The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Isherwood in California

Posted on Thu., Nov. 5, 2015 by and

The conference “‘My Self in a Transitional State’: Isherwood in California” takes place at The Huntington on November 13 and 14 in Rothenberg Hall. We asked the conference conveners—James J. Berg, dean of the School of Arts and Sciences at College of the Desert, and Chris Freeman, professor of English at the University of Southern California—to share their view of developments in Isherwood studies.

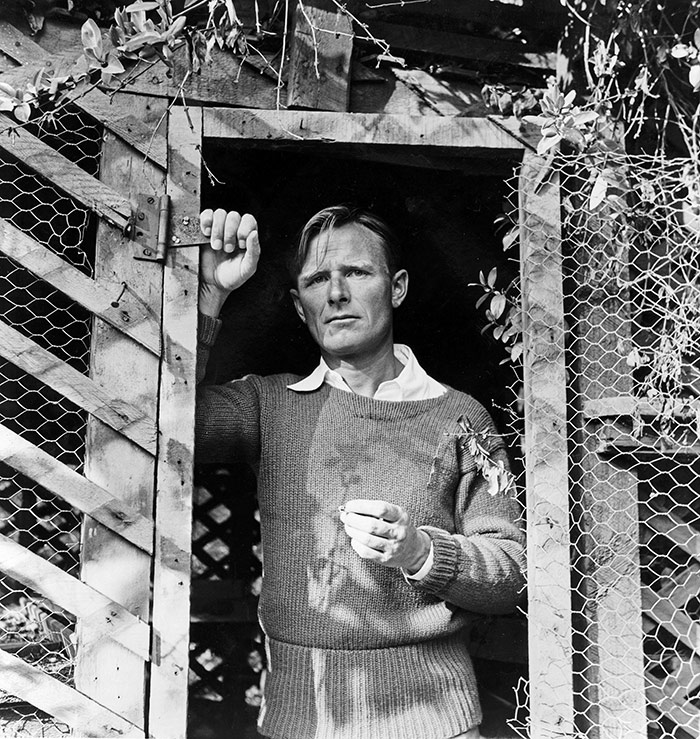

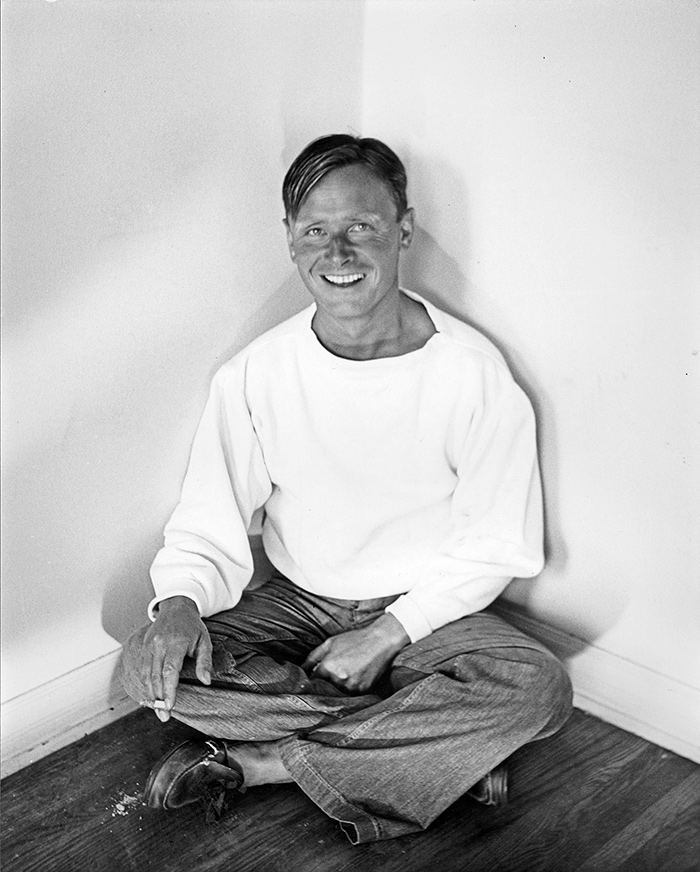

Christopher Isherwood in Santa Monica, ca. 1950. Photo by William Caskey. The Huntington’s Isherwood collection includes literary drafts, diaries and journals, photographs, audio and videotapes, and letters from many authors, including W. H. Auden, Truman Capote, E. M. Forster, Somerset Maugham, Stephen Spender, Gore Vidal, and Tennessee Williams. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

When we first began looking at the life and work of Christopher Isherwood, it was 1996 and the Anglo-American writer had been dead for 10 years. Even though we were in the heyday of gay studies and queer theory in the academy, it seemed that almost no scholarly activity had been done on this writer who sometimes saw himself—as he noted in his diary in 1941—as being both “remote and obscure.”

In the past 20 years, several important publications on Isherwood have appeared: the first volume of his million-word Diaries (1996), a major new biography by Peter Parker (2004), and our own collection of essays, The Isherwood Century (2000), which we followed up two years later with Conversations with Christopher Isherwood. The University of Minnesota Press also brought out new editions of nearly all of Isherwood’s works, bringing back into print several titles that had become difficult to find. Three films—two adaptations of his work (A Single Man and Christopher and His Kind) and a documentary (Chris and Don: A Love Story)—have also expanded Isherwood’s audience. No longer is he known only as the author of Cabaret.

The other major development in Isherwood studies is significant for perpetuity: in the late 1990s, the Huntington acquired Isherwood’s papers from his longtime partner, the artist Don Bachardy, and, with The Christopher Isherwood Foundation, established a visiting fellowship for scholars studying the writer’s works.

The Huntington’s acquisition of the vast Isherwood archive and the subsequent scholarship that has been done by Isherwood fellows and others using the material have contributed to a reevaluation of the writer’s work, particularly from an American scholarly view and for an American context. Many of the scholars convening at The Huntington for the conference “‘My Self in a Transitional State’: Isherwood in California” have made extensive use of the Isherwood archive and will connect the writer to his American contemporaries, the culture and history of Southern California (including the film industry and Eastern religions), and the movement for gay and lesbian rights.

At a recent event in Palm Springs in support of our new book, The American Isherwood, the novelist Katherine V. Forrest called Isherwood “a prince of gay literature.” Forrest is among many American writers who appreciate the importance of Isherwood’s work. As Stephen McCauley wrote in the preface to The American Isherwood, “You can open any Isherwood novel at random and discover a paragraph so filled with wit, insight, and unaffected elegance that you’re inspired to wrestle with words a little longer and strive for his level of excellence.”

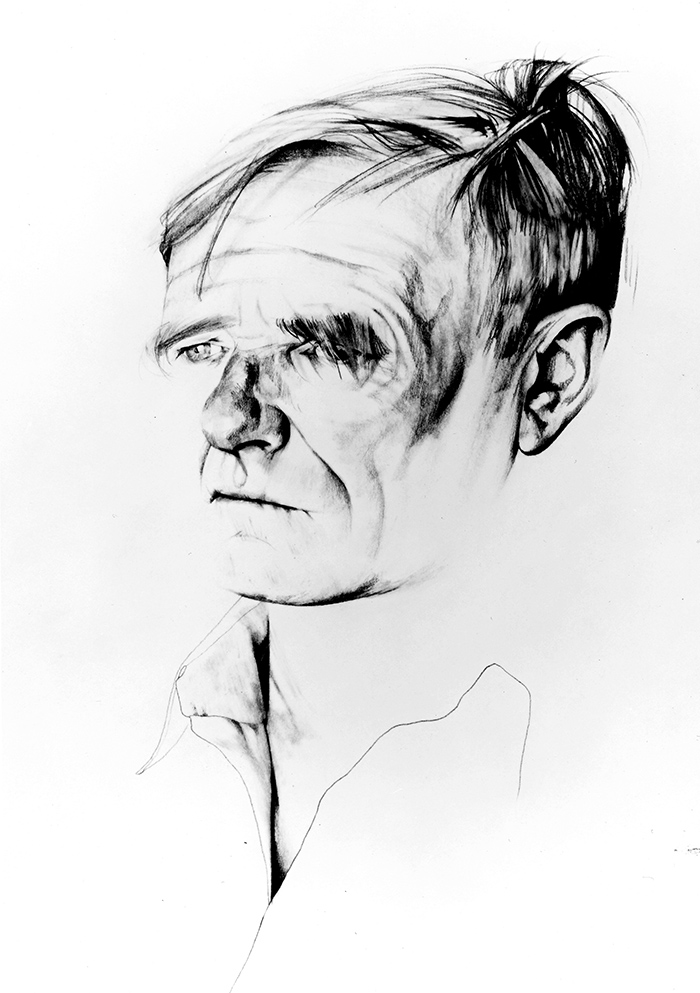

Christopher Isherwood, ca. 1950. Photo by William Caskey. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Author Armistead Maupin, whose Tales of the City series was praised by Isherwood as “Dickensian,” was a friend of Isherwood and Bachardy. He wrote in his foreword for our book The Isherwood Century, “no other figure in my life made me feel more connected to a past I had never known and a future I had yet to realize.” Maupin has coined the term “logical family” (as opposed to “biological family”) to describe the families that LGBTQ people choose to keep in their lives. We are looking forward to his lecture on November 12, citing Isherwood as his “Logical Grandfather,” which will be an inspiring prelude to the conference.

Maupin, McCauley, and Forrest exemplify that most ephemeral of literary ideas: influence. Isherwood’s influence on American culture and letters is the underlying theme of “My Self in a Transitional State,” and the scholars gathering for this conference will examine Isherwood’s legacy as an American writer and explore the continuing interest in his life and work.

Related content on Verso:

Two Singular Men, One Berlin (Oct. 27, 2014)

A Single Manuscript (Feb. 26, 2011)

James J. Berg is dean of the School of Arts and Sciences at College of the Desert.

Chris Freeman is professor of English at the University of Southern California.