The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

A Real Fake: The Shakespeare Forgeries of William Henry Ireland

Posted on Wed., April 22, 2020 by

Image of William Henry Ireland, an engraving made in 1803. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The term "fake news" now features prominently in our cultural lexicon. While the nuances are unspoken, we tend to assume that fake news is the opposite of real news, or fact-based news. We like to believe that these are easy and clear distinctions to make, but that is not always the case. In late-18th-century London, one man made real headlines with fake news.

William Henry Ireland (1775-1835) grew up starved for his father’s affection. Samuel Ireland was a man who loved his collections of books, pictures, and curios far more than his family. But what he loved beyond all else was William Shakespeare. One day, in 1794, the 19-year-old William Henry sneaked into his father’s study and started looking through his Shakespeare books. He then took a sheet of paper and traced a facsimile of Shakespeare’s signature from a book. With this harmless little act, William Henry Ireland commenced his career of fabricating a series of deceptions.

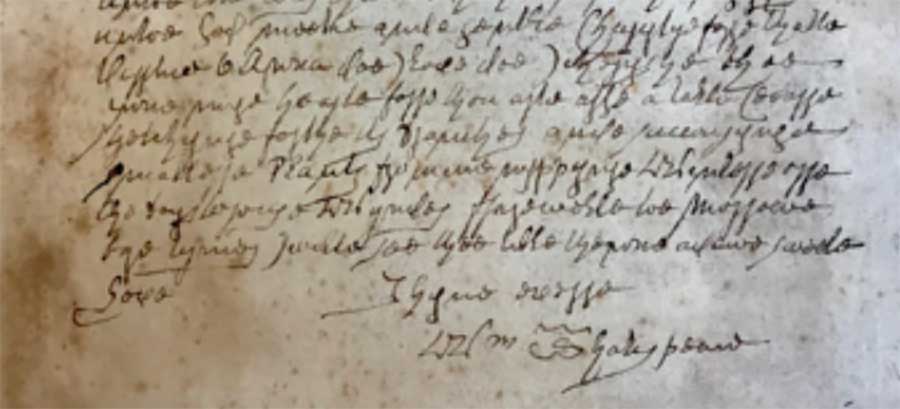

Detail of a forged letter from William Shakespeare to his wife, Anne Hathaway, in the hand of William Henry Ireland. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

In 1795, Ireland presented his father with a gift: a parchment deed signed by William Shakespeare. He told his father that a friend, whom he called “Mr. H,” had found an old trunk filled with Renaissance manuscripts and documents, many signed by Shakespeare.

Ireland continued to bring home letters Shakespeare had apparently written to famous figures of the Elizabethan and Jacobean ages; love letters written to his wife, Anne Hathaway, as well as locks of Anne’s hair; and even a document wherein Shakespeare clearly articulated his devotion to the Protestant faith. He eventually delivered manuscript drafts of King Lear and a few pages of Hamlet.

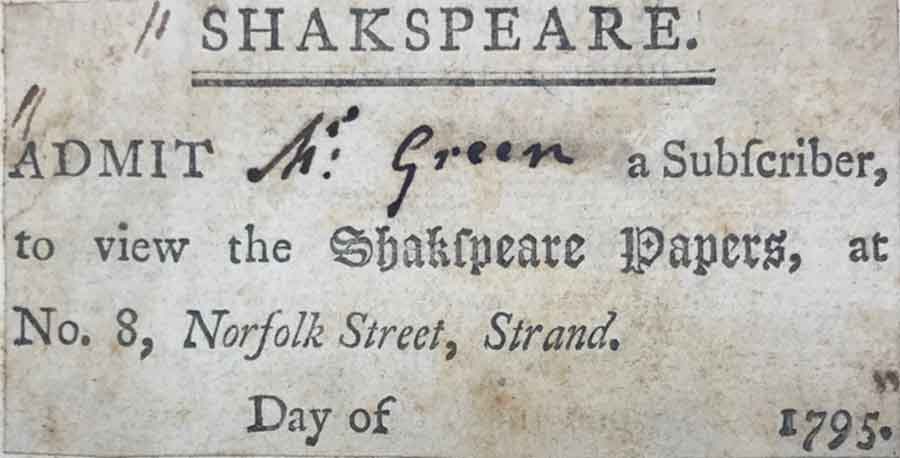

Real news of this fake discovery started circulating in London. Collectors, scholars, and actors flocked to the Ireland residence to view these extraordinary treasures. The demand to see these items grew so large that the family started issuing tickets to control the crowds.

Admission ticket to the Ireland home. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

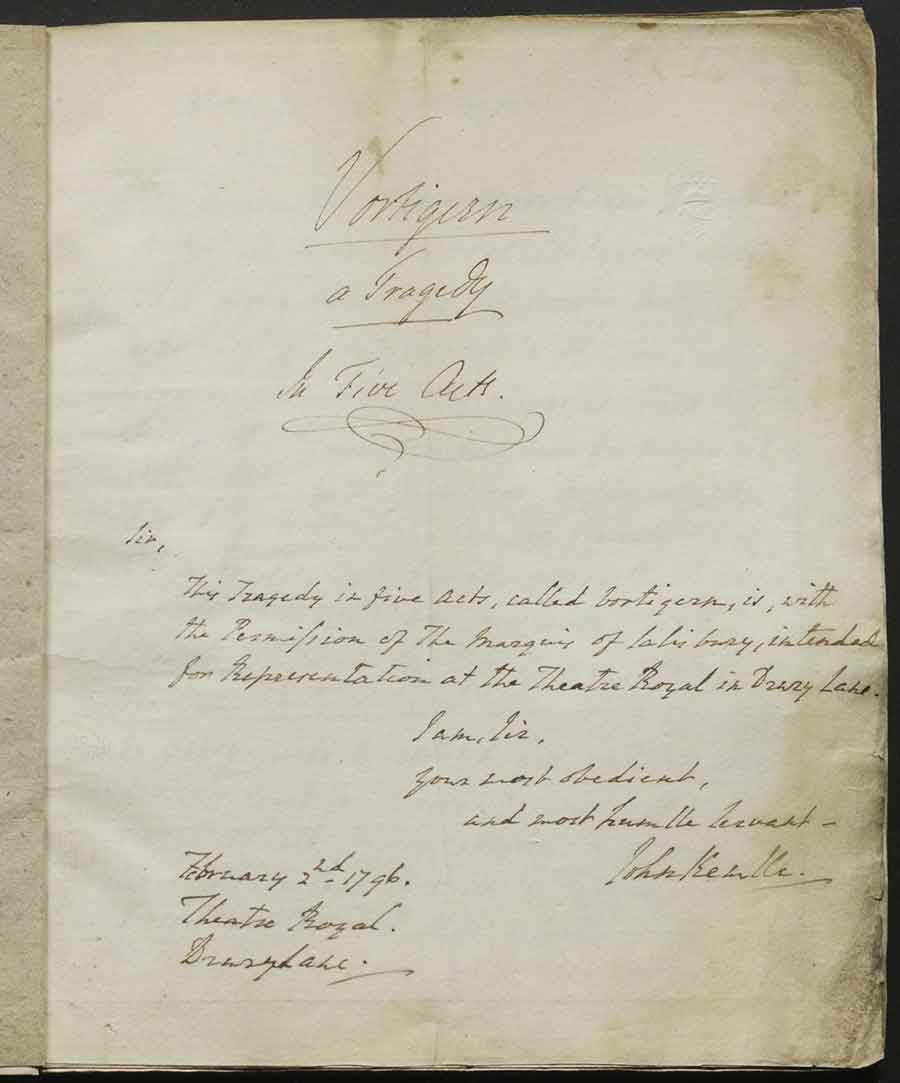

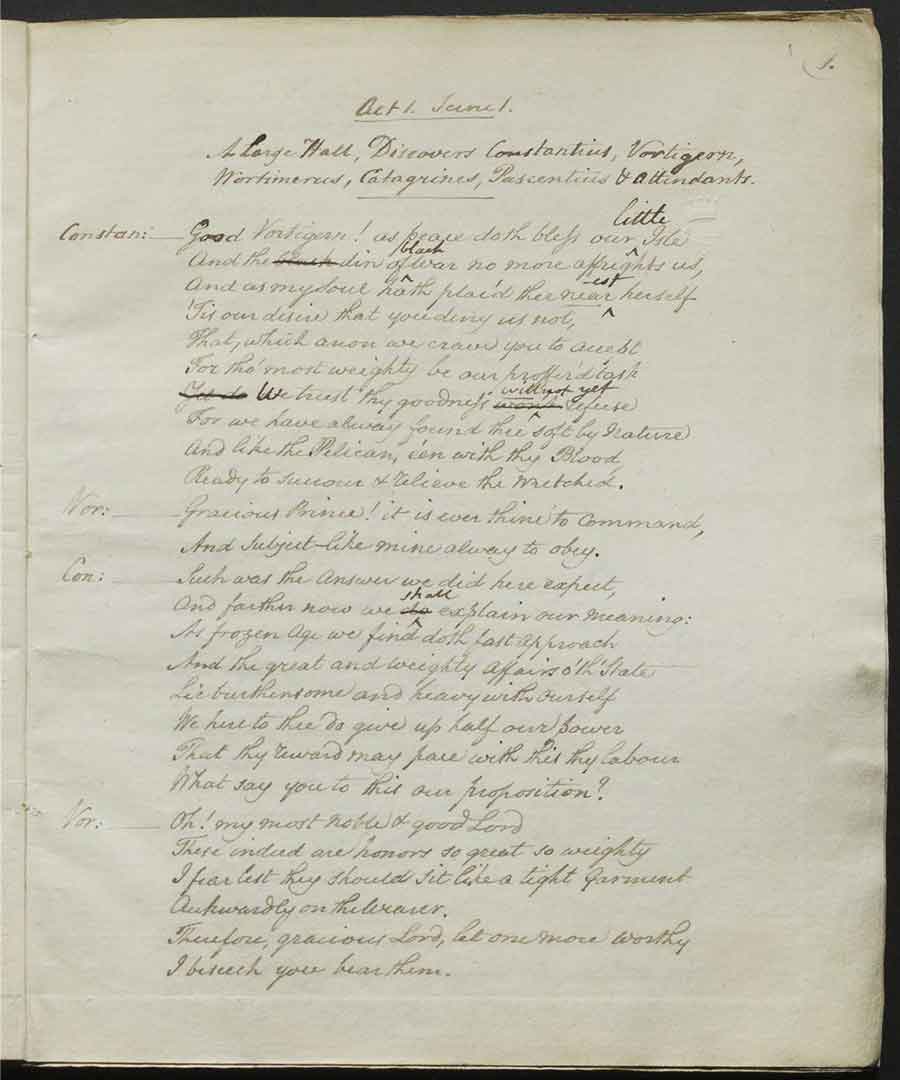

Within months, London newspapers were publishing essays arguing for or against the authenticity of the items, and satirical pamphlets and prints that defended or mocked the Irelands’ manuscripts began to circulate. William Henry, already fueling a full-blown Shakespeare mania, then decided to raise his deception to a higher level. The next manuscript he unearthed was an unknown “original” Shakespeare play, a tragedy titled Vortigern.

William Henry wrote an entire five-act play, emulating his father’s beloved Bard. Just like Shakespeare, he drew inspiration from the 1577 Holinshed’s Chronicles, the iconic Elizabethan history of England and the realm, first published in 1577, which recounts the history of Anglo-Saxon and early Norman rulers. Vortigern was a brutal, usurping, fifth-century King of the Britons.

Title page of Vortigern, officially approved script submitted to Examiner of Plays John Larpent, February 2, 1796. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

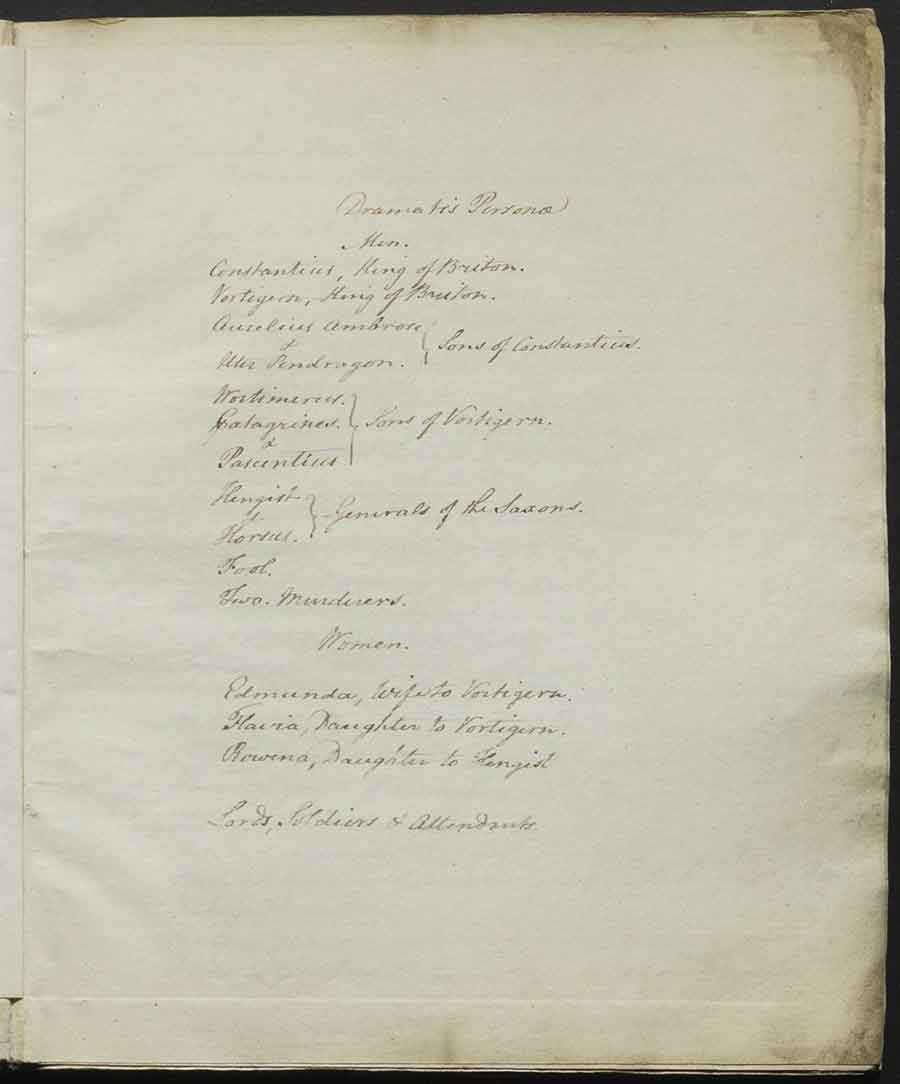

In Ireland’s play, an earlier King of the Britons offers his loyal servant, Vortigern, an opportunity to rule over some of his realm. Vortigern murders the king, and the feudal lords choose sides. Vortigern abandons his wife when he falls in love with Rowena, the daughter of one of his generals. In the end, Vortigern loses his battle against the enemy lords, but his opponents magnanimously let him live. The play is part Hamlet, part Macbeth, part King Lear, and all written by William Henry Ireland.

In the spring of 1795, the playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan decided he wanted to stage Vortigern at his theater in Drury Lane, and he hired John Philip Kemble, the renowned actor, to star in the title role. Sheridan and Kemble constantly expressed doubts about the play’s authenticity, but neither man could bear to have the opportunity slip by if there was even a slight chance that the play was real.

Dramatis personae from Vortigern, officially approved script submitted to Examiner of Plays John Larpent, February 2, 1796. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

The play was originally set to open on April 1, 1796 (April Fool’s Day), but Sheridan thought that was a little too on the nose and decided to move the opening performance to the following evening. He left Shakespeare’s name off the playbill, but everyone in London knew the controversy surrounding the play. A total of 3,500 tickets were sold, packing the house to full capacity!

Throughout the evening, Kemble delivered his lines in an increasingly over-the-top style, poking fun at the entire thing. At the end of the performance, he returned to the stage to announce that the play would not be performed again. Fist fights broke out in the audience between those who believed the play was by Shakespeare and those who did not. Many people must have also been simply furious at the thought that they had been duped by Ireland and the theater.

Ireland realized his deception could not be sustained, and a few months later, he confessed to forging everything. His father refused to believe his son was capable of masterminding such a hoax, but Samuel Ireland never spoke to his son again.

Beginning of Act 1, scene 1 from Vortigern, officially approved script submitted to Examiner of Plays John Larpent, February 2, 1796. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

William Henry was never charged with a crime because he never made any money from the scam. He went on to publish a full account of his hoax, a book that actually sold quite well, and he tried to ride his little wave of notoriety by going to pubs around London and selling his “famous” Elizabethan forgeries, which became quite collectable. But even this scheme never really panned out, and he died in 1835, in relative obscurity.

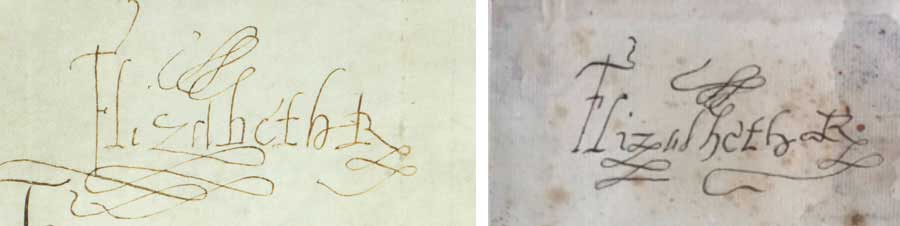

Here are two manuscripts from The Huntington’s collections that bear Queen Elizabeth I’s signature. Which one was signed by Gloria Regina herself, and which penned by William Henry Ireland?

Left: Queen Elizabeth I’s signature, October 20, 1573. Right: William Henry Ireland’s forgery of Queen Elizabeth I’s signature. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Vanessa Wilkie is William A. Moffett Curator of Medieval Manuscripts and British History at The Huntington.