The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Empowering the Earl of Leicester

Posted on Thu., May 26, 2016 by

Map of the British Isles, Heroica Eulogia, William Bowyer, 1567. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The Huntington possesses an astonishing Elizabethan-era illuminated manuscript, dating from 1567, entitled Heroica Eulogia. Containing a series of vignettes of earls and kings, it is an exquisite volume that combines paintings, coats of arms, Latin poems, 14 distinctive styles of handwriting, and historical documents. Its author (although “producer” might be a better word) was William Bowyer, the Keeper of the Records in the Tower of London.

For years, the beauty of this manuscript captured the attention of calligraphers, who identified it as the work of French calligrapher John de Beauchesne, author of the first Elizabethan handwriting manual. Its rich heraldic representations also have caught many people’s eyes—including those of curators at the Folger Shakespeare Library, who borrowed it once for an exhibition. But the manuscript’s major claim to fame is its color map of Britain, one of the earliest accurate maps of the British Isles.

Recently, we decided to display and discuss Heroica Eulogia at a Huntington event and took a moment to reconsider this amazing volume. Putting aside for a moment its decidedly beautiful images, what was its purpose? Why was it produced, in what context was it prepared, and what did it mean?

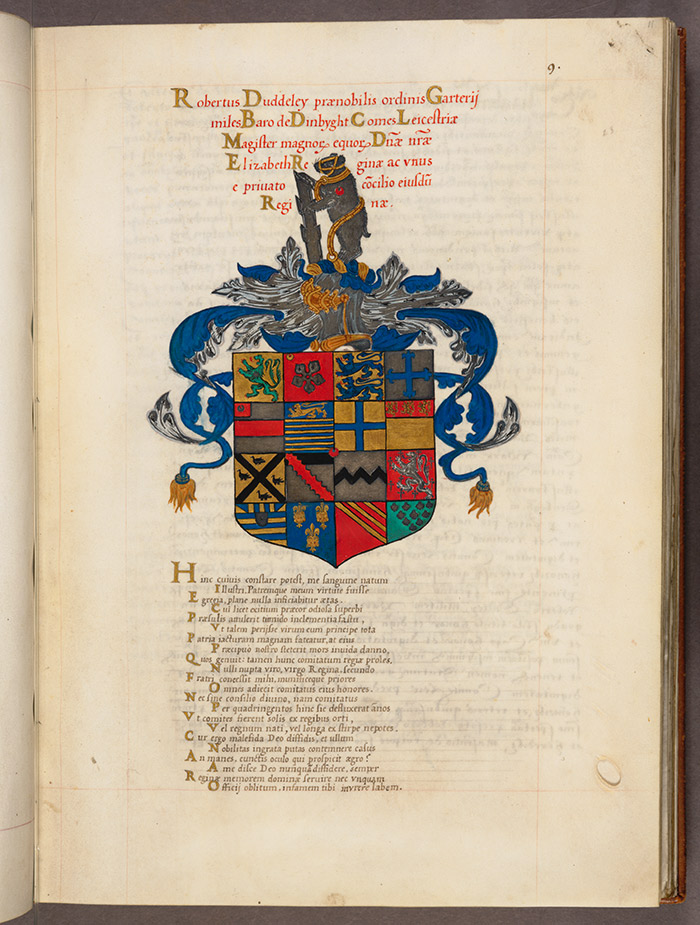

Arms of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, with verses in the calligraphic script of John de Beauchesne, Heroica Eulogia, William Bowyer, 1567. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

We had two significant clues. For one, Bowyer dedicates the volume to the newly created Earl of Leicester, Robert Dudley (1532–88)—the favorite and suitor of Queen Elizabeth (1533–1603), the self-styled Virgin Queen. The second clue appears on the title page in the form of a riddle in Latin: “Venit veritas interdum in lucem non quaestia.” Or, in English: “Sometimes the truth comes to light unsought.” What truth was this manuscript teaching Leicester that he didn’t realize he needed to know?

The more we examined the volume, the more we felt convinced that Bowyer was teaching the new Earl of Leicester about his rights and powers, basing them on the histories of former earls of Leicester and on the properties Queen Elizabeth had granted him. That would explain the inclusion of the extents, deeds, parliamentary writs, and other documents that verified Leicester’s rights, as earl, to the powers of all previous earls.

It also seems that Bowyer was trying to prove Robert Dudley was worthy of marrying Elizabeth. The Queen had made it clear that, of the many suitors who pursued her, she favored Dudley, though he was already married. When Dudley’s wife died mysteriously, the path was seemingly cleared. But Elizabeth, wisely realizing that marrying a man assumed by many to have murdered his wife would undermine her authority, let the idea go. In Heroica Eulogia, Bowyer includes a poem lauding Dudley’s merit, including a line about his being unmarried and the Queen’s being a virgin, making the obvious suggestion.

Edward I seated in a triumphal car, Heroica Eulogia, William Bowyer, 1567. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Elizabeth went on to give Dudley Kenilworth Castle, the barony of Denbigh, and Chirk Castle—making him rich enough to be an earl, with huge power in the Midlands and North Wales. In the manuscript, Bowyer reproduced documents pertinent to previous possessors of these lands.

Prefacing these historical documents were symbolic portraits of English kings, each with a Latin poem recounting his life and fortunes. Of these, a particularly telling one shows Edward I (1239–1307) riding in a Roman triumphal car. Above him floats a banner declaring: “I fix my eyes on God, turning neither to the right nor to the left.” Edward stands over conquered Scotland and Wales, and the Pope falls off the back of the car. Surrounding Edward are the virtues of “necessary war,” “policy,” “magnanimity,” “just cause,” “clean conscience,” and “tireless work.” The message is clear: Edward was a righteous king who justly conquered England’s foes.

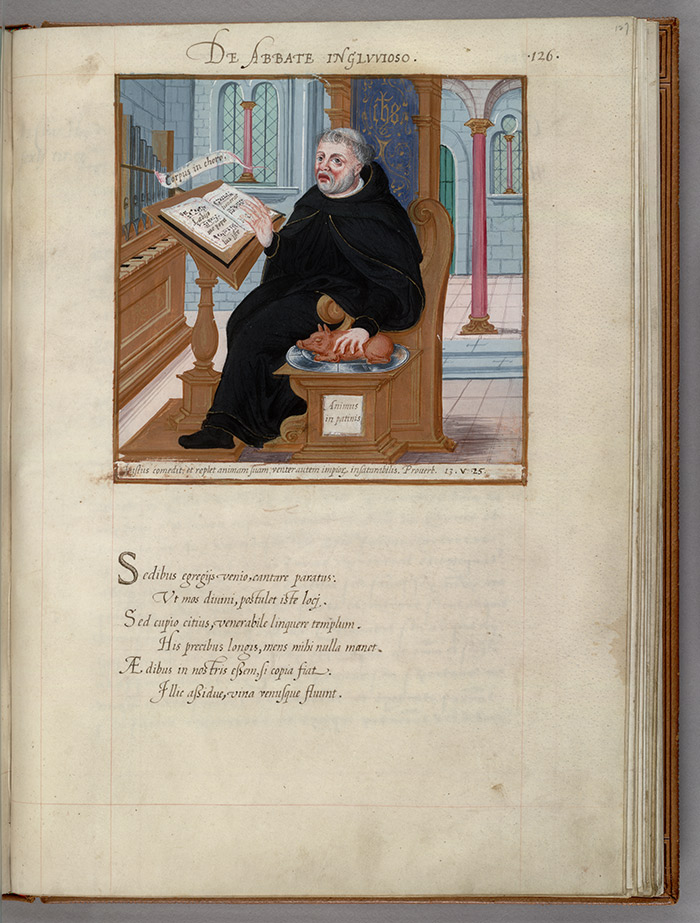

The volume also contains cartoons justifying the dissolution of monasteries and priories whose property and powers are being granted to Leicester. They declare their corruption, with titles such as “The Avaricious Monk,” “The Careless Bishop,” and “The Hypocritical Friar.” The images are accompanied by stern biblical passages about corruption being purged by divine wrath. Each image is accompanied by a Latin poem written in a mocking tone that imitates the work of the Goliards, medieval poets who satirized clergy and liturgy.

“De abbate ingluvioso,” Heroica Eulogia, William Bowyer, 1567. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

One image shows a gluttonous, ruby-cheeked abbot. His open hymnbook reveals that he’s worshiping the Pope. While he’s singing of “the body in the choir,” a roasted piglet sits beside him on a platter, labeled in Latin “Animus in patinis,” a pun on “paten,” the plate on which the bread—the body of Christ—rests during the mass. The label suggests that the abbot’s heart is fixed on pork, not on Christ.

In the end, we do not know if the Earl of Leicester ever received this volume. Parts of it are not finished, suggesting that it may never have been delivered. What we do know is that Bowyer had an imaginative and powerful multimedia technique of making the case for the earl’s powers. Using historical evidence, poetry, and painting, Bowyer had master craftsmen produce a unique manuscript that explored the powers of the earl. This magnificent volume provides a rich, lively, and detailed look at how history and art supported the hierarchies of power in Elizabethan England.

You can listen to Norman Jones’s Distinguished Fellow lecture, “Being Elizabethan: How Elizabethans Made Sense of Their World,” on SoundCloud or iTunes U.

Norman Jones, the 2015–16 Fletcher Jones Foundation Distinguished Fellow at The Huntington, is professor of history at Utah State University. Among his recent books are The English Reformation: Religion and Cultural Adaption and Governing by Virtue: Lord Burghley and the Management of Elizabethan England .