The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Stereotypes and Stereotyping in the Early Modern World

Posted on Wed., April 17, 2019 by and

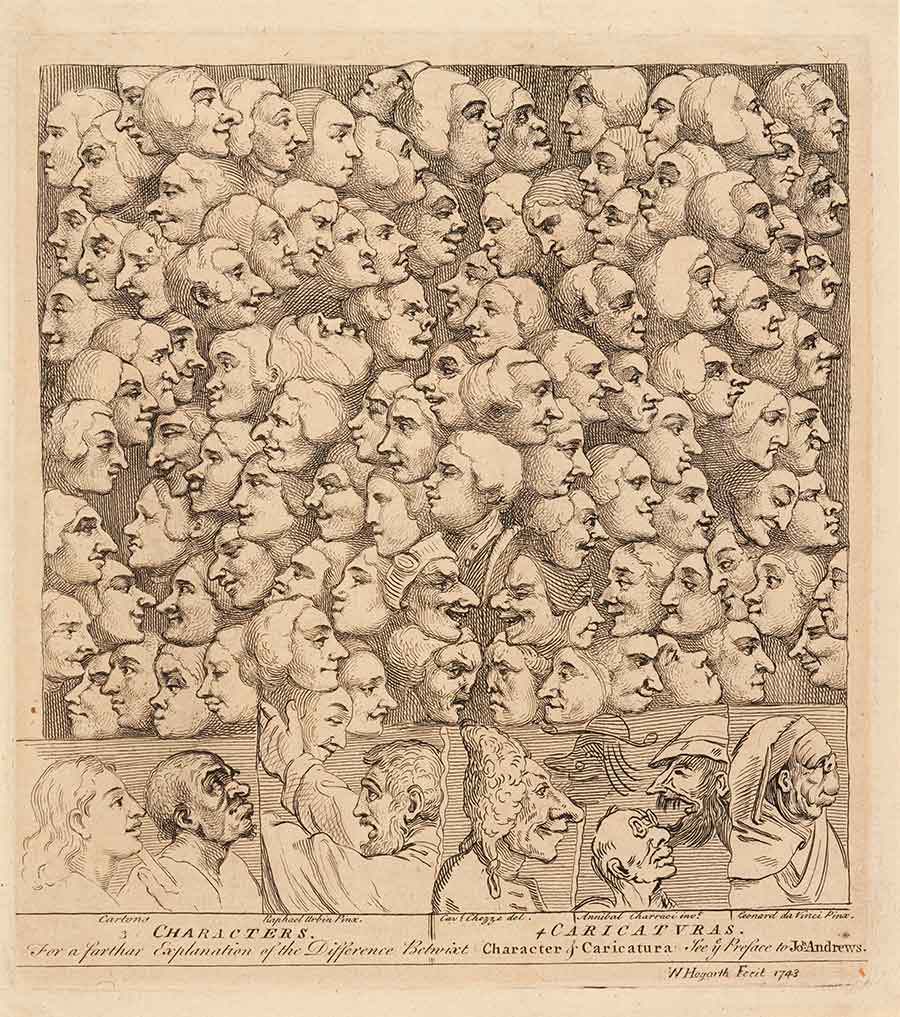

William Hogarth (1697–1764), Characters and Caricatures, 1743. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Stereotyping in early modern England and its colonies deserves scrutiny in our time because stereotypes were pervasive and affected the unfolding of profound events in the past as they still do today.

Recent events influenced by stereotyping include the two major political upheavals of 2016: the British referendum on membership in the European Union, and the American presidential election that vaulted a real estate tycoon with no prior experience in political office into the White House. In both cases, competing camps—including self-styled defenders of progressive values—stereotyped their opponents as unacceptable parties perpetrating great wrongs. A wide range of stereotypes were mobilized to orchestrate support and attack opponents—stereotypes of immigrants, African Americans, incompetent bureaucrats, metropolitan elites, and autocrats.

The political commentator Walter Lipmann (1899–1974), who coined the term “stereotype,” considered stereotyping an essentially modern phenomenon—modern in that its diffusion and impact supposedly rested on a range of contemporary mass media and large, literate audiences. This view becomes unsustainable as soon as we turn our attention to early modern history.

In November 1640, the English poet and politician Sir Benjamin Rudyerd (1572–1658) declared, “Under the name of a Puritan all our religion is branded,” highlighting the profound impact of the image of the Puritan that began to gain currency by the end of Queen Elizabeth I’s reign. Stereotypes were in fact ubiquitous in the early modern period. The image of the promiscuous Ranter (members of a religious sect that denied the authority of scripture and clergy) soon pervaded Interregnum England; during the late 1670s, stereotypes about non-conformism and popery played a vital role in the succession crisis surrounding the Catholic Duke of York.

James Gilray (1756–1815), London Corresponding Society alarm’d,—vide, guilty consciences, 1798. © The Trustees of the British Museum. 1851,0901.917.

Stereotyping was hardly limited to the sphere of domestic religious politics. There were stereotypical representations of the poor, the foreigner, the monopolist, the projector, the woman, and even of the "noisome air." We now know that the well-tried categories of popery and fanaticism provided a template for English diplomats to survey non-Christian religion and its relation to power in Ottoman Turkey. In other words, post-Reformation religious stereotypes served as heuristic tools for representing non-Christian "others" in the age of Enlightenment. Stereotyping could be found in almost every sphere of life in the early modern period—in politics, religion, the market, and even in the realm of learning.

This intriguing parallel between the early modern past and the present invites us to explore what we think is one of the fundamental questions about the nature of Enlightenment and progress. Proponents of liberal progress have often suggested that religious superstitions would soon go away, prejudices about poverty and illness would be gradually removed, and rational knowledge would triumph over vulgar errors. But if stereotyping persisted before the advent of the Enlightenment, if the Enlightened projects of learning and science themselves drew heavily on stereotypes as heuristic devices, and if stereotyping continues to persist to this day, what does progress stand for in relation to the human propensity to stereotyping? What lessons, if any, might historians (and curious citizens) draw from the past without falling into the trap of anachronism?

Historical research, if carried out comparatively with the help of appropriate conceptual tools, can help us confront this fundamental issue and question comforting prospects of removing stereotypes and underlying prejudices once and for all—a kind of unproven optimism all too often found in diluted narratives of modernity and progress.

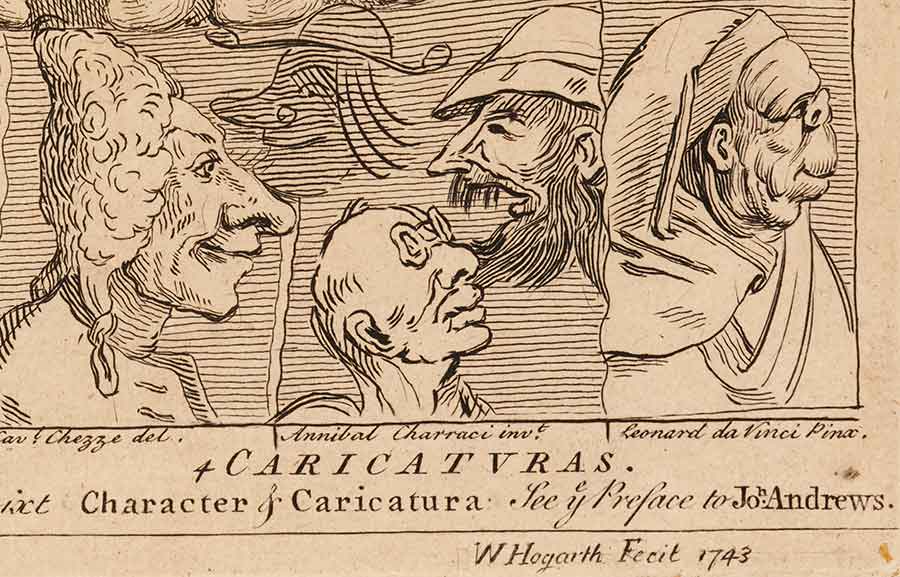

William Hogarth (1697–1764), Detail of Characters and Caricatures, 1743. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

At the conference we are convening, “Stereotypes and Stereotyping in the Early Modern World,” which will take place in The Huntington’s Rothenberg Hall from April 19–20, we hope to start developing comparative studies of stereotypes and stereotyping of important “others”—something that shaped religious, political, economic, and social life in early modern England and its colonies.

Note that the inclusion of the present participle—"stereotyping"—is deliberate. Through it, we wish to direct our critical attention not only at the contents of any stereotypical representations, but also at the ways in which these representations were invoked as prejudices or put to use in polemical exchanges. Only by studying stereotyping and its far-reaching consequences through concrete case studies can we begin to understand the power and perils of stereotyping, which continue to beset human interactions to this day.

In order to facilitate comparison among early modern case studies and between early modern past and the present, some appropriate conceptual tools will be discussed, drawn from sociology and social psychology. Early modern historians will benefit from the insights of social science researchers into present-day stereotypes, while at the same time offering useful insights into the dynamism of stereotyping based on early modern examples.

Peter Lake is University Distinguished Professor of History at Vanderbilt University.

Koji Yamamoto is associate professor of business history at the University of Tokyo.