The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

The Image of Empire

Posted on Wed., April 24, 2019 by

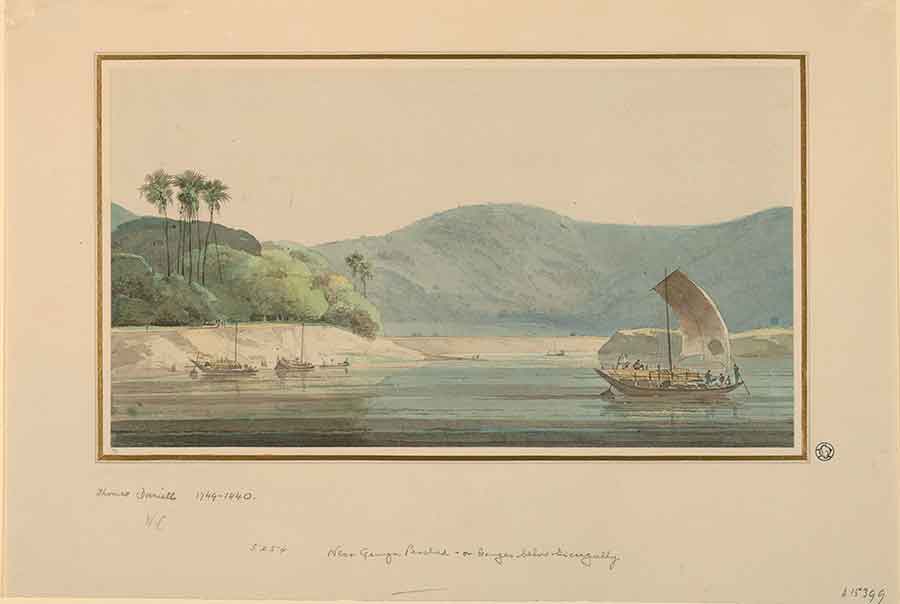

Thomas Daniell (British, 1749–1840), On the Ganges, ca. 1788, watercolor, Gilbert Davis Collection, 59.55.398. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

A placid river lazily flows past verdant hills, a high mountain retreat rests beneath towering pines, and delicate arches glow in the warmth of the setting sun. These evocative scenes each appear in a drawing made by a British artist attempting to describe the landscape of India. Such images conjure romantic dreams of exotic, faraway lands, but behind the dreamlike imagery, the story of British artists in India, and the places they depicted, is far more complicated. The 15 drawings on view through June 10th in the exhibition "Prospects of India: 18th- and 19th-Century British Drawings from The Huntington's Art Collections" in the Huntington Gallery Works on Paper Room were made during the period in which British interests there shifted from trade to Empire, though most barely hint at this history.

Thomas Daniell’s watercolor presents the river Ganges as a place of serenity, with calm, smooth waters and gentle, sloping banks. Like most British artists in late 18th-century India, Daniell had come to work for the British East India Company, the trading company first chartered in 1600 under Queen Elizabeth I to conduct trade around the Indian Ocean. By the time Thomas and his nephew William, who served as his assistant, arrived, however, the Company had expanded from its original trading mission and was now a military power seeking to gain territory. The landscapes the Daniells depicted were those that had come under Company control, either indirectly, through puppet governments, or via direct conquest.

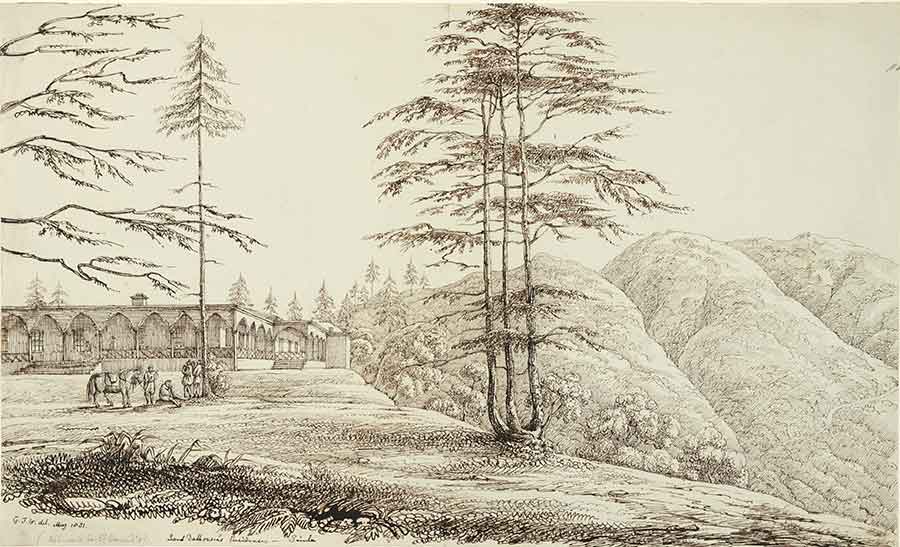

Col. George Francis White (British, 1808–1898), Lord Dalhousie’s Residence, Simla, 1831, pen and ink, 91.242. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

An image of lush, tree-covered mountains by George Francis White captures the forested beauty that drew the British to Simla (Shimla), on the southwestern ranges of the Himalayas. The British East India Company had taken command of the area in 1815 during the Anglo-Nepalese War. Accounts of its mild, British-like climate soon began to attract large numbers of officers and their wives, especially during the hot summers. Before long, this “Hill Station” became known as a place to socialize, and, in 1864, it was declared the summer capital of the British Raj (a term for British rule in India). An inscription on the drawing describes the building in the middle-ground as the house of Earl Dalhousie, the Commander-in-Chief of British forces.

William Edwards (British, active mid-19th century), View at Scinde, ca. 1843–46, watercolor, 78.5A. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

William Edwards shows a peaceful, idyllic landscape in a series of watercolors depicting the province of Scinde (Sindh, in present-day Pakistan), showing little trace of the region’s recent annexation by the British military. Edwards, in fact, had served as aide-de-camp to General Sir Charles Napier, whose ruthless and controversial campaign was famously lampooned in Punch. The magazine printed a spurious dispatch to the Governor-General of India in Napier’s name, announcing his victory with one word: “Peccavi.” Latin for “I have sinned,” it played on the homophone of the region’s name (sinned and Scinde are pronounced the same). This humorous acknowledgment of Napier's role in the violent invasion obscures the fact that differences in military technologies between British and local forces resulted in staggering statistics. In one battle alone, sources indicate some five or six thousand Baluch fighters were killed while British losses were only in the low hundreds.

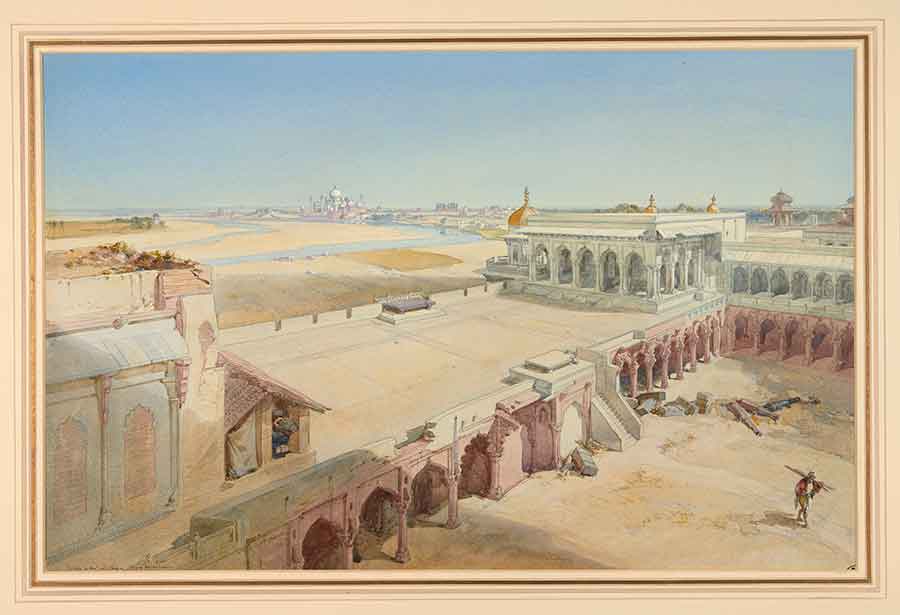

A high vantage point allows for an almost bird’s-eye view of an ancient fortress compound, where scattered cannons indicate a more recent conflict, in William Simpson’s finely rendered watercolor. Simpson was a correspondent and war artist for the Illustrated London News, making a name for himself with first-hand depictions of war zones. He was sent to India in the late 1850s to sketch scenes related to the recent Sepoy Mutiny (The Indian Rebellion of 1857, known in India and Pakistan as the First War of Independence). This scene shows the fort at Agra, the site of a battle during the Indian Rebellion, with the graceful domes of the Taj Mahal in the distance.

William Simpson (British, 1823–1899), Agra , 1864, watercolor over graphite, 59.55.1183. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

While celebrating the beauty of the Indian landscape, these images also allude, however indirectly, to the violence that lies at the heart of empire building, revealing the complexity of Britain’s engagement with South Asia during this period.

Melinda McCurdy is associate curator for British art at The Huntington.