The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Exploring the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine

Posted on Fri., Aug. 23, 2019 by

Participants in The Huntington’s first residential summer institute in the history of science, technology, and medicine gather around Daniela Bleichmar, professor of art history and history at the University of Southern California, to take a close look at some of the Library’s visual resources regarding natural history and Latin America. Photo by Lisa Blackburn.

In June, 16 eager participants from around the globe arrived for the inaugural Huntington residential summer institute in the history of science, technology, and medicine. The program, part of the newly launched Caltech-Huntington Advanced Research Institute in the History of Science and Technology, was designed to provide participants with a materials-based experience anchored in The Huntington's collections throughout 10 days of seminars and hands-on sessions with books, manuscripts, prints, photographs, and much more.

Daniel Lewis, Dibner Senior Curator of the History of Science and Technology at The Huntington, discusses the Library materials on view with summer institute participants. Photo by Lisa Blackburn.

The institute included graduate students in history, history of art, and history of science and technology, as well as a number of early career scholars. Led by myself and Huntington curators Daniel Lewis and Joel Klein, and featuring several guest speakers, the group explored how to make sense of different copies of the same rare book, how to use manuscript material in context with other related holdings, and how to incorporate ephemera, photographs, and visual material into our scholarship.

We also learned some of the rationale for making and archiving collections as well as the historical quirks that lead to their preservation. Every morning saw us enthusiastically engaging with a wide range of material from across the collections. Although science, technology, and medicine sound rather specialized, we found remarkable material in every corner of the Library: horse breeding records, William Morris designs, engravings of chimpanzee dissections, pictures of engineers, pre-Columbian honey bee cultivation, narratives of mental maladies, and the movement of gemstones around the world, to mention only a few.

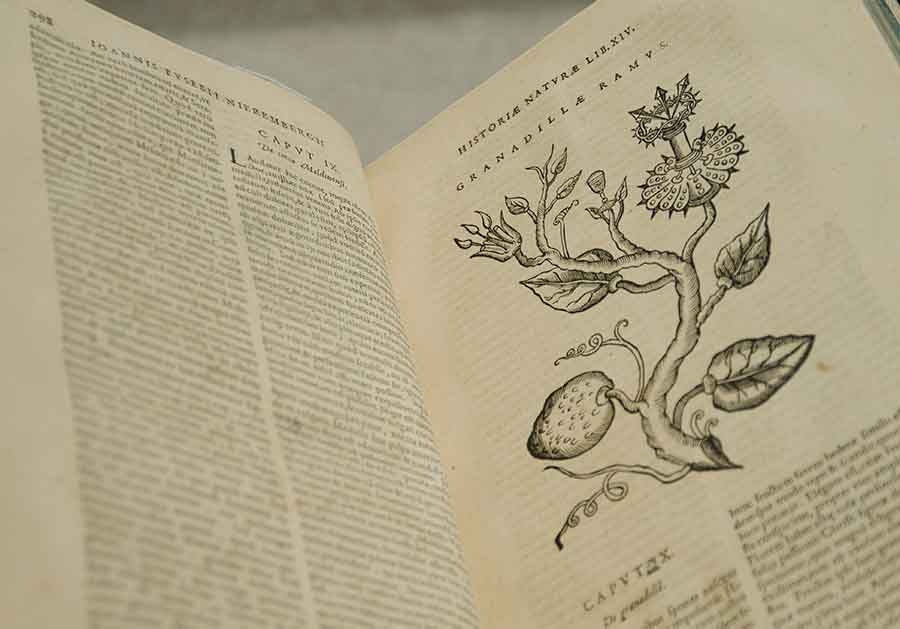

Passionflower, woodcut, in Juan Eusebio Nierenberg’s Historia naturae, maxime peregrinae, Antwerp, 1635. Photo by Lisa Blackburn.

One important theme was how best to use written and printed materials as evidence for historical arguments and how to describe the social and technical worlds in which they were created. Early on, we looked at a 15th-century Middle English medical manuscript (Huntington Manuscript 1336), written by a Cambridge law student. Many of the questions that arose as we examined it in small groups revolved around what it could tell us about the socioeconomic factors that dictated its production and use. How did medical information move from one language, and reader, to another? Who made that movement possible, and who benefitted from that translation? What can books, as material objects, tell us about their own history, and about the priorities of their users? These questions proved to be a running theme as we moved forward through the seminar sessions. We also learned to think about the role of indigenous voices and experiences in history, and how we write the history of cultures or artifacts that have been destroyed.

Another highlight was Daniel Lewis talking us through the process of finding things in the Library catalog. We were helped enormously by the Library’s curators, our guest Peter Collopy (the university archivist and head of special collections at Caltech), and invited speakers Peter Mancall, Susanna Berger, and Daniela Bleichmar (all professors at the University of Southern California).

A summer institute participant snaps The Great Water Lily of America, 1854, a chromolithograph by John Fisk Allen (1785–1865). Photo by Lisa Blackburn.

One big bonus was that the residential institute also provided ample time for participants to pursue their own research projects in the reading rooms. We felt hugely privileged to be able to explore the collections so deeply. In and around the bookish part of the institute, we also enjoyed time in the quiet of the Desert Garden. This tranquility was a stark contrast to the boisterous Tuesday afternoon coffee klatch, another rite of passage into research at The Huntington. One afternoon we had a guided tour of the Japanese Garden, its history explained layer by layer, showing us how to include landscape in our historical understanding of the past. Taken altogether—the seminars and research opportunities, the riches of the Library’s collections, the camaraderie, and the beautiful setting—the institute was an exceptional experience that we all value and remember.

Support for the Caltech-Huntington Advanced Research Institute in the History of Science and Technology has been provided by a generous gift from Stephen E. Rogers, a member of The Huntington’s Board of Governors and president of the Caltech Associates, a support group of the university.

Janet Browne is Aramont Professor of the History of Science at Harvard University and was the 2017–18 Dibner Distinguished Fellow in the History of Science and Technology at The Huntington.