The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Preserving the Signs of Censorship

Posted on Mon., April 24, 2017 by

Kristi Westberg, the Dibner Book Conservator at The Huntington, works to preserve a copy of Primum mobile (Prime Mover), an astronomy book by the Austrian humanist and astronomer Erasmus Oswald Schreckenfuchs (1511–1579). Photo by Kate Lain.

Five hundred years before government officials in some countries got in the business of censoring Instagram feeds or Twitter accounts, the Roman Catholic Church was using ink to black out text that it considered dangerous. Censors went through books, including scientific texts, and crossed off portions that defied Church doctrine. One such book is The Huntington’s copy of Primum mobile (Prime Mover), an astronomy book by the Austrian humanist and astronomer Erasmus Oswald Schreckenfuchs (1511–1579).

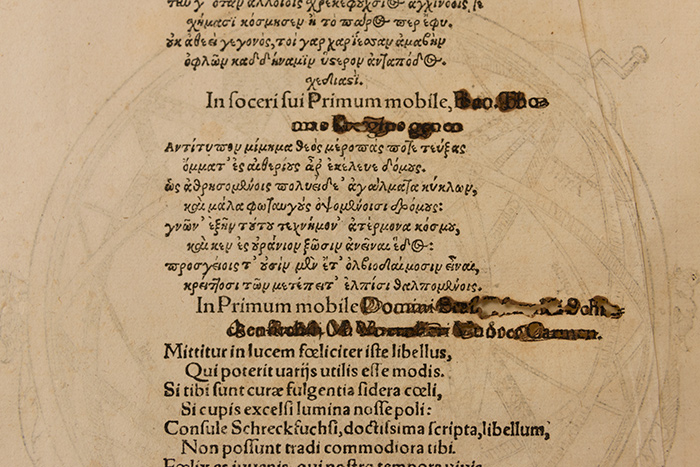

This copy of Primum mobile was typeset by hand, printed on high-quality rag paper, and bound in parchment. Despite being 450 years old, it barely shows its age. The title page displays an illustration of an armillary sphere—an ancient astronomical device that reproduces a model of the celestial sphere—with the Earth at its center, but there are several brown ink spots that mar the image. When you turn the page, it becomes evident that the book’s censor, blacking out some offending text, applied iron gall ink, a compound made of iron salts and tannic acids.

The book’s censor, blacking out some offending text on the back of the title page, applied iron gall ink, a compound made of iron salts and tannic acids. Photo by Kate Lain.

Iron gall ink is more permanent than carbon ink, and over time, its intense blue-black color fades to brown. Under certain conditions, including high humidity, iron gall ink can corrode and damage the paper beneath it. Several of the blacked-out areas of this volume showed signs of corrosion, and the most dramatically damaged areas had small holes and text losses where the censor applied ink more heavily.

As a book conservator, my challenge was to repair the fragile areas of the obscured text without adding additional moisture that could accelerate the chemical reactions causing the holes. The solution? Solvent set tissue. This type of repair tissue is perfectly suited to such a problem. It is very lightweight but strong thanks to its long fibers, and with a little preparation, it can be adhered to weak areas of the text with ethanol, a solvent that evaporates quickly.

Solvent set tissue is made by applying a special adhesive on a piece of thin polyester, dropping a lightweight piece of Japanese paper on top, and then waiting for it to dry. Photo by Kate Lain.

Solvent set tissue is made by applying a special adhesive on a piece of thin polyester, dropping a lightweight piece of Japanese paper on top, and then waiting for it to dry. In this case, I used Klucel G, a flexible adhesive that can be dried and reactivated with water or ethanol. (Head to Tumblr to see how solvent set tissue is made.)

I then cut a small piece of the coated tissue to the shape of the hole, extending it a little beyond the degraded paper to the more stable and flexible unmarked page. I brushed Ethanol on a black tile to insure even application of the solvent and to help me see the nearly transparent repair piece. Next, I dropped the repair piece on top of the brushed-out Ethanol to reactivate the adhesive.

Westberg brushes Ethanol on a black tile to insure even application of the solvent and to help her see the nearly transparent repair piece. Photo by Kate Lain.

Using a pair of fine tweezers, I lifted the repair tissue off the tile, placed it on the degraded part of the text, and tamped it down with a soft brush. To ensure the newly repaired area remained flat and completely dry, I placed a piece of smooth, porous fabric called Hollytex on top of it, along with a dry blotter and a light weight. I repeated this process on several parts of the page to provide support to the fragile areas.

Using a pair of fine tweezers, Westberg places the repair tissue on the degraded part of the page and tamps it down with a soft brush. Photo by Kate Lain.

After several hours of carefully cutting and placing repairs, I was pleased with the stability of the degraded areas. While these repairs might seem small, they are important to the overall preservation of this rare copy of Prime Mover. The censored areas have become an integral part of the volume, so repairing the weaknesses and text losses help to make it safe for use by researchers. I don’t support censorship, but I do support preserving evidence of the practice.

A close-up of Westberg’s repair work on the title page of Primum mobile. Photo by Kate Lain.

The American Library Association’s Preservation Week runs from April 23–29. For more information, visit their Preservation Week website.

Kristi Westberg is the Dibner Book Conservator at The Huntington.