The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

The Visionary and Inspiring John Ruskin

Posted on Wed., Dec. 11, 2019 by

Sir Hubert von Herkomer, John Ruskin, 1879, watercolor. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

During his lifetime, John Ruskin (1819–1900) was acknowledged as one of the 19th century's greatest geniuses, his books and lectures excitedly awaited and intensely applauded after their publication. It is also the case that, during the second half of his career, John Ruskin was reviled as one of his century's great troublemakers, his books and lectures either shunned like the plague or damned after their publication. It is partly because of the lamentable durability of this second reputation that we know so little of Ruskin today.

To make the case for Ruskin’s continuing relevance, despite his undeserved obscurity, I am convening a conference titled “John Ruskin, 19th-Century Visionary, 21st-Century Inspiration” in Rothenberg Hall on December 13 and 14, 2019—during the last month of a year that has marked the 200th anniversary of Ruskin’s birth.

A group of scholars and artists from the United Kingdom, Europe, and North America—each an expert in various aspects of Ruskin’s work—will attest to the importance of reviving Ruskin’s ideas in our troubled time.

Our contemporary lack of awareness of Ruskin and his revolutionary works is most unfortunate, first because all but a handful of his books are literary masterpieces, and, second, because his works of social criticism brim over with a series of recommendations which, if we ever took them seriously, would make our lives remarkably happier and healthier.

As instances, consider the little-known fact that Ruskin was one of the first environmentalists, arguing passionately against the destruction of nature and its beauties by the juggernaut called the Industrial Revolution. Or the fact that, in his social critiques, he contended for the relief of the suffering of the poor and pressed for creating an honest and customer-centered system in which the goal of economic life would be not individual profit but the betterment of all.

John Ruskin (British, 1819–1900), Geneva from the Rhone, undated, 1842 or 1846, watercolor, graphite pencil, and colored chalk on wove blue paper. Gilbert Davis Collection. This work is on view in the exhibition "John Ruskin and His 'Frenemies'" in the Huntington Art Gallery's Works on Paper Room through Jan. 6, 2020. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

He began as an art critic, virtually inventing the role in a series of books published in the 1840s and 1850s—the manuscripts of some of the most important, including The Seven Lamps of Architecture, Lectures on Architecture and Painting, and The Two Paths, are preserved at The Huntington. His eloquent writings made J. M. W. Turner into the most famous landscape painter in the world and turned the group of artists known as Pre-Raphaelites into applauded new masters. Other works extolling the beauties and historical significance of Venice, Florence, and the Alps single-handedly put these wonders, then much neglected, back on the world cultural map.

He was also a remarkably skilled artist, as this beautiful image of Geneva from the bank of the Rhone, drawn in 1845, shows. This drawing, as well as works by Turner and the Pre-Raphaelites (all part of The Huntington’s collection), are now on display in an exhibition titled "John Ruskin and his 'Frenemies'" that is on view on the second floor of the Huntington Art Gallery through Jan. 6, 2020.

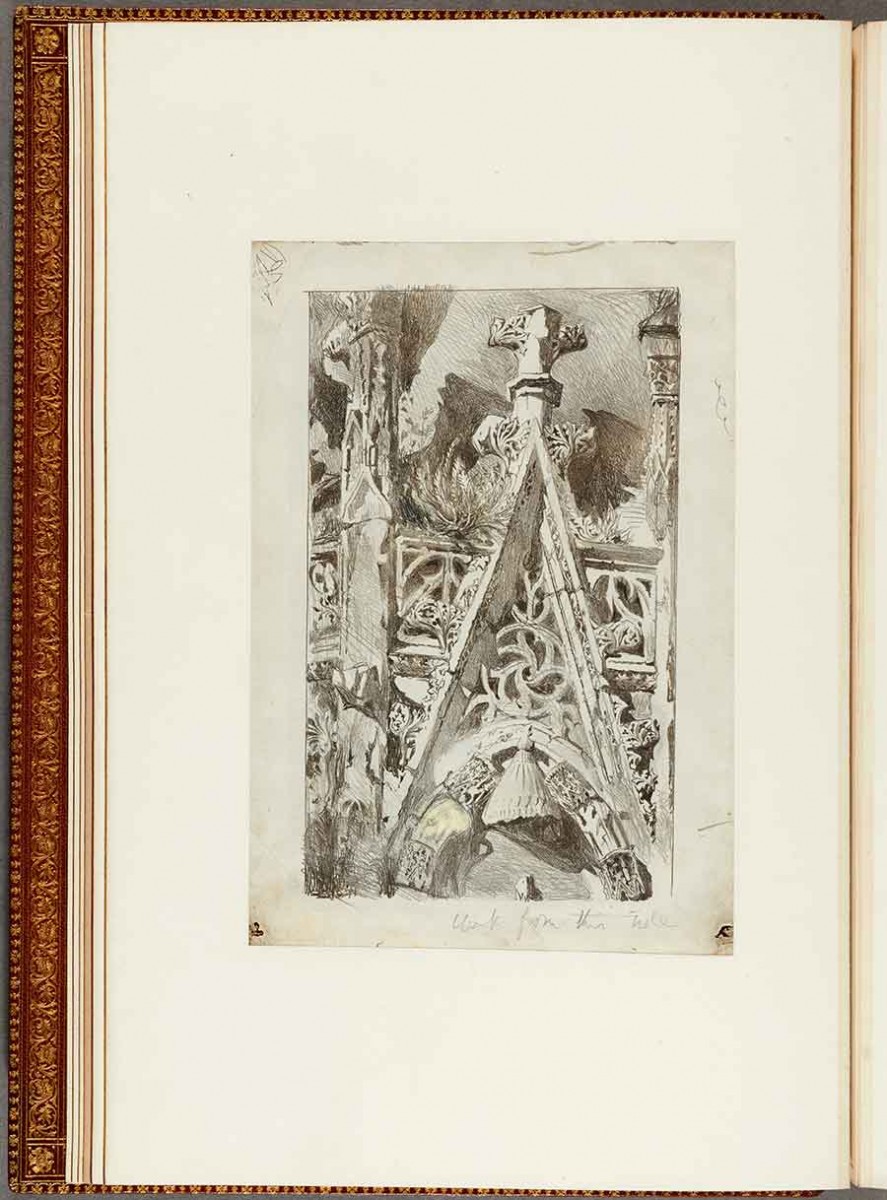

It was Ruskin’s unrelenting criticism of the inhumanities created by capitalism that got him into trouble. His study of architecture had taught him that everyone involved in the creation of buildings had an invaluable creative impulse, an impulse usually overlooked, to the detriment of both the individual and society—a creative spirit clearly evidenced in Ruskin’s drawing of a portion of the façade of the Cathedral of Saint-Lô in northern France.

The problem, he said in Unto this Last (a portion of this manuscript is preserved at The Huntington), the book he always believed his most important, was that the employees of most businesses were essentially regarded as tools, a dubious status that allowed employers an excuse to underpay or mistreat them while they pocketed the money thus “saved.” The argument made the business moguls of Ruskin’s time furious. By holding their feet to the moral fire, he discovered that, almost immediately, his social critiques became objects of derision and dismissal.

John Ruskin, Façade of Cathedral of St.-Lô, Normandy (detail), 1840s, pencil on vellum, 17 1/2 x 12 1/2 in. Purchased by Henry E. Huntington, William K. Bixby Library, 1918. Ruskin made this sketch for a plate in his Seven Lamps of Architecture, 1849, a book that argues strenuously for an architectural practice guided by ideals as well as the preeminence of the gothic Revival style. This book is on view in the exhibition “Nineteen Nineteen” in MaryLou and George Boone Gallery through Jan. 20, 2020. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

In his later years, frustrated that the environmental and humane economic reforms he had hoped to stimulate were nowhere manifested, Ruskin created “The Guild of St. George,” an organization devoted to ecologically sound practices which he believed, as the Guild’s numbers grew, would transform society for the better. Today’s Guild has active branches in both the United Kingdom and North America.

For these reasons alone, it should be clear that this greatly underappreciated 19th-century master is long overdue for a reassessment that demonstrates his enduring relevance as we try to come to grips with the great aesthetic and social issues of our time.

Funding for this conference is provided by The Huntington’s Dorothy Collins Brown Endowment and The William French Smith Endowment.

Jim Spates is professor of sociology, emeritus, at Hobart and William Smith Colleges in Geneva, New York. Over the last three decades, he has written extensively about Ruskin’s life and work and, since 2013, has been the webmaster overseeing Why Ruskin, a website dedicated to showing why Ruskin is still relevant today.