The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Einstein and the Astronomers

Posted on Fri., March 13, 2015 by

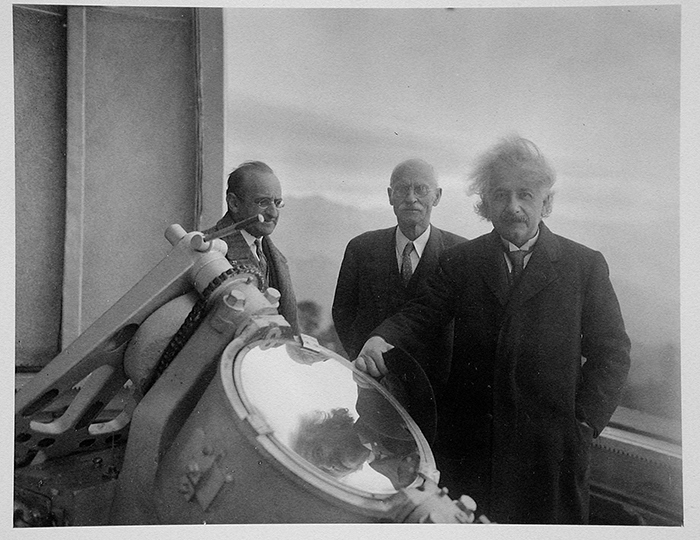

Albert Einstein (right) at the top of the 150-foot solar tower at the Mount Wilson Observatory, with solar physicist Charles St. John (middle) and mathematician Walther Mayer (left). Jan. 29, 1931. The Observatories of the Carnegie Institution for Science Collection at The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

On the eve of Albert Einstein’s 136th birthday on March 14, we invite you to consider a letter Einstein wrote in 1913 to renowned solar astronomer George Ellery Hale (1868-1938)—a letter reminding us of the dance between theory and experiment.

In June 1911, several years before Einstein worked out the final details of his general theory of relativity, he completed a paper titled “On the Influence of Gravitation on the Propagation of Light.” In this work, he theorized that the gravitational field of the sun was powerful enough to cause an observable bending of starlight—a deflection that could be measured during a total solar eclipse. Einstein predicted that the position of a star near the sun would appear to have shifted from its normal position by an angle of somewhat less than one second of arc, or less than 1/3600 of a degree.

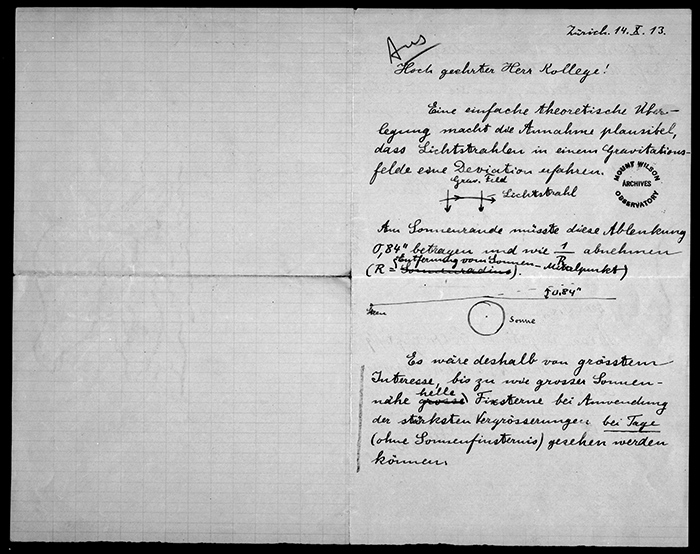

In his letter to George Ellery Hale, Einstein illustrates starlight being deflected by the gravity of the sun. Oct. 14, 1913. The Observatories of the Carnegie Institution for Science Collection at The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Over the ensuing months and years, Einstein corresponded with several astronomers to draw attention to the importance of his theory and solicit their help in refining his predictions through astronomical observation. One person he wrote to was Hale, founder of the Mount Wilson Observatory, which was home at the time to the world’s largest operational telescope. As a solar physicist, Hale would become best known for his discovery of magnetic fields in sunspots, but he also possessed remarkable terrestrial influence, helping to found both The Huntington and the California Institute of Technology. Einstein’s letter is one of the gems among Hale’s papers at The Huntington.

In his 1913 letter to Hale, Einstein asked (in his native German) if it would be possible to test his prediction without waiting for an eclipse. Hale wrote back that an eclipse was necessary. Sunlight would otherwise obscure stars that appeared close to the sun.

Undeterred, Einstein continued to seek help from colleagues. One of his most frequent correspondents was German astronomer Erwin Finley-Freundlich, who planned an expedition to the Crimea in 1914 to observe an eclipse and test Einstein’s prediction. Due to the outbreak of World War I, the members of the expedition were taken into custody and their equipment was confiscated. This sad turn of events proved to be something of a boon for Einstein, giving him more time to complete his general theory of relativity and revise his calculation.

Indeed, in 1915, Einstein significantly altered his prediction, calculating that the angle of deflection would be twice as large as he’d originally thought.

Einstein peers into the solar telescope’s eyepiece, with Mayer in the background. Mount Wilson Observatory. Jan. 29, 1931. The Observatories of the Carnegie Institution for Science Collection at The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Finally, on May 29, 1919, British astronomer Arthur Eddington provided the first confirmation of Einstein’s general theory of relativity by measuring the apparent displacement of stars during a solar eclipse that he observed on the island of Principe, located off the west coast of Africa. The publication of Eddington’s results the following year made Einstein world famous.

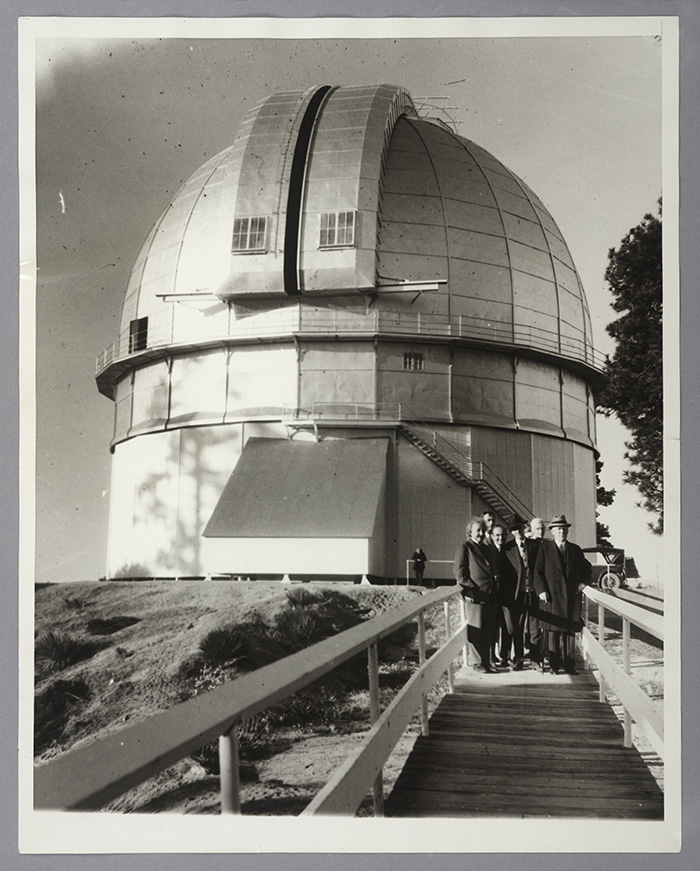

Einstein would make his first of several visits to Mount Wilson in 1931 while serving as a research associate at the California Institute of Technology. The Huntington possesses numerous photographs of Einstein visiting Mount Wilson but none of Hale and Einstein together.

Instead, we see a smiling Einstein in the glare of the California sun with the astronomers Edwin Hubble, Walter Adams, and William Campbell, among others—captured for a moment of levity in space and time.

Left to right: Albert Einstein, Edwin Hubble, Walther Mayer, Walter S. Adams, Arthur S. King, and William W. Campbell pose in front of the 100-inch telescope dome at Mount Wilson Observatory. Jan. 29, 1931. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

A facsimile of the letter from Einstein to Hale is on display in the astronomy section of The Huntington’s permanent exhibition “Beautiful Science: Ideas that Changed the World.”

Kevin Durkin is editor of Verso and managing editor for the office of communications and marketing at The Huntington.