The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Come What Will, Part 2

Posted on Tue., Nov. 6, 2012 by

Today we bring you the second part of a post by Olga Tsapina, the Norris Foundation Curator of American Historical Manuscripts and curator of the current exhibition “A Just Cause: Voices of the American Civil War.” Continuing her post from yesterday, she recounts the final dramatic months of Abraham Lincoln’s reelection campaign in 1864.

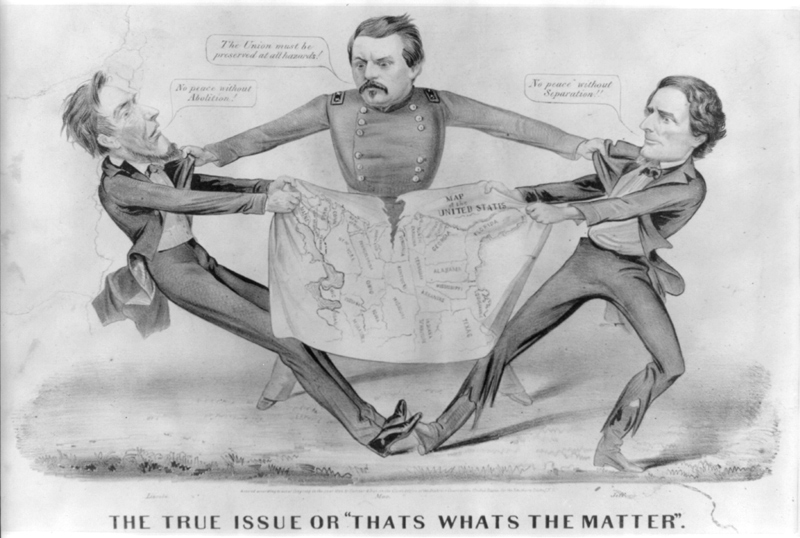

Currier & Ives, “The True Issue or ‘That’s What’s the Matter,’ ” ca. 1864. Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

By late summer of 1864, Lincoln had come to the disheartening conclusion that his presidency was doomed. On Aug. 22, he was informed that if the elections were held that day, he would lose New York, Pennsylvania, and his home state of Illinois. On the next day, he wrote a memorandum to his cabinet. “This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly probable that this administration will not be re-elected. Then it will be my duty to so co-operate with the president-elect, as to save the Union between the election and the inauguration; as he will have secured his election on such grounds that he can not possibly save it afterwards.” Lincoln then asked each member to sign the memo without reading it. Convinced that the Union could not be saved without killing slavery, the president committed his cabinet to ensuring that the abolition of slavery would be made permanent before the new, Democratic president took office.

Lincoln was correct in his assumptions about his challenger and old nemesis, George B. McClellan. The Democratic Party convention that met at the end of August in Chicago adopted a platform that minced no words in condemning the Lincoln administration for “four years of failure to restore the Union by the experiment of war,” which produced no result except blatant disregard for the Constitution and “public liberty and private right alike trodden down.” Street rallies were even more explicit: Henry Clay Dean of Iowa blasted Lincoln as “the usurper, traitor, and tyrant,” whose administrations had “failed! Failed! FAILED! FAILED!” The platform “explicitly” promised that the new administration would make “immediate efforts” to restore peace “on the basis of the Federal Union of the States,” with “the rights of the States unimpaired,” that is, with slavery intact.

However popular McClellan might have been, the peace plank in the Democratic Party platform was met with indignation in the North. Thomas Nast, a Harper’s Weekly caricaturist, captured this outrage in his editorial cartoon that depicted a defeated and maimed Union soldier submitting to a triumphant Jefferson Davis, who is treading contemptuously on the Union grave as a black Union soldier is being dragged away to slavery.

Thomas Nast, “Compromise with the South. Dedicated to the Chicago Convention.” From Harper’s Weekly, Sept. 4, 1864. Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

On Sept. 4, the very same day when this image was published, at 5:30 p.m., the War Department received a telegram from Sherman: “Atlanta is ours, and fairly won.” Sherman’s victory made a mockery of the Democrats’ accusations of failure and doomed all talks of immediate peace.

The fall campaign was fierce. The Democratic press blasted Lincoln for misleading the nation into an unconstitutional abolitionist crusade, endangering the Union, violating civil rights, ruining the nation’s finances, and promoting a radical racial agenda.

The Lincoln campaign branded McClellan and his running mate, George H. Pendleton, as traitors whose victory would consign the free North to the domination of the slaveholding South.

Despite the Union victories and the unprecedented increase in federal control over the election process, there was a palpable uncertainty about the results.

The incumbent and the challenger carefully watched the returns from the October 11 state elections in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Indiana. The elections in these “bellwether” states were believed to predict the outcome of the general elections. The Union Party carried all three, although a rather slim Union majority in Indiana prompted accusations of electoral fraud.

One measure of the public opinion was betting on the elections results. The odds moved in favor of Lincoln’s reelection only in the last week before Election Day.

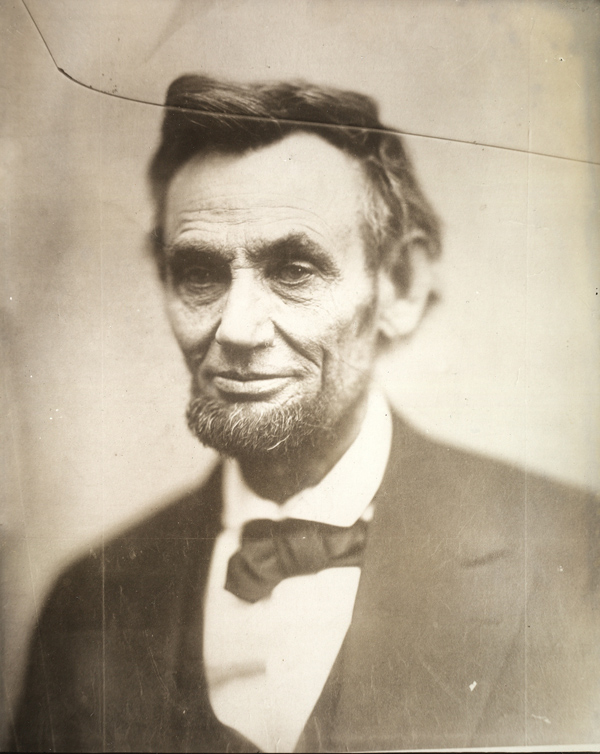

This photograph of Abraham Lincoln by Alexander Gardner, taken on Feb. 5, 1865, was one of the last photographs ever taken of the president. Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

On Election Day Lincoln had gained 55 percent of the popular vote and won 212 electoral votes, to McClellan’s 21. (Besides his home state of New Jersey, “the little Mac” carried only Kentucky and Delaware). Lincoln became the first president to win a second term in office since Andrew Jackson in 1832.

Two and a half months later, on Jan. 31, 1865, the House passed the resolution adopting the 13th Amendment. A month after his second inauguration, Richmond fell, and on April 9, Robert E. Lee signed the articles of surrender. Two days later, as Abraham Lincoln addressed the jubilant crowd at the White House, one spectator, John Wilkes Booth, muttered: “That is the last speech he will ever make.”

Related content on Verso:

Come What Will, Part 1 (Nov. 5, 2012)

Voices on the Civil War (Oct. 12, 2012)

Olga Tsapina is the Norris Foundation Curator of American Historical Manuscripts at The Huntington.