The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Evidence of Pouncing in 17th-Century Print

Posted on Wed., July 31, 2019 by

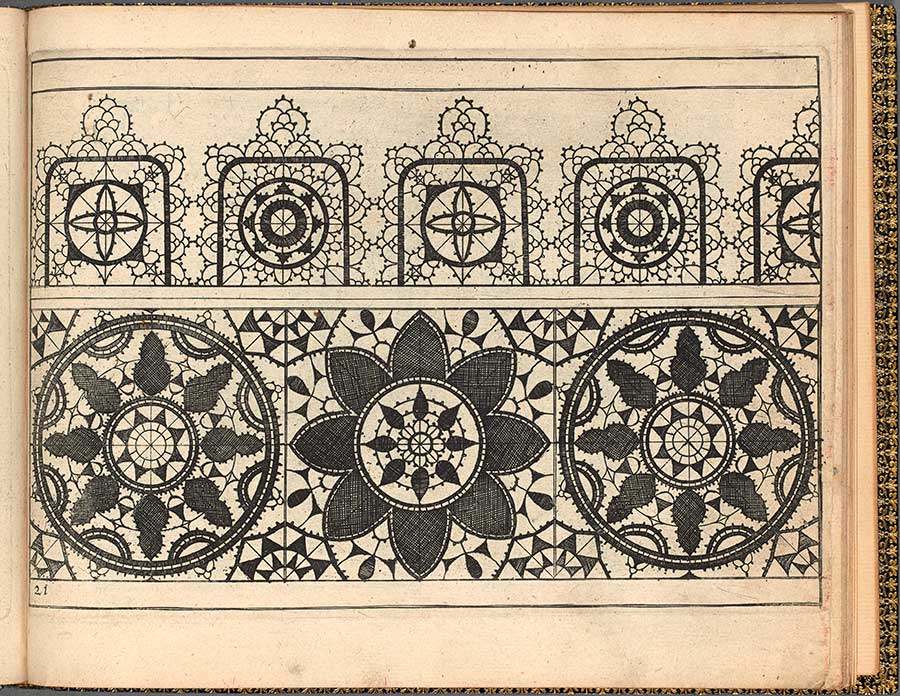

John Taylor, The Needles Excellency, London: Printed for James Boler, 1634, plate 21 recto. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Early modern readers left their marks on the printed page in many ways: They wrote annotations or drew manicules (☞) to highlight passages. Yet other interactions with the page often go unnoticed, in part because they are difficult to see or because they imply uses other than reading. For instance, two books in The Huntington's collections reveal another sort of literacy: They hold evidence of the pinpricks of needles through printed illustrations, a process known as "pouncing," that was used to copy images to other surfaces, such as cloth.

Indeed, these pinpricks in early modern books can be marks left by women who have used a needle to transfer images to linen for embroidery projects. After pricking holes to trace an image, women could use pin-dust or pounce (a powder used to treat paper before writing) to dust through holes in the page, leaving the shape of the selected pattern on linen underneath.

Pouncing can be found in embroidery manuals from the early modern period. For instance, in The Huntington copy of The Needles Excellency (1634), a collection of 32 needlework patterns prefaced with verses by John Taylor (1578–1653), has scores of minuscule, almost-invisible holes on multiple pages that show where a reader has traced images to reproduce them in another media.

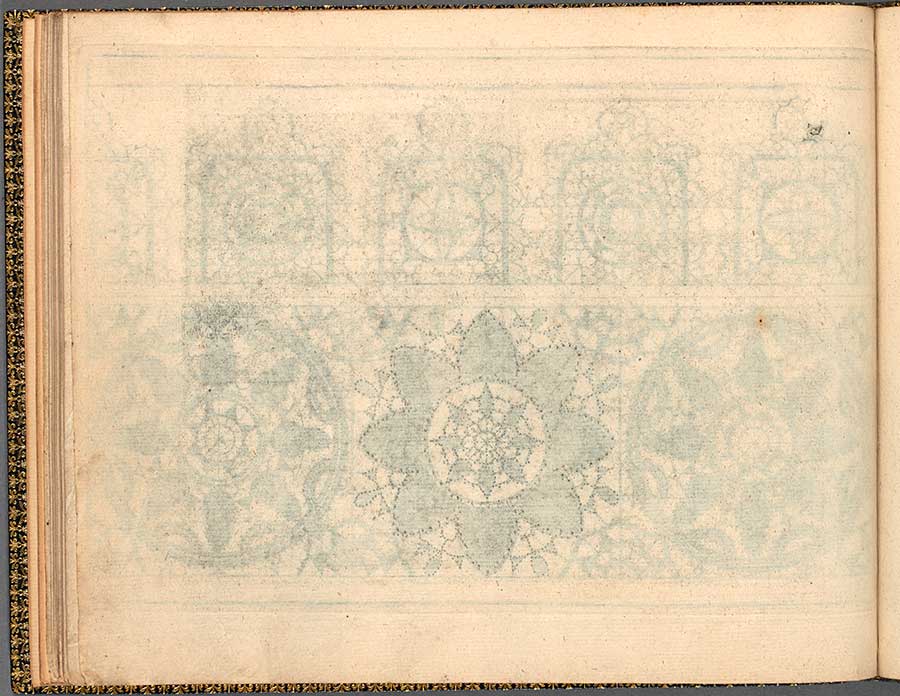

Pinpricks of a needle used to outline a floral image are clearly visible on the verso side of a page of patterns. John Taylor, The Needles Excellency, London: Printed for James Boler, 1634, plate 21 verso. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

These marks are often unintelligible on the recto, which is the right-hand page of an open book. Copper engravings, a relatively new print technology in the early 17th century, allowed for fine lines but had to be rolled through a specialized kind of press. Woodblocks, while typically less detailed, could be used on the same press as moveable type and therefore appear on the front and back of the page, sometimes alongside text.

By contrast, pattern books with copper engravings often include only illustrations on the recto. Fortunately, this means that the subtle holes left by needles are more visible on the other side of the page that is frequently left blank, known as the verso.

The tiny holes of needle pricks provide evidence of women’s work, book use, and the circulation of visual media. They also help us to reframe narratives about emerging scientific illustrations based on observations when evidence of pouncing appears in printed books; in my doctoral thesis, I am using evidence such as this to demonstrate the surprising links between women’s writing, textual media, and emerging scientific practices in the 17th century.

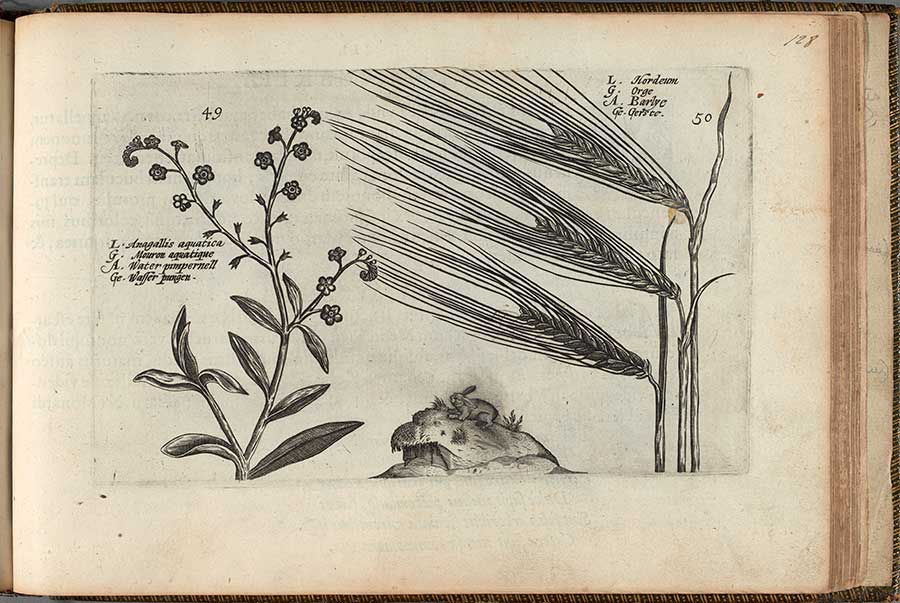

Residual pin-dust or pounce (a powder used to treat paper before writing) appears around a small image of a rabbit. The pounce passed through needle holes that outlined the shape of the rabbit, transferring the image to linen underneath. Crispijn van de Passe, A garden of flowers, Utrecht: by Salomon de Roy, for Crispian de Passe, 1615, page 128 recto. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

One case appears in Crispijn van de Passe the Younger’s Hortus floridus, or Garden of flowers (1615), which can be considered a florilegium (a kind of anthology or gathering of flowers of rhetoric) in the most literal sense—it is a collection of floral illustrations. Van de Passe emphasizes on his title page that he designed his illustrations from live specimen and includes in his book portraits of Rembert Dodoens and Carolus Clusius, both 16th-century botanists. His book, then, was designed for artists, but also for botanical study, touting detailed images that develop knowledge about Old and New World flora. In addition to framing his designs as participating in nascent observational science, van de Passe draws from ancient and contemporary natural histories for the Latin text facing some of the illustrated pages. Next to the illustrations, Latin, German, French, and English names for plants suggest an international audience that desired to learn about plants.

The floral illustrations inspired users to trace with pencil, emulate in pen, and, in some cases, pounce with a needle, revealing many ways early moderns interacted with beautiful, but also practical, designs. For instance, in The Huntington’s copy, one reader has sampled from a page depicting water pimpernel and barley. On the recto, a small rabbit appears to be surrounded by a cloud of dust.

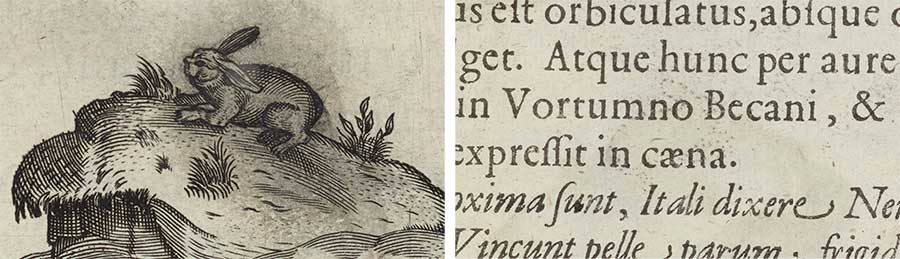

Left: Detail of Crispijn van de Passe's A garden of flowers, Utrecht: by Salomon de Roy, for Crispian de Passe, 1615, page 128 recto. Right: Pinpricks above the "o" in the word "Vortumno" outline the ear of the rabbit on the verso side of the page. The outline of the rest of the rabbit can be discerned amid the Latin text. Detail of Crispijn van de Passe's A garden of flowers, Utrecht: by Salomon de Roy, for Crispian de Passe, 1615, page 128 verso. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The verso features Latin text for the next facing page of violets and oranges, and faintly through a passage about the health benefits of the citrus fruit, a pricked rabbit emerges. Because the printed text is on the versos of copper-plate illustrations, these pages went through two different kinds of presses: the high-pressure rolling press and the moveable-type press. This pricked rabbit marks where a reader, most likely a woman, sampled from a page that includes text analogous to passages from herbals and natural histories from the period.

Pouncing in books is a reminder of the range of literacies. Books were used by a broad audience, and whether or not an embroiderer read the Latin she encountered as she sewed, she could study the shape of flora and fauna by copying printed illustrations into a new medium. Needle pricks lend insight into the circulation of visuals in a variety of materials, including forms transferred by women to household linens and clothing. Such readers’ marks also represent the burgeoning demand for lifelike pictures in print. Moreover, evidence of prick-and-pounce shows a way of seeing and sampling that not only ran adjacent to, but participated in, early observational science.

Mary Learner is a doctoral candidate in the department of English and Comparative Literature at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a 2018 Fletcher Jones Foundation Fellow at The Huntington.