The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

LECTURES | Reports on the Death of Letter Writing Are Greatly Exaggerated

Posted on Tue., Dec. 6, 2011 by

Margaret Cocks, later Margaret Smith, 1787, by Richard Cosway. © The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

When was the last time you wrote a real, honest-to-goodness letter? In the age of e-mail and texting, it is only natural to assume that the glorious age of letter writing was far superior to, say, the confines of 140 characters on Twitter.

But while we might indeed write fewer letters today, we might also want to reconsider our assumptions about letter writing before the age of the computer, or even before the advent of the postal service.

"Most letters from the 16th through the 19th centuries were quite short," explains Peter Stallybrass, professor of English at the University of Pennsylvania and the R. Stanton Avery Distinguished Fellow at The Huntington for 2011–12. "A typical letter writer tried to write as little as possible by increasing the size of his or her handwriting or, most commonly, by folding the paper once or twice to create a very small space to write in." The rest of the sheet would remain blank.

On Wednesday night, Dec. 7, Stallybrass will deliver a public lecture titled "What Is a Letter?" In it, he'll explain how writers from the 16th century onward used a number of techniques that might be difficult to decipher today but were well known conventions at the time.

Mary Shelly (1797–1851), for example—the author of Frankenstein—once sent a letter to her dear friend Isabella Booth that was folded like a diamond, a clear symbol of abiding love and affection. Poet John Donne (1572–1631), who was imprisoned briefly following his scandalous marriage to Anne More, wrote a series of letters that he signed, "Yor LPS poor and repentant servant, John Donne." The abbreviation for "Your Lordship's" would be clearly understood by the reader of the letter, as would the mark of humility of the placement of the signature at the furthest possible distance from the end of the message in lower right corner of the page.

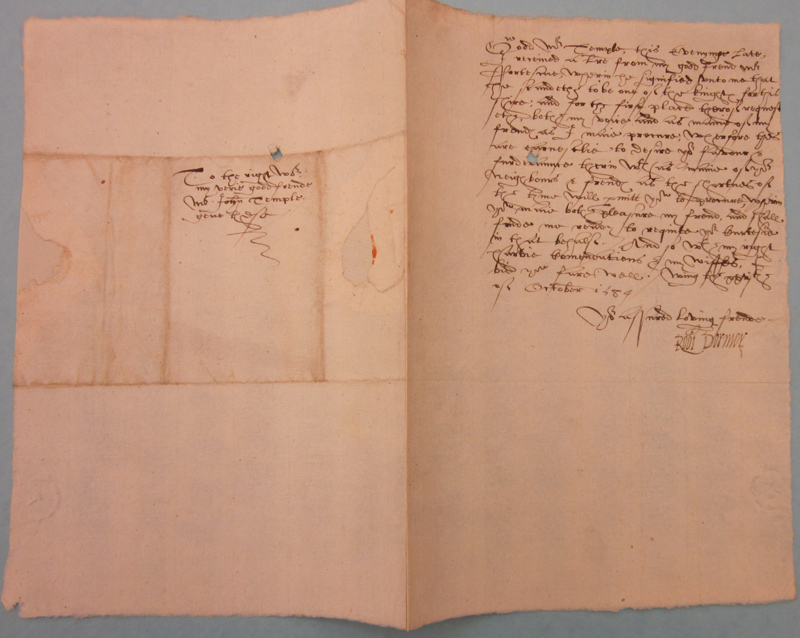

Letter from Robert Dormer, 1st Baron Dormer to John Temple, Oct. 27, 1584; from the Temple collection at The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. The Temples were a prominent family in Buckinghamshire, England.

These conventions—the folding, the large handwriting, the placement of the signature, the use of dashes—are lost on scholars who read only printed transcriptions of letters. Stallybrass says there is a revival of interest in appreciating the material text of letters, of seeing the creases in the paper and the variations in penmanship.

And Stallybrass is also quick to absolve all of us of any guilt over our use of modern equivalents of letter writing—e-mails, texts, Facebook posts—that is, as long as you turn off your cell phones when you attend the lecture.

The lecture takes place on Wed., Dec. 7, at 7:30 p.m. in Friends' Hall and is free and open to the public. No reservations required.

Peter Stallybrass is Walter H. and Leonore C. Annenberg Professor in the Humanities and Professor of English and of Comparative Literature and Literary Theory. You can listen to his 2010 lecture at The Huntington—What Is a Book?—on iTunes U.

Matt Stevens is editor of Huntington Frontiers magazine.