The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

A Renaissance Curiosity

Posted on Fri., Sept. 9, 2016 by

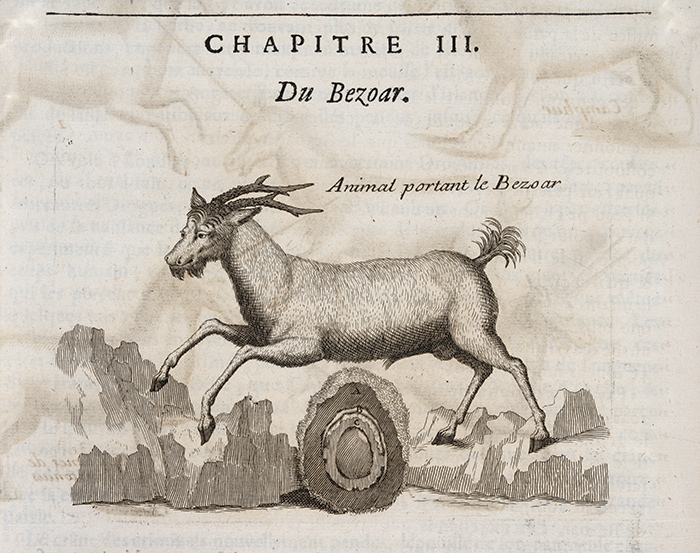

Detail from Pierre Pomet’s l’Histoire générale des drogues, Paris, 1694. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In J.K. Rowling’s novel Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, a quick-thinking Harry saves his best friend’s life by making him swallow a bezoar stone—a calcification from the stomach of a goat or other ruminant. Harry believed, as did many Renaissance doctors, that the stone served as a universal antidote to poison.

The Huntington’s collection of Renaissance printed books document the strange stone’s far-ranging use by apothecaries, medical practitioners, noble and royal collectors, preachers, and poets. In addition to nullifying the effects of poison, the fabulous stone reputedly cured worms, dispelled melancholy, and preserved youth.

The efficacy of the bezoar stone was put to the test in 1567, when Ambroise Paré, physician to King Charles IX of France, proposed a medical trial of sorts. He convinced a prisoner facing hanging to swallow poison along with the bezoar. If he survived, he’d be pardoned. The prisoner agreed and then died hours later, bleeding from every orifice and vomiting profusely, crying that death by gallows would have been better.

Yet the library record is packed with fantastic examples of the stone’s virtues and its soaring market value—equal to gold—that continued unabated long after Paré’s experiment.

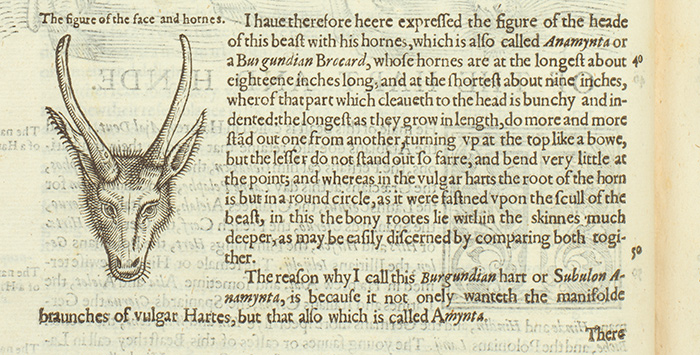

Detail from Edward Topsell’s The historie of foure-footed beastes, London, 1607. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Pierre Pomet, a French apothecary, summarized the Renaissance romance with bezoar stones. Harvested from wild goats or sheep in Persia, the East Indies, or Malaca, bezoars evoked the exotic allure of far-away lands, even as they promised to cure the human body. An image from Pomet’s 1694 l’Histoire générale des drogues shows an animated male goat caught in mid-leap among rocky cliffs, emphasizing the stone’s unusual genesis: a concretion bred in an animal but composed of a mineral.

Another Renaissance belief held that bezoars formed from the tears of a weeping stag. Edward Topsell’s The Historie of foure-footed beastes, published in 1607, describes a particular hart or deer that regenerated itself by eating venomous serpents. The hart dispelled the poison by submerging itself in water. According to Topsell, “The teares of this beast . . . are turned into a stone (called Belzahard, or Bezahar) . . . and being thus transubstantiated doe cure all manner of venom.”

Bezoars appeared in inventories of monarchs from the Hapsburg Rudolph II to England’s Queen Elizabeth I and were often displayed proudly alongside their royal jewels. Bezoar stones were also key ingredients in the tonics proposed by Renaissance physicians and apothecaries, as well as the home remedies offered by mothers and wives.

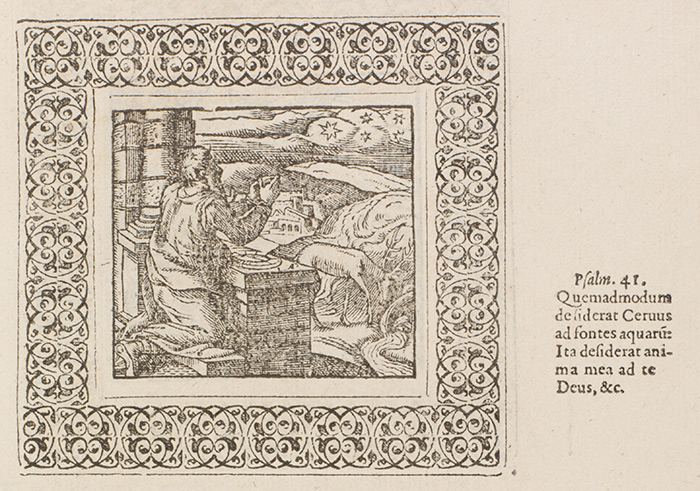

Detail of venomous serpents and a bezoar-weeping hart from Hortus sanitatis, Strassburg, approximately 1507. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The bezoar’s powers encompassed both physical and spiritual cures. Robert Burton, in The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621), recommends the bezoar for its “especiall vertue against all melancholy affections” because “it comforts the heart and corroborates the whole body.” As a prophylactic against bodily poisons, the bezoar could be readily cross-purposed for a spiritual antidote.

In the Psalms of David, Psalm 41, a thirsty, panting hart, frequently conflated in commentary with the bezoar-weeping stag, illuminates the struggle of the soul. As translated by the Protestant poet and courtier Sir Philip Sidney (1554-1586), the psalm reads:

As the chafèd hart, which brayeth,

Seeking some refreshing brook,

So my soul in panting playeth,

Thirsting on my God to look.

The sweating, crying hart, an emblem of the human soul, seeks the cure to relieve spiritual melancholy.

Detail from Geoffrey Whitney’s A choice of emblemes, London, 1586. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

How, I wondered, did a fragile calcification find such a prominent place among the great Renaissance curiosity cabinets, jewel houses, and royal recipes? Why did it feature in so many sermons, poems, and romances as an elixir of life?

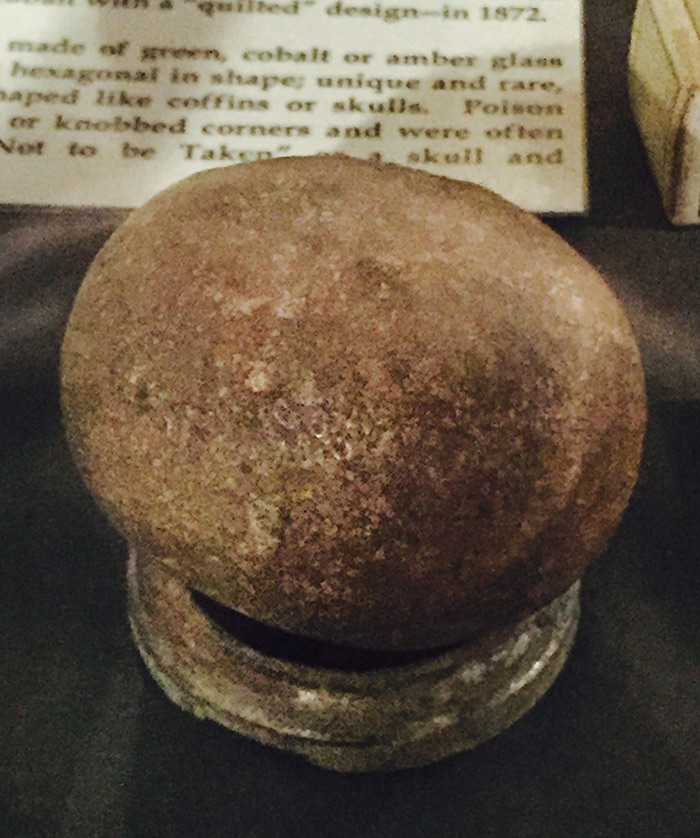

My curiosity grew when I was able to observe a real bezoar. On a recent trip to Louisiana, I was delighted to discover a bezoar stone at the New Orleans Pharmacy Museum. It was sitting alongside other questionable medical treatments such as cocoa and “gris-gris,” a potion used by Voodoo practitioners. Amused by my excitement, the curatorial staff gave me the bezoar to hold. I expected a heavy, stone-like weight; instead, I held what felt like an eggshell. It was also incredibly plain without a hint of sparkle.

What was treasured by the Renaissance heart and mind might hold little appeal in today’s bling-blinded world. But to this researcher, at least, the delicate and unassuming object was weighty with significance, offering insight into an era when a byproduct from an animal’s digestive tract might be a precious stone with extraordinary powers.

A bezoar stone at the New Orleans Pharmacy Museum. Photo by Tiffany Jo Werth.

Tiffany Jo Werth is associate professor of English at Simon Fraser University and the 2016–17 Mellon Fellow at the Huntington. Her current book project, from which this post draws, is “The Lithic Imagination from More to Milton.” She is the author of The Fabulous Dark Cloister: Romance in England after the Reformation, available from Johns Hopkins University Press.