The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

An Artist Obscured

Posted on Wed., Oct. 2, 2019 by

Hugo Gellert (1892–1985), Worker and Machine, 1928, oil on board, 30 1/2 x 30 7/8 inches. Collection of Sandra and Bram Dijkstra. Photo by Deborah Miller.

With his back turned to us, a mechanic is the focal point of Hugo Gellert's painting Worker and Machine (1928), currently on view in the Virginia Steele Scott Gallery of American Art. Black oil paint that imitates lithographic crayon highlights his broad shoulders, thick arms, and streamlined physique, revealing his role as a strong laborer. His oversized hand clasps a wrench, communicating his readiness to fix whatever problem the machine before him presents. The simple rendition of a factory worker with basic colors, geometric forms, and an uncluttered composition shows Gellert's talent as a Modernist artist. But this picture is deceptively simple, contrasting with Gellert's complex life as a painter, lithographer, and political activist—an artist forgotten because of his leftist views.

Born in Budapest in 1892, Gellert immigrated to the United States at the age of 15. By age 17, he enrolled in the National Academy of Design in New York City, where he studied painting and lithography, winning prizes for his etchings. Around this time, his younger brother Ernest became a Socialist activist, influencing the artist’s own politics. When both Ernest and a cousin died in World War I, Gellert transitioned to Communism, openly promoting his beliefs as his brother had before him. He said: “Being a Communist and being an artist are two cheeks of the same face and, as for me, I fail to see how I could be either one without also being the other.”

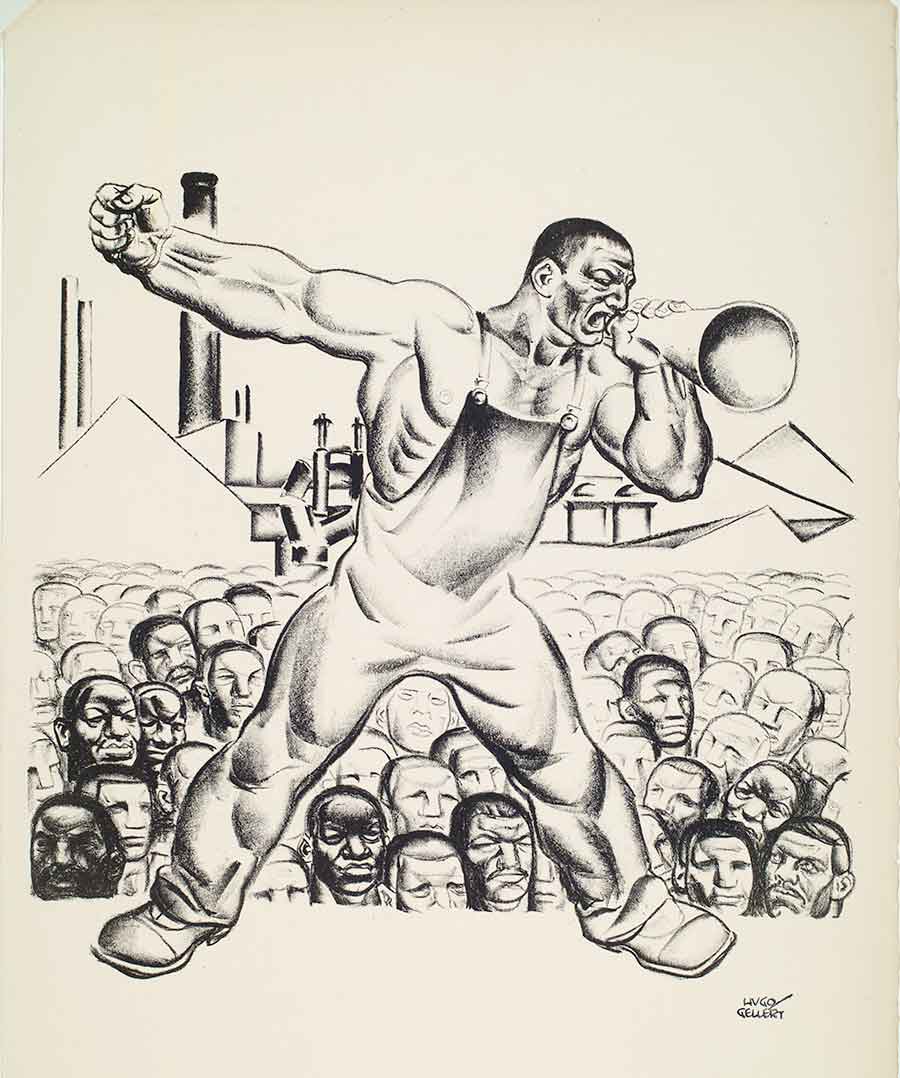

Hugo Gellert, Primary Accumulation 19, 1933. © Hugo Gellert; Courtesy of the estate of the artist and Mary Ryan Gallery, New York. Lithograph, 15 x 14 in. (38.1 x 35.6 cm.). This drawing exemplifies Gellert’s simple style. The outline of the central figure forms a star, cleverly alluding to Gellert’s Communist beliefs.

Gellert started teaching art at the progressive Stelton Modern School in New Jersey, whose founders shared his anti-capitalist views. Influenced by the children he instructed, Gellert believed the purest art was simple and thus stuck to basic colors, shapes, and compositions in his work.

Gellert also became involved in editing and illustrating New Masses, a Communist publication. He and other artists from New Masses organized the John Reed Club, with the main goal of supporting Marxist writers and artists who believed that “Art is a weapon in the class struggle.” The club and its many local chapters disbanded in 1936, however, at the suggestion of the American Communist Party, which believed that the increasing power of fascist leaders abroad called for a club that could unify a broader spectrum of people under a larger banner than Communism. Out of this dissolution sprang the pan-ideological American Artists' Congress.

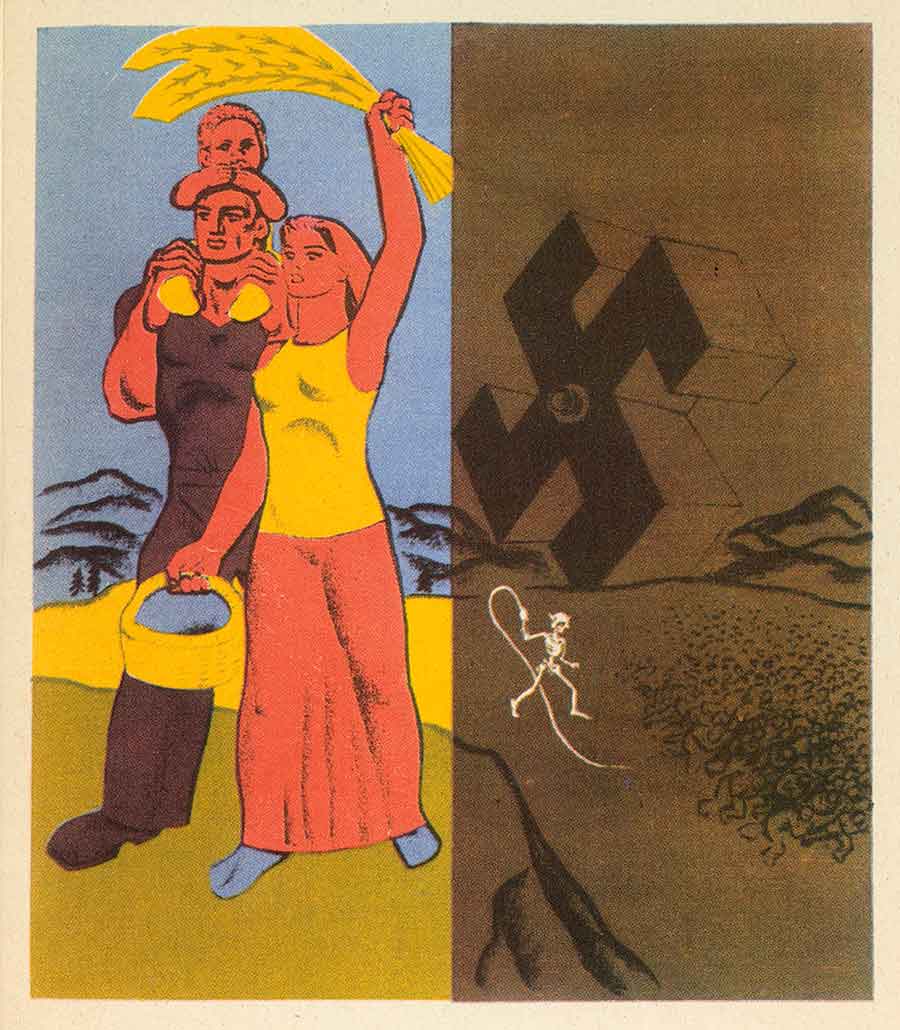

Hugo Gellert, Free World or Slave World from Century of the Common Man, 1943. © Hugo Gellert; Courtesy of the estate of the artist and Mary Ryan Gallery, New York. Gellert contrasts the idealistic propaganda that the Third Reich produced and the reality of fascism.

The former members of the John Reed Club sought to unite artists of all styles and beliefs in opposition to fascism, which was on the rise as the Weimar Republic in Germany was transitioning to the Third Reich. Such artists as George Ault, Harry Gottlieb, Eitaro Ishigaki, Louis Lozowick, Moses Soyer, Harry Sternberg, and Max Weber joined the Congress, exemplifying the diversity of art styles and beliefs the Congress hoped to encompass. Gellert joined the Congress as well, becoming part of the de facto leadership alongside Weber, the official chairman. Recognizing the threat of visual propaganda perpetrated by Nazi Germany, the Congress believed that art could be used as a weapon against fascism. At the first meeting of the Congress in 1936, member Lewis Mumford suggested that artists could incite a dictator’s worst fear—criticism—with their freedom of expression. The Congress agreed and additionally desired to use art to unite two social groups: artists and workers. Gellert explained at the same meeting why this partnership was important, stating at first: "The major objective of our Congress is to take a stand against Fascism and War." He also declared: "Labor is the greatest organized body in the country. In it we find our most reliable and most powerful ally against Fascism." However, it was not just laborers’ numbers, but their indispensability that made them one of the best forces against fascism, as Gellert explained in the same speech: “… social forms and social classes may rise and disappear, labor remains indispensable as long as life itself exists . . . To be isolated from the worker is to be isolated from the only vital, progressive force in society today.” In addition to fighting fascism abroad, the Congress opposed injustice at home. Members called for an end to discrimination against minorities and supported the Costigan-Wagner Bill, an anti-lynching law.

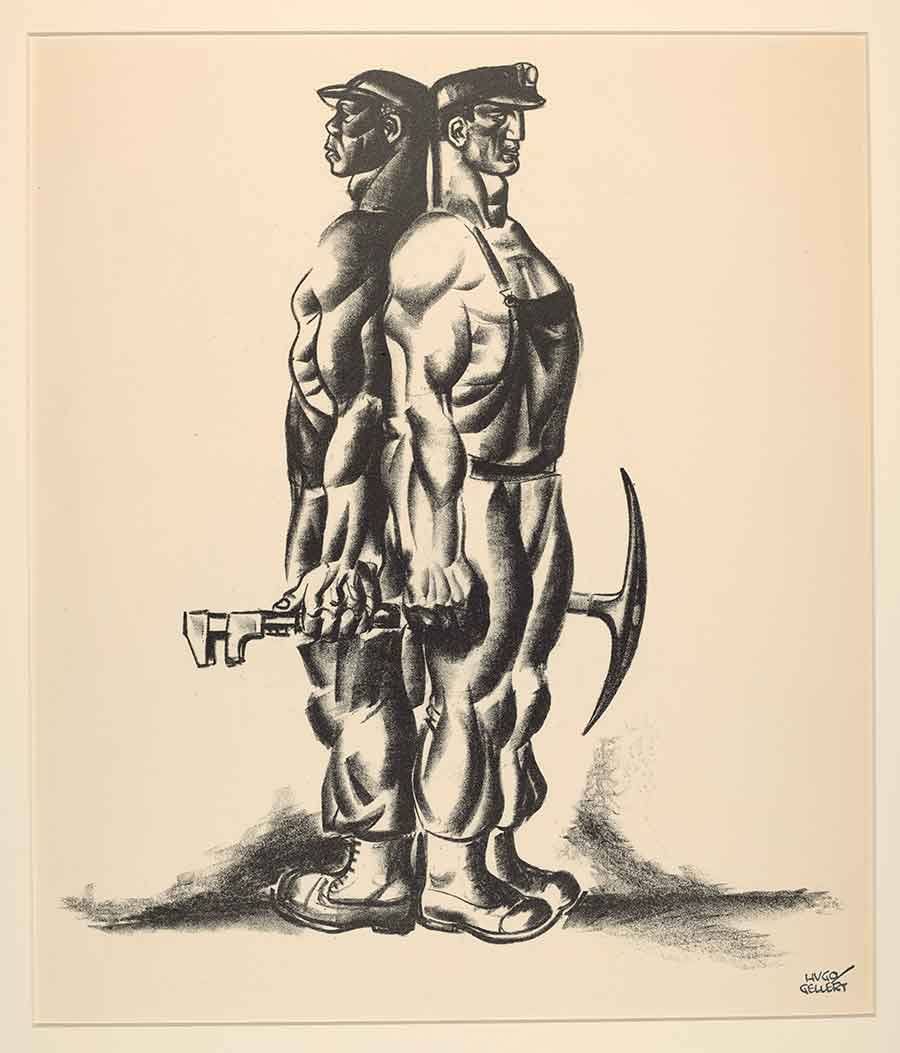

Hugo Gellert, The Working Day 37, 1933. © Hugo Gellert; Courtesy of the estate of the artist and Mary Ryan Gallery, New York. Lithograph, 22 5/8 x 15 3/16 in. (57.5 x 38.6 cm.). This image highlights Gellert’s lithographic talent and reflects his advocacy of racial equality and solidarity.

Worker and Machine is not only eye-catching and Modernist, but also exemplifies Gellert’s revolutionary ideology, which drew inspiration from children, exalted the laborer, and called for social change in the face of fascism. Unfortunately, Gellert’s Communist beliefs collided with subsequent U.S. opposition to the U.S.S.R. after World War II, causing him to fall into obscurity. Murals painted by Gellert in New York City during the 1930s were torn down, and his name was soon forgotten. (In contrast, other Communist artists of the time, such as Diego Rivera, are still remembered.) Ultimately, Hugo Gellert’s surviving lithographs and paintings are important not only as testaments to his political advocacy, but as reminders of a congress of artists who recognized fascism’s threat in the 1930s and had the courage to face it head on.

Lauren Rodriguez is studying art history at the University of California, Los Angeles, and has served as a Getty Marrow Undergraduate Intern in the American art division of The Huntington.