The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Utopia is Nowhere

Posted on Tue., Sept. 10, 2019 by

Artist, designer, writer, and educator Rosten Woo has been delving into the papers of Robert V. Hine (1921–2015), a scholar of the American West whose research focused on utopian communities in California. Photo by Kate Lain.

In January 2019, The Huntington announced that it was partnering with the Los Angeles arts organization Clockshop for the fourth year of The Huntington's /five initiative, inviting noted artists and writers to create new work by engaging with The Huntington's collections. A part of The Huntington's Centennial Celebration, which runs from September 2019 to September 2020, the 2019 /five project uses Thomas More's Utopia (1516) as a thematic point of departure. The project will culminate in the exhibition "Beside the Edge of the World," on view at The Huntington from Nov. 9, 2019, to Feb. 24, 2020, which will include The Huntington's copy of the first edition of More's Utopia in Latin.

Carribean Fragoza, a freelance journalist who writes about art in Southern California, Vanessa Wilkie, the William A. Moffett Curator of Medieval Manuscripts and British History at The Huntington, and artist, designer, writer, educator, and /five participant Rosten Woo sat down to discuss More’s Utopia and Woo’s desire to create artistic works that help people reorient themselves to place.

Rosten Woo (left), William A. Moffett Curator of Medieval Manuscripts and British History Vanessa Wilkie (center), and freelance journalist Carribean Fragoza (right) met at The Huntington to discuss Thomas More’s Utopia (1516) and Woo’s desire to create artistic works that help people reorient themselves to place. Photo by Kate Lain.

Carribean Fragoza: How were you able to engage Thomas More’s Utopia, which is not only centuries old but also feels so removed from what we imagine it to be?

Rosten Woo: I’m always surprised when I read a super old text and it turns out to be murkier and more ambiguous than a lot of texts today. It had been a long time since I last looked at Utopia. I spent some time with it recently, and it is definitely very different from what I remembered and how it is remembered generally.

Rosten Woo studies landscape drawings produced during an expedition led by John Russell Bartlett (1805–1886). Bartlett was hired in 1850 to survey the border between Mexico and the United States after the Mexican American War (1846–1848). Photo by Kate Lain.

Vanessa Wilkie: “Utopia” has come to mean a perfect society, but in More’s original text, it literally means “nowhere.” He wasn’t trying to describe a vision of perfection. More was saying that perfection doesn’t exist anywhere, but people started thinking of a utopia as a model of perfection, and that evolves over the course of centuries into, for example, what Robert Hine is looking at in 20th-century California communes, as we see in the Robert Hine Collection here at The Huntington.

Carribean Fragoza: Part of More’s imagination, even in this tremendously fantastical work of fiction, is still shaped by the project of imperialism. One of my critiques of utopic societies is that we repeatedly see them working in these imperialistic ways, implanting themselves into these territories to start fresh, new societies that aren’t new at all.

Woo has been delving into the papers of Robert V. Hine (1921–2015), a scholar of the American West whose research focused on early utopian settlements in California. He has also been studying landscape drawings produced during an expedition led by John Russell Bartlett (1805–1886). Bartlett was hired in 1850 to direct the survey of the border between Mexico and the United States after the Mexican American War (1846–1848). Woo is interested in how utopian communities were formed and funded, and in exploring the relationships between “utopias” and the outside world.

John Russell Bartlett hired artists such as Henry B. Brown to accompany his expedition through the borderlands between Mexico and the United States. In this view of the Grass Valley region of northern California, Brown depicts a man on horseback on one side of a river and a camp with a couple of teepees on the other side. Woo sees in it both beauty and a reminder of what will be destroyed. Photo by Kate Lain.

Rosten Woo: One of the things I found very interesting is how porous More’s utopia is. Utopias are not necessarily as insular as we think they are. One of the things that I like about Robert Hine is that he’s an optimistic scholar and is more interested in communitarian aspects of utopias. He notes that, while a community, like the Little Landers [small-scale cooperative farmers in California], might fail, the people that he talks to describe their time in the commune as the best years of their lives. You have to think about the scale on which we judge whether something succeeds or fails.

When I started looking at Hine’s papers and pamphlets of all the communities, I found his research files about John Russell Bartlett, a bookseller, ethnographer, and esoteric philosopher who got appointed to survey the U.S.-Mexico border. He spent three years wandering the area and was totally unprepared for the work. He also wandered off into other places, like San Francisco. Eventually Bartlett was fired for drawing the borderline too far north. Robert Hine had this mission to resuscitate Bartlett’s reputation and wrote a book about him and his journeys.

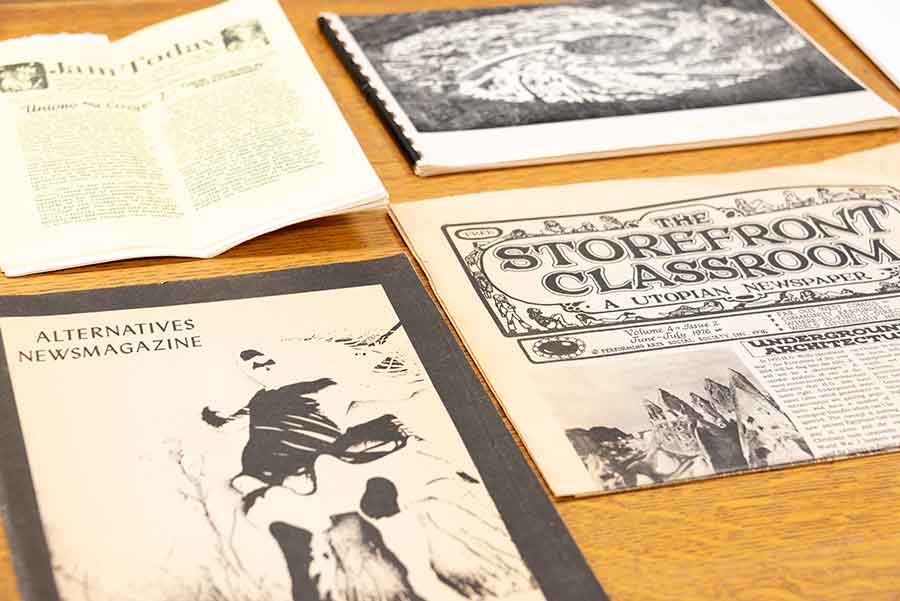

Publications collected by Robert V. Hine (1921–2015), a scholar of the American West whose research focused on utopian communities in California. Photo by Kate Lain.

In looking through the collection, I was interested in boundaries, including political boundaries, and the kinds of practical and theoretical problems they bring up. It was really interesting to see how an abstract idea gets translated on the ground. For a good 50 years after the U.S.-Mexico boundary was drawn, they had to redraw the line every three years and set markers along it, though now it’s pretty clearly delineated and militarized. So, it’s really easy to draw the line but really complicated to make it mean something.

As a surveyor, Bartlett was trying to make an abstract thing a reality. He also hired artists to go along with his expedition. He and the artists were capturing the world and things that were fascinating to them in watercolors and drawings, but the images also had real and disastrous implications for the people and things in the expedition’s path. There’s this pencil drawing that I find really moving: On one side of the river is a man on a horse, and on the other is a camp with a couple of teepees and smoke rising from a fire. It’s a beautiful image but also conveys a sense of foreboding because, in the act of conquest and producing encyclopedic knowledge, so much is about to be destroyed.

Carribean Fragoza: Did you find anything in the Hine collection that surprised you or that you didn’t expect?

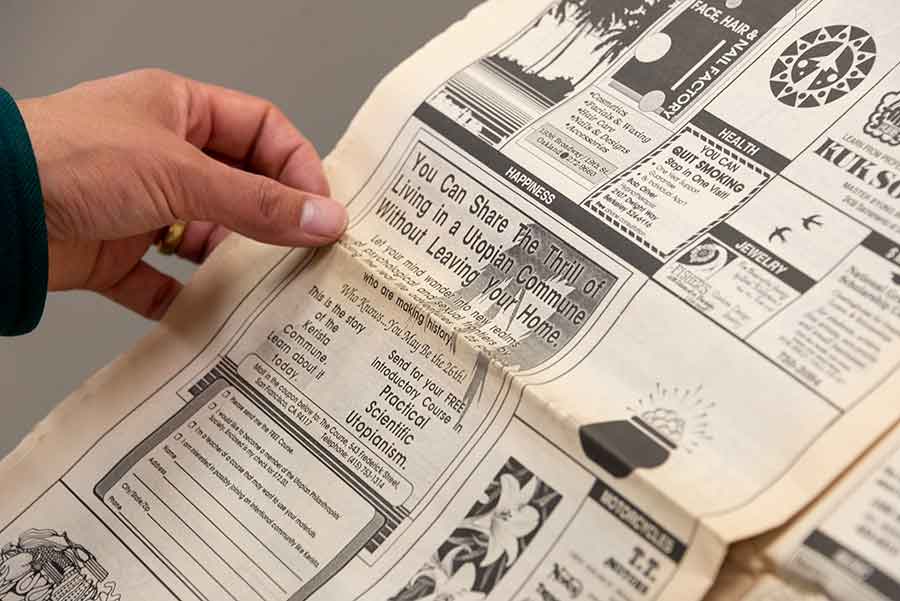

Woo reads an advertisement for a utopian commune in a newspaper from the Robert Hine Collection. Photo by Kate Lain.

Rosten Woo: I was surprised by how much cross-commune communication took place and how much people were trying to share their practices with each other. Instead of trying to insulate themselves and becoming a cult, there was a huge network of communes that shared techniques in these publications. One of the stereotypes of utopia is that their members were trying to create all the rules up front and get everyone to subscribe to them. But, in California, the majority of them tried to figure out rules as they went along. In the 1970s, more than one million people were living in experimental communities, and many people were trying to figure out how to live in a way that they thought was valuable. It’s amazing to think how many people were that dissatisfied with the world.

It reminds me of this quote from Henry George, one of the great American leftist thinkers of the 19th century, who said, “There are people into whose heads it never enters to conceive any better state of society than that which now exists.” The publications in the Robert Hine Collection tell the story of how utopias aren’t just these insular things but are really spaces for experimentation—and a lot of people really got a lot out of that.

Rosten Woo's contribution to the upcoming /five exhibition consists of five audio tours that guide visitors through The Huntington's grounds as well as a short animation of illustrations on view in the exhibition gallery. Woo's audio tour takes listeners through stories from Robert Hine's research: to the U.S.-Mexico border; to Kaweah Colony, a utopian commune in Northern California; and into the Chinese Garden.

Carribean Fragoza is a freelance journalist who writes about art in Southern California.