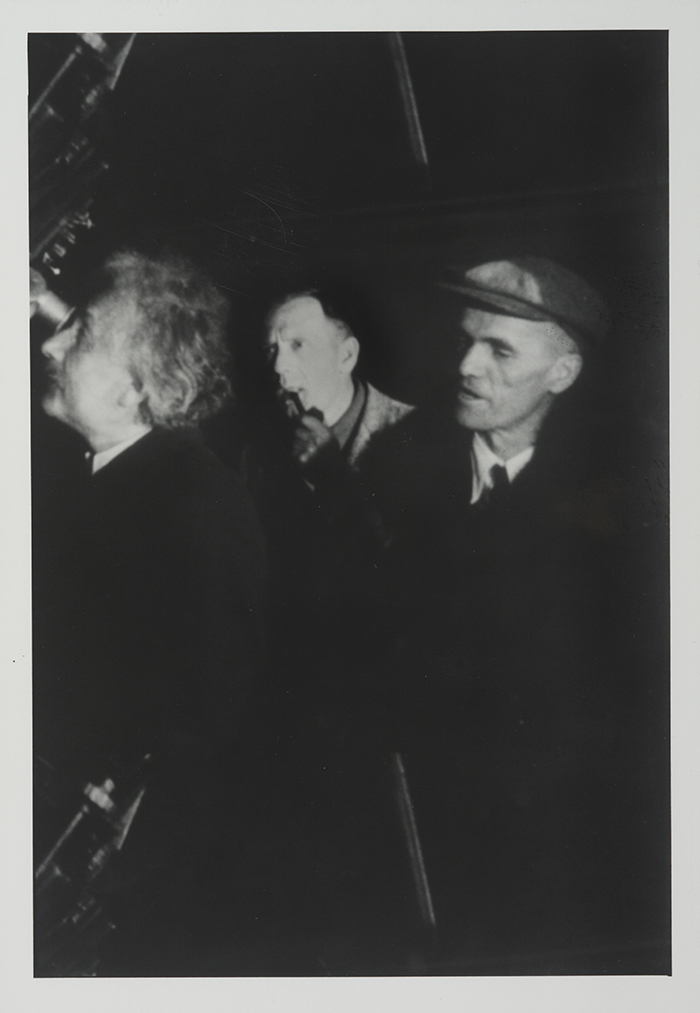

From left to right, Albert Einstein and astronomers Edwin Hubble and Walter Adams at the Mt. Wilson observatory in 1931. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

For more information about “General Relativity at One Hundred,” go to Caltech’s conference website. All sessions are free and open to the public.

A concurrent exhibition documenting how Einstein formulated his theory of general relativity will be on view at The Huntington on March 10 from noon until 4:30 p.m. and on March 11 from 9 a.m. to 7:30 p.m. in Roger’s classroom, located in the June and Merle Banta Education Center next to Rothenberg Hall. The exhibition comprises facsimiles of Einstein’s manuscripts, letters to colleagues, photographs, and books that are housed at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Related content on Verso:

Einstein and the Astronomers (March 13, 2015)

Diana L. Kormos-Buchwald is professor of history and director of the Einstein Papers Project at Caltech.

Kevin Durkin is the editor of Verso and managing editor in the office of communications and marketing at The Huntington.