The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Come What Will, Part 1

Posted on Mon., Nov. 5, 2012 by

Today and tomorrow we bring you a two-part piece by Olga Tsapina, the Norris Foundation Curator of American Historical Manuscripts and curator of the current exhibition “A Just Cause: Voices of the American Civil War.” In these posts she recounts the final dramatic months of Abraham Lincoln’s reelection campaign in 1864.

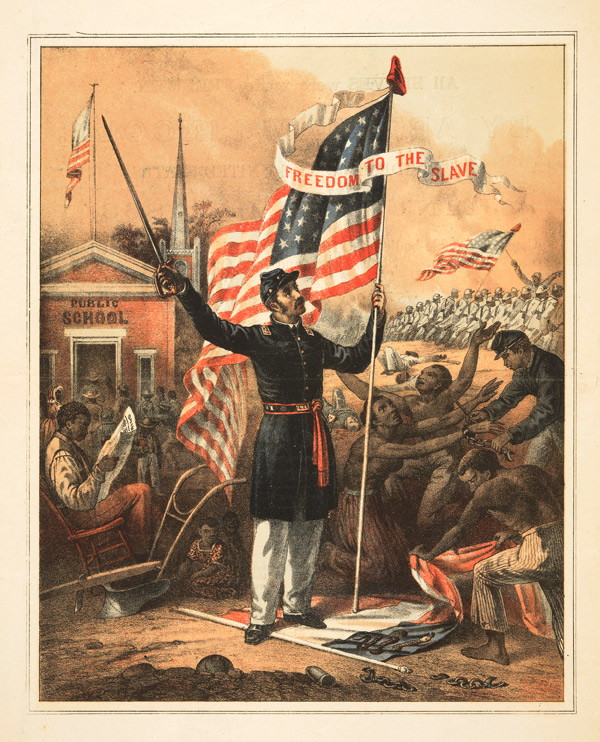

Freedom to the Slave, recruitment handbill, chromolithograph, 1863. Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

“The world shall know that I will keep my faith to friends & enemies, come what will.”

—Abraham Lincoln, Aug. 19, 1864

Abraham Lincoln had a reason to be optimistic at the dawn of the election year of 1864. The Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg seemed to herald a speedy end to the Civil War.

Lincoln’s Republican Party had refashioned itself into the Union Party, shedding the taint of divisive radicalism and reaching out to the pro-war Democrats. The Union Party, through its highly efficient network of the Union Leagues, positioned itself as the only champion of one, united America that had transcended the dreaded “spirit of party.” The anti-war Democratic opposition that had come to be known as the Copperheads seemed to be in disarray.

The cause of emancipation, which just a year earlier was denounced as dangerous radicalism, became an integral part of the Union patriotism. More and more Northerners had come to see slavery as the gravest threat to national unity and its eradication as vital to the preservation of a nation “conceived in liberty.”

A plan that would amend the Constitution to eradicate slavery, once rejected as a gross distortion of the legacy of the Founding Fathers, was gaining mainstream support. In January 1864, the Senate Judiciary Committee took up the discussion of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, and on April 8, the Amendment was passed in the Senate. (It was immediately blocked in the House, where 65 out of 68 Democratic congressmen voted against it.)

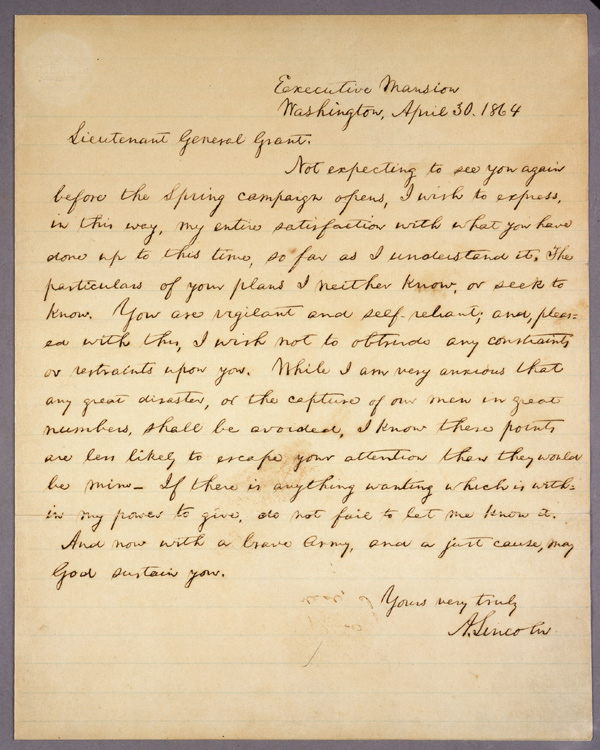

A week later, Ulysses S. Grant, who had devised an ambitious campaign aimed at destruction of the Confederate armies in Virginia, Alabama, and Georgia, received the rank of lieutenant general, which only George Washington had borne before. On April 30, the president bid farewell to Grant: “And now with a brave Army, and a just cause, may God sustain you.”

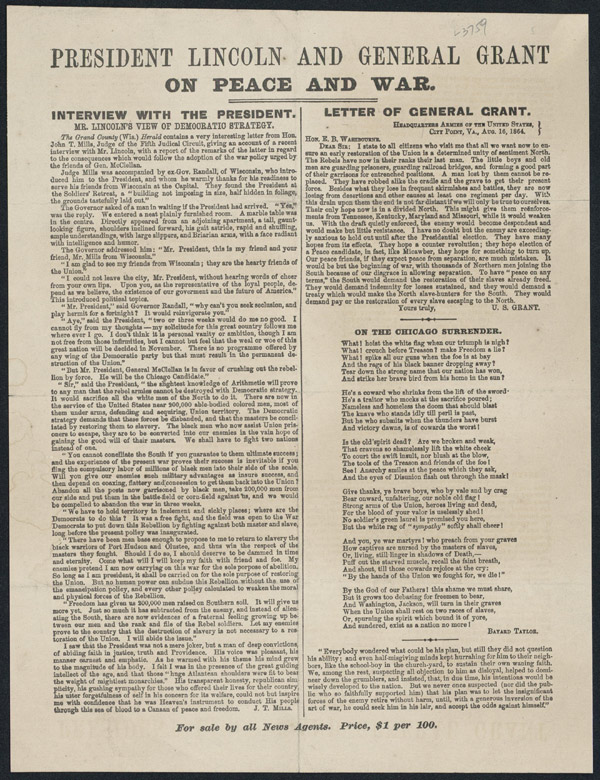

Printed leaftlet with Lincoln’s interview with John T. Mills. Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Alfred Whital Stern Collection of Lincolniana.

On June 7, the Union Party convention at Baltimore nominated Abraham Lincoln, with a Southerner, Andrew Johnson of Tennessee, as his running mate. The convention also adopted the platform that demanded the unconditional surrender of the Confederacy and “utter and complete extirpation” of slavery. Lincoln’s Union Party became the first mainstream party to campaign on the abolition of slavery.

Yet by mid-July, optimism had evaporated. Sherman’s army was bogged down in Georgia, unable to take Atlanta. Grant’s Overland campaign stalled at Petersburg, Va., having lost some 64,000 men in a mere two months. On July 11, the Confederate Cavalry showed up at the very gates of Washington, D.C.

As the North appeared about to buckle under the enormous weight of the war, the calls for peace grew more and more persistent. The Copperheads grew in strength and their attacks on the Lincoln administration became louder.

By mid-August, Lincoln had become a liability even to some members of his own party. His long-time supporter Horace Greeley was worried that the President was “already beaten” and could not be reelected. The president was pressured to sue for peace “on the sole condition of acknowledging the supremacy of the constitution.” That meant abandoning any attempts to abolish slavery.

Lincoln refused. On Aug. 19, he sat for an interview with Joseph Trotter Mills (1811–1897), a Wisconsin judge. The president firmly rejected any suggestions that he might drop emancipation from his program and “return to slavery the black warriors” of the Union Army. “I should be damned in time & in eternity for so doing. The world shall know that I will keep my faith to friends & enemies, come what will.”

Abraham Lincoln, letter to Ulysses S. Grant, April 30, 1864. Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Tomorrow we will post the second part of “Come What Will.”

Related content on Verso:

Come What Will, Part 2 (Nov. 6, 2012)

Voices on the Civil War (Oct. 12, 2012)

Olga Tsapina is the Norris Foundation Curator of American Historical Manuscripts at The Huntington.