The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Reading and Rereading Hilary Mantel

Posted on Wed., Oct. 13, 2021 by

Hilary Mantel by Clare Park©

Hilary Mantel, whose literary archive is held at The Huntington, is one of the most critically acclaimed authors working today. Her unprecedented double Booker Prize wins for Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies, combined with sold-out West End and Broadway stage adaptations and award-winning television dramatizations, have brought her to wide public prominence.

On Sept. 23, 2021, at the Gielgud Theatre in London’s West End, the curtain went up on the stage adaptation of The Mirror of the Light, the final novel in Mantel’s trilogy about the career of Thomas Cromwell in the court of King Henry VIII. This most recent chapter in Mantel’s literary career, which spans more than three decades, once again places the author center stage and offers an ideal moment to initiate a new series of debates about her work during The Huntington’s online conference “An Overflow of Meaning: Reading and Rereading Hilary Mantel” on Oct. 14 and 15.

Mantel is an author whose diverse body of literary work—spanning novels, short fiction, criticism, journalism, life writing, and drama—has challenged and provoked scholars since the emergence of the field of Mantel studies roughly a decade ago. Our virtual conference, for the first time, will bring together an international group of scholars to investigate the implications of Mantel’s writing for the field of contemporary literary studies, asking how these heterogeneous texts change the ways it is possible to think about such issues as our relationship with the historical past and the familial dead; the practice of medicine and experience of illness; the construction of nation; and the haunting presence of voices, events, and individuals who have slipped from collective memory.

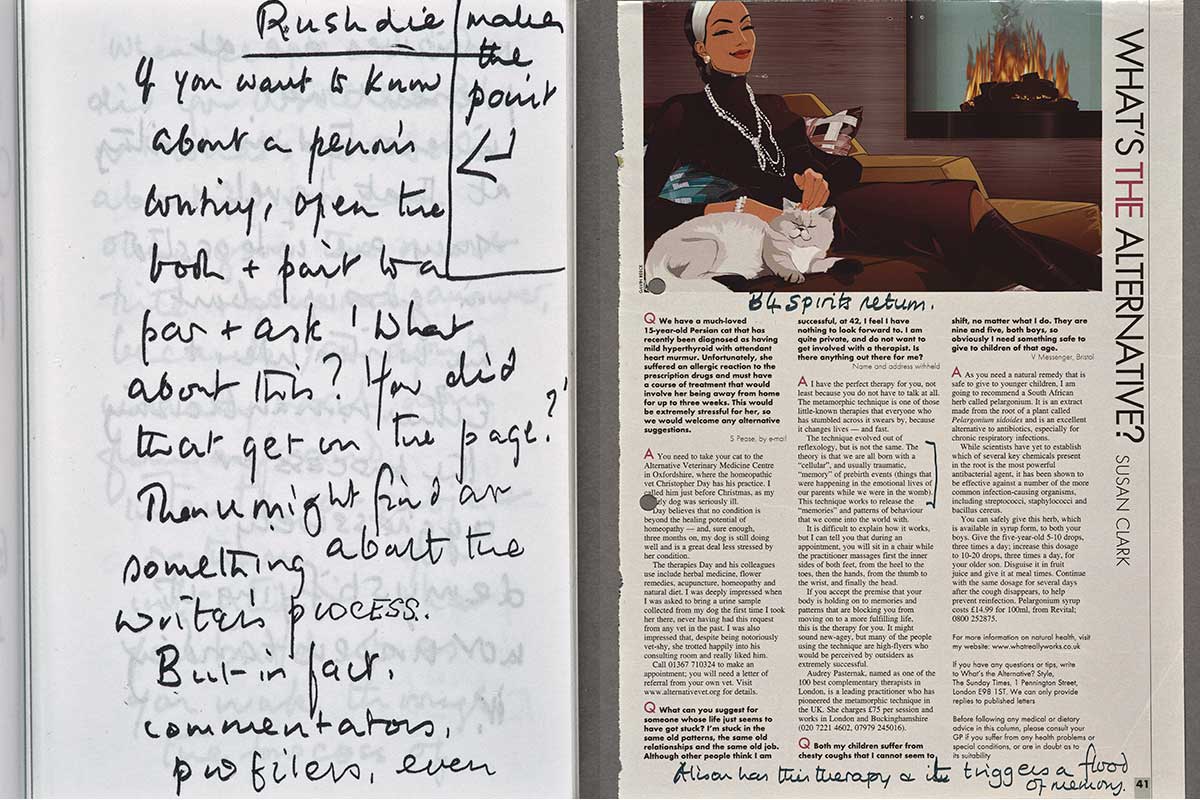

In a short prose fragment among her papers, Mantel recalls the words of Salman Rushdie, advising on the best way to understand a writer’s process: “If you want to know about a person’s writing, open the book [and] point to a page [and] ask ‘What about this? How did that get on the page?’” Such a question might also find its answers within Mantel’s literary archives. The drafts, correspondence, fragments, and ephemera held by The Huntington offer striking insights into the interaction between the author’s fiction and the world in which it is created and consumed. For example, an advice column recommends a therapeutic regression to the womb and finds its way into Mantel’s reflection on millennial mediumship in Beyond Black (2005).

Left: Extract from a small pocket notebook of Hilary Mantel’s research notes. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Right: Hilary Mantel’s notes on “What’s the Alternative,” an advice column in the Style Magazine of the Sunday Times. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Left: Extract from a small pocket notebook of Hilary Mantel’s research notes. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Right: Hilary Mantel’s notes on “What’s the Alternative,” an advice column in the Style Magazine of the Sunday Times. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

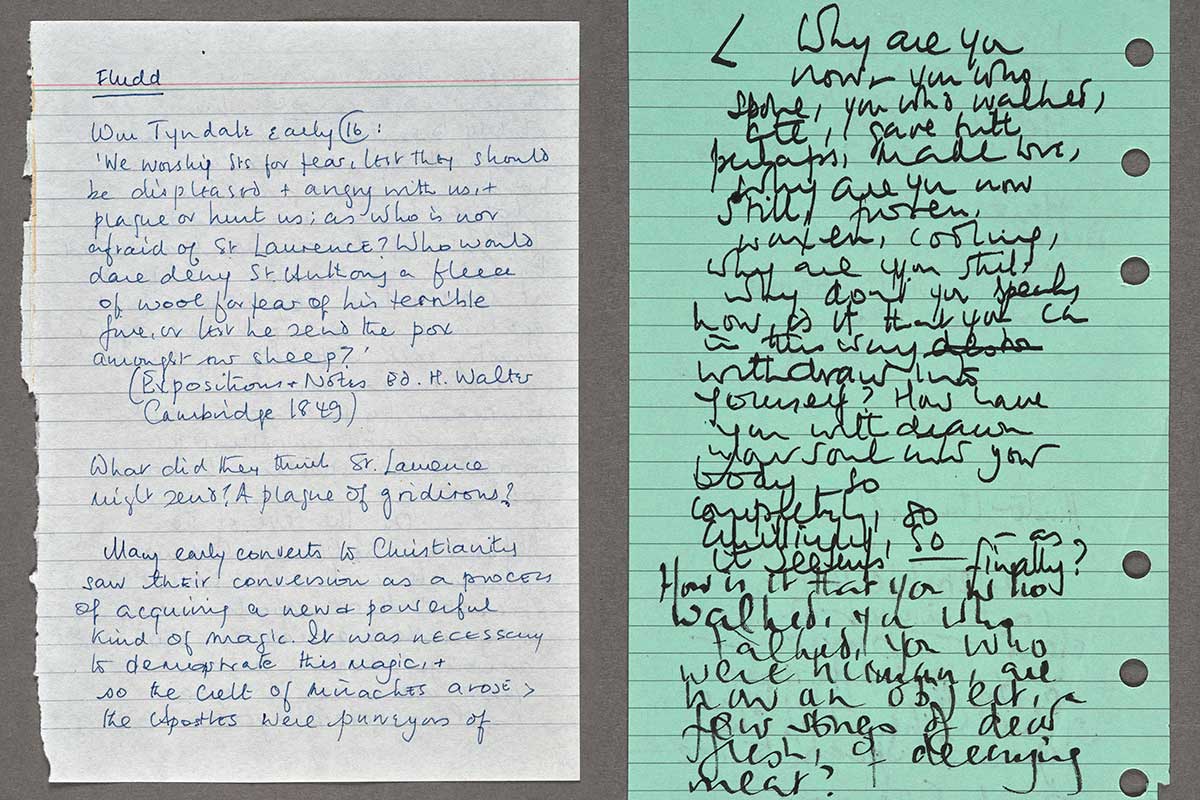

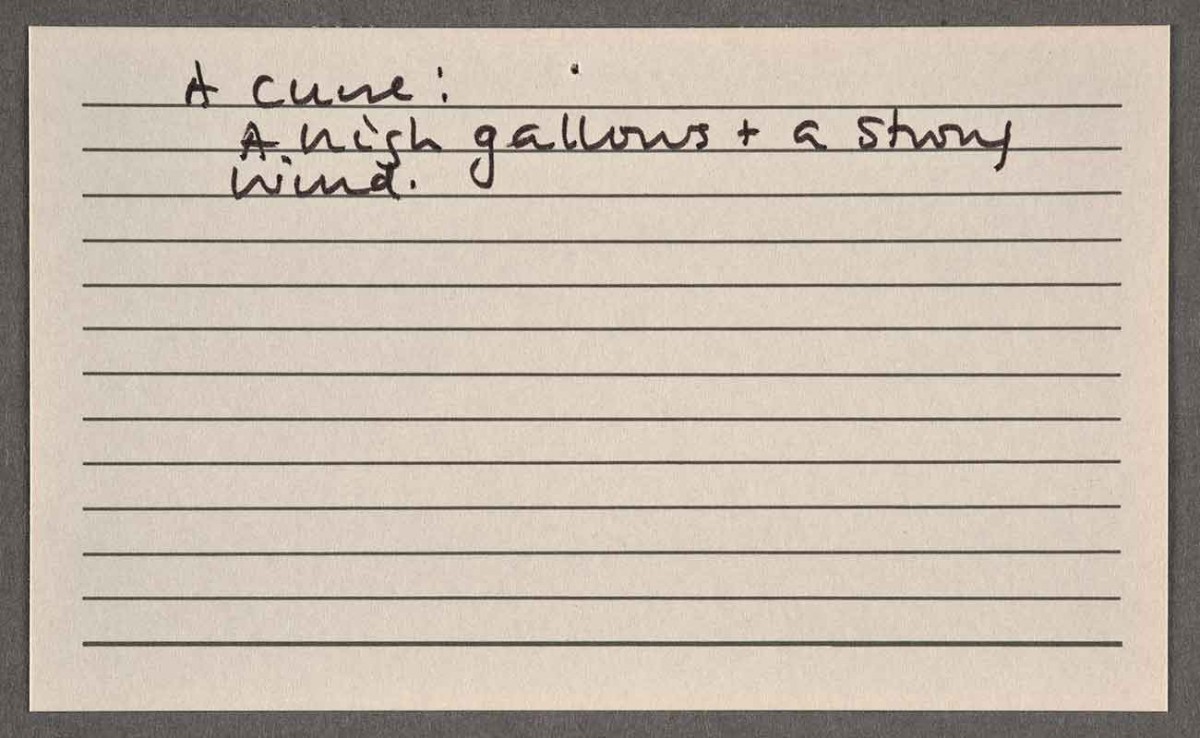

Mantel folds the reflections of the 16th-century biblical translator William Tyndale on the function of saints into her alchemical-clerical novel Fludd (1989) and footnotes them with her own meditation on the idiomatic nature of divine retribution—wryly asking, “‘What did they think Saint Lawrence might send? A plague of gridirons?’ A curse—‘A high gallows and a strong wind.’” This meditation later appears in the pages of The Giant O’Brien (1998), a novel that explores heritage, migration, and exploitation alongside anatomy and body snatching.

Studying literary archives is not, however, an exercise in authorial “hide and seek,” in which textual extracts are pinned uncomplicatedly to their original inspirations. Instead, accessing the working papers of an author such as Hilary Mantel offers the opportunity to trace the spectral threads of connection that are woven throughout her oeuvre, allowing new resonances between texts to emerge.

Left: Hilary Mantel’s notes on William Tyndale’s view of saints for her novel Fludd (1989). The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Right: Anatomist John Hunter addresses the dead in an early draft of Hilary Mantel’s novel The Giant O’Brien (1998). The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Left: Hilary Mantel’s notes on William Tyndale’s view of saints for her novel Fludd (1989). The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Right: Anatomist John Hunter addresses the dead in an early draft of Hilary Mantel’s novel The Giant O’Brien (1998). The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Moreover, the documents offer further insights into the ethical and philosophical discourses that Mantel’s work contributes to and complicates. In an early draft of The Giant O’Brien, anatomist John Hunter demands: “Speak to me!—Oh dead persons, speak. Why are you now, you who walked, ate [. . .] why are you now still? [. . .] How is it that you who walked, you who talked, you who were human, are now an object?”

These lines invite a reflection on the nature of mortality, on how the hands of the dead are laid on the living and how the living alternately grasp at and flinch from them—a reflection that ties into current debates regarding the ways the historical dead are memorialized and the availability of those memorials for reinterpretation.

A curse that appears in Hilary Mantel’s novel The Giant O’Brien (1998). The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

A curse that appears in Hilary Mantel’s novel The Giant O’Brien (1998). The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The conference seeks to generate similar contributions to a wide range of contemporary discourses, bringing together scholars from the fields of literature, history, law, art history, and psychology to spark new approaches to the questions posed by Mantel’s complex and compelling body of work.

Lucy Arnold is a lecturer of contemporary English literature at the University of Worcester.