The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

The Huntington’s Very Own “Monuments Man”

Posted on Wed., Feb. 5, 2014 by

American GIs hand-carried paintings down the steps of the Neuschwanstein castle under the supervision of Captain James Rorimer. (Photo credit: NARA / Public Domain)

In 1951, Theodore A. Heinrich was appointed curator of the Art Collections at The Huntington. He came equipped with impressive credentials, including degrees from the University of California and Cambridge University, and had studied in France and Germany before doing research on 18th-century British art. What many may not have known is that this art curator had made a major contribution to the preservation of looted art and damaged cultural resources during and after World War II.

The release of the new movie "The Monuments Men" will finally give prominence to the story of the small cadre of allied soldiers who worked tirelessly, often without critical resources or support, to follow front-line troops into battle and to secure, stabilize, and repatriate cultural resources. Drawn from the ranks of American and British museums and universities, this band of about 400 citizen soldiers was doing something that had never been done on this scale in history. From shattered cathedrals to looted art collections, these Monuments Men contended with a maelstrom of war fought on a scale never before waged. At the same time, the state-sanctioned looting by the Nazis was conducted with intense precision at an industrial pace.

I first heard of Mr. Heinrich when I was a teenage volunteer at The Huntington. My mentor, Edwin H. Carpenter, had retired from the Library but still came to work daily at The Huntington like so many former staffers do. Ed had served with Gen. George Patton in North Africa and Italy. He loved to talk about his wartime experience. At some point, the subject of Nazi looting came up, and we talked about how the loss of Europe’s precious artistic treasures could have been much worse.

The milestone was Franklin D. Roosevelt’s formation of the Roberts Commission, which established the Museums, Fine Arts, and Archives (MFAA) branch within the Civil Affairs and Military Government Sections of the Allied armies. After the war, the Roberts Commission helped the MFAA and Allied Forces return Nazi-confiscated artworks to rightful owners. It also promoted public awareness of looted cultural works.

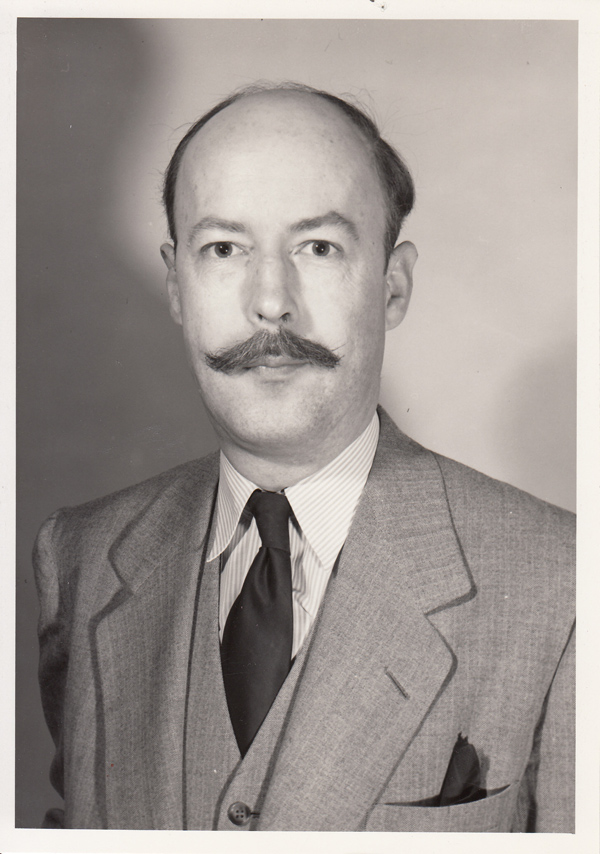

Theodore Heinrich in 1951. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

My conversations with Ed took place long before most of the seminal books on the subject were published, and it was all fantastically interesting to me. He mentioned that one of our former curators—Theodore Heinrich—had served as part of this effort. While his wartime service focused mainly on military matters, the arrival of victory in 1945 allowed Heinrich to work with the MFAA serving as chief of the MFAA Branch of Military Government for the German state of Hesse. He worked in Munich and Wiesbaden, where he ran collecting points that amassed millions of pieces of artwork and sought to find their rightful owners.

Heinrich remained in Germany until 1950 assisting local officials with the rebuilding of their museums, libraries, and archives. He was awarded a Bronze Star in 1946 and a Belgian Croix de Guerre for his restitution work.

In 1950, Heinrich wrote an article on behalf of the Allied High Command where he described the large-scale temporary removal of artworks from Europe to the United States for safety and conservation reasons. It was clear that at the time many in Western Europe thought the U.S. had helped itself to the "spoils of war."

In fact, Heinrich worked tirelessly to make sure that the artworks made it back to museums in Germany once the institutions could safely keep them (these particular works had been in German museums before the war). Before they did, however, the objects went on tour in Washington, D.C., and 12 other American cities, and ultimately were viewed by 2.5 million people. Two years later, Heinrich worked to take the same exhibition through German cities so that Germans could see that not every last morsel of beauty was lost in the war—and that the Allies kept their promise to return what was taken.

Heinrich left The Huntington in 1952 to join the Metropolitan Museum and later became the director of the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto. He subsequently worked as a professor of art history at York University until his death in 1981.

These Monuments Men, including Heinrich and others, are rightly honored alongside our greatest heroes. Their valor in preserving the examples of the finest achievements of human creative endeavor so that an entire culture’s artistic history was not destroyed by war and indifference is something everyone should celebrate. And it's an honor for us at The Huntington to know that there is an institutional connection to this monumental chapter in modern history.

Randy Shulman is the vice president for advancement at The Huntington.