In the Back of God’s Elbow

Posted on Fri., Dec. 28, 2018 by

A collection of correspondence yields insight into the Seven Years' War

The South View of Oswego, on Lake Ontario, 1760. Despite this flattering depiction in the London Magazine (vol. 29, May 1760, page 232), Fort Oswego, in 1756, was in fact falling apart. It had no storehouses, no barracks, and no hospital.

On Nov. 13, 1756, James Grahame hastily scribbled a letter at his London residence. The note, addressed to William Mercer in Perth, Scotland, confirmed that Grahame’s friend and William’s brother, Col. James F. Mercer, was dead. He was killed on the morning of Aug. 14, 1756, struck “by a Cannonshot from the Enemy” as he rallied his men against the French at Fort Oswego, Britain’s northernmost outpost in America.

Mercer was just one of roughly 1 million fighting men who perished in the global conflict known today as the French and Indian or Seven Years’ War (1756–63)—a conflict that Winston Churchill dubbed the first world war. Most of these men now appear as mere ciphers in casualty reports, remembered only for their deaths, not their lives.

Mercer’s death was gruesome but mercifully quick: the French “Cannonshot” decapitated him. It also set off a chain of events that resulted in a major political crisis.

Mercer’s second-in-command was reportedly so unnerved that he immediately hoisted the white flag of surrender. The French commander, the Marquis de Montcalm, expecting a longer siege (the conventions of the time demanded at least three days), refused to recognize the surrender as honorable. Instead of leaving the fort to the beat of their own drums and with their colors flying, the British were rounded up as prisoners of war. As the disarmed men staggered out, they were attacked by the French-allied Native American warriors. And, before Montcalm managed to restore a semblance of order, some 30 men were dead. In London, the news of the debacle brought down the ministry of the Duke of Newcastle and swept in the new government of William Pitt.

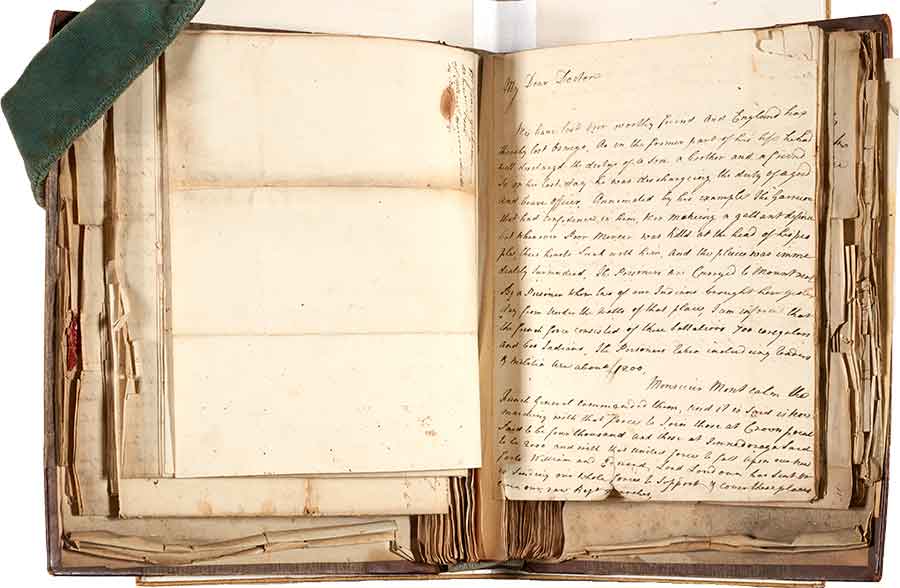

The James F. Mercer collection includes more than 120 letters, manuscripts, and documents, including James Grahame’s account of the fall of Fort Oswego.

This was all that was known about Col. Mercer. Nothing was known about his life, not even his age.

In January 2018, The Huntington's Library Collectors’ Council acquired a collection of Mercer’s correspondence, a welcome addition to the Library's famous holdings on the Seven Years’ War. Mercer’s letters to his brother William and friend James Grahame reveal the man behind the story of gore, defeat, and scandal.

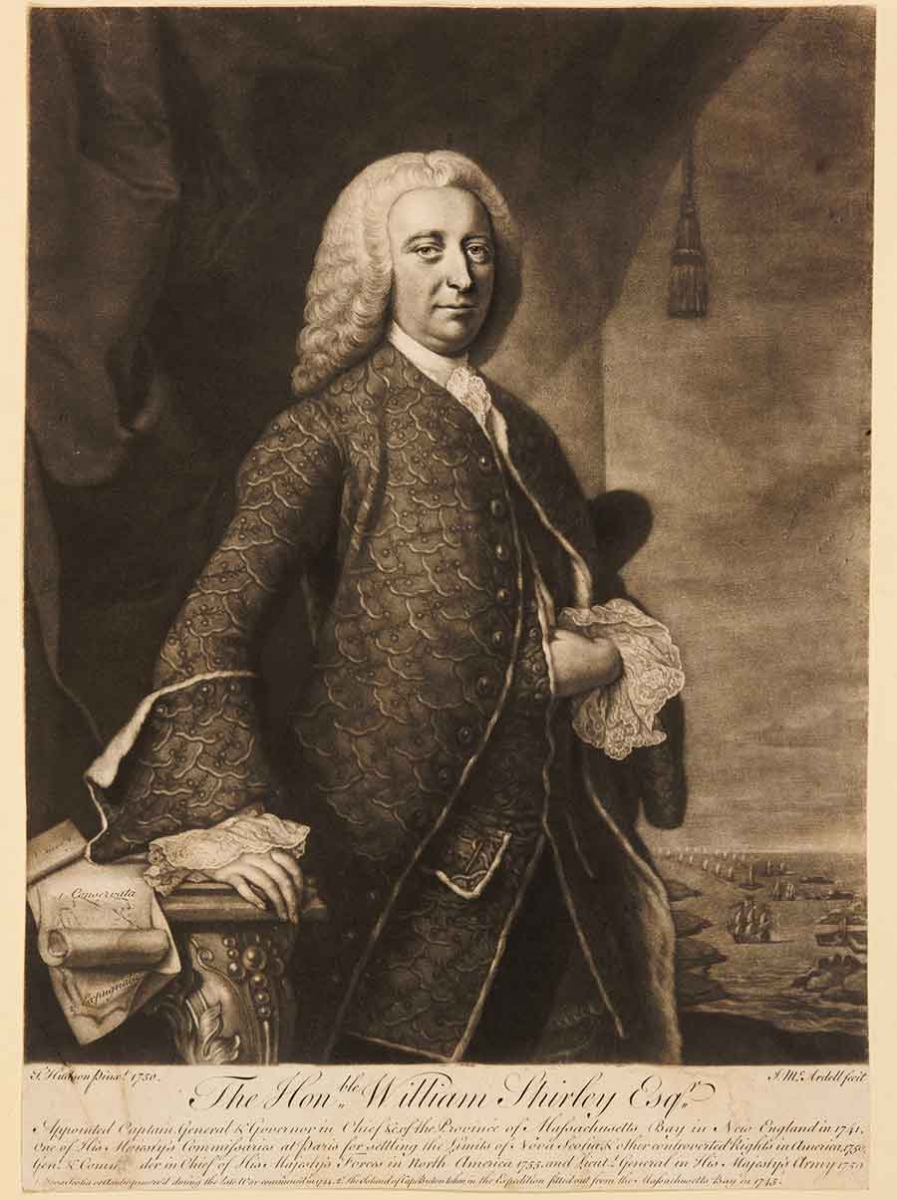

We first meet Mercer as a 27-year-old officer in Flanders, happily recounting a trip to Antwerp. In 1742, we find him in Jamaica. He spent the next eight years shuttling between London and his homestead in Scotland. In August 1754, he took a somewhat mysterious trip to France before sailing to America three months later. We next see him land in York, Virginia, “after being 56 days drag’d under water at the rate of a hundred miles a day,” on his transatlantic voyage, and then follow his journey to Boston, where he took charge of two regiments of New England recruits. And then we track his fateful journey to New York as he, under the command of Sir William Shirley, embarks on a military expedition to “the great cataract of Niagara.”

He never got there. At the end of August 1755, the men stopped at Oswego, “a small fort on a pocket of land” on Lake Ontario. It was supposed to be a brief stopover. Mercer was ready to carry on with, as he put it sarcastically, “a Laurel gathering,” but Shirley’s Niagara campaign came to an abrupt stop, with the commander hastily decamping for Boston. Mercer and his men were left stranded at Oswego. Mercer spent the last months of his life there, “in the back of God’s elbow,” oppressed by unrelenting misery as he watched his men freeze to death, picked off by the enemy or dying of “Scurvy and other distempers occasioned chiefly by the Severity of their living.”

Sir William Shirley (1694–1771). Engraving by J. McArdell after the portrait by Thomas Hudson. In December 1754, Shirley, the colonial governor of Massachusetts and a known war “hawk”—who, however, had never commanded a regiment, much less an army—was appointed to lead an expedition to Niagara. His second-in-command was James F. Mercer, in charge of some 2,000 American soldiers of the 50th and 51st Regiments of Foot. In October 1755, Shirley departed for Boston, leaving Mercer and his men at Oswego, N.Y.

All the while, he was writing home to his friend in London and his brother in Perth. The Mercer brothers shared a strong emotional bond and lived vicariously through each other. “Willie,” a happily married man safely ensconced in the family estate at Pitteuchar in Scotland, no doubt relished his brother’s tales of adventure.

William must have received a somewhat rosy version of military life from his older brother. Like many soldiers, Mercer avoided talking about the war when he had “an opportunity of speaking to [his] friends.” Mercer assured William that he was in “the most beautiful country in the world,” surrounded by the best men in the British army and facing very little danger. In June 1755, Mercer devoted a large portion of his letter home to praise the “great fidelity and affection” of his young servant, noting that “the goodness of his heart makes up for a slow genius.”

Mercer, who never got to have a family of his own, was much happier discussing “the government” of his brother’s family and “the progress of the Little ones.” The most extraordinary part of Mercer’s letters was his anxious concern for the education of his nieces—the seven-year-old Annie and five-year-old Peggy. He repeatedly implored his brother to “let the girls have as much learning as the boys & the boys as much as possible” and to ensure that the “poor girls . . . have the same advantages with your Boys.” Young women, he felt, needed more education than young men, for “knowledge is requisite to the Women to make them beloved & happy.”

Mercer was more candid in his letters to “Jaimie” Grahame. Grahame was not just a close friend, but also an agent who secured Mercer’s commissions and promotions, managed his accounts, and forwarded his letters home.

The English Lion Dismember’d, January 1757. This print shows treacherous government ministers dismembering the British lion while a French rooster tears at the national colors. The hind paw on the far side, marked “Oswego,” is still attached to the lion. The news of the fall of Fort Oswego reached London in early October 1756, plunging the nation into a major political crisis.

It was Grahame who took it upon himself to dispel the “Cruelle doubt” cast on Mercer by his commander, Shirley. Summoned to London to face charges of negligence and corruption, Shirley tried to “skrean” himself by blaming his dead officer for the loss of Fort Oswego.

Furious, Grahame put together an account of the events at Oswego, based on Mercer’s letters, written testimony of other officers, and Grahame’s interviews with the survivors. Grahame intended to submit this document as evidence against Shirley. The account was scathing: Shirley left Oswego without any orders, instructions, or supplies, and he ignored Mercer’s reports for months. The only communication Mercer ever received from his commander was an order to build boats to ship Shirley’s commercial goods.

Grahame’s effort came to nothing. The court of enquiry sputtered, as political scandals drowned calls for an investigation into the debacle. In the end, Shirley suffered no more than the equivalent of a slap on the wrist. Grahame died in 1760, heartbroken.

The Huntington’s acquisition of the Mercer archive will benefit historians of colonial America and Hanoverian Britain. It also helps to bring back to life a man who, in the words of one of his officers, died “at the head of his people,” having discharged “the duty of a good and brave officer,” just as “in the former part of his life he had well discharged the duties of a son a brother and a friend.”

Olga Tsapina is the Norris Foundation Curator of American History at The Huntington.