The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Beatrix Farrand at The Huntington

Posted on Wed., Oct. 24, 2018 by

Portrait of landscape architect Beatrix Farrand (1872–1959), by Jeanne Ciravolo.

Documentary filmmaker and six-time Emmy Award-winner Karyl Evans will present a screening of her film "The Life and Gardens of Beatrix Farrand" at 7:30 p.m. on Monday, Nov. 12 in The Huntington's Rothenberg Hall. In anticipation of the screening, we have invited historian Ann Scheid to write about the work and life of Beatrix Farrand (1872–1959), including her time at The Huntington.

When Beatrix Farrand moved to California in 1927 with her husband Max, newly appointed as the first director of The Huntington, she was one of the most well-known and experienced landscape architects of her time. As the only woman among the 11 founding members of the American Society of Landscape Architects, she had an impressive list of commissions to her credit, including both private gardens and campus designs. Born into New York society (Edith Wharton was her maternal aunt), she counted Abby Aldrich Rockefeller and J. Pierpont Morgan among her clients. Her campus work included designs for Princeton, Yale, the University of Chicago, Vassar, Hamilton, and Oberlin colleges.

Beatrix Farrand, standing in front of the director's house at The Huntington. She and her husband, the historian Max Farrand (1869–1945), who was the first director of The Huntington, lived in the house during all but the first three years of his tenure, which lasted from 1927 to 1941. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Max Farrand, a well-known Yale professor specializing in constitutional history, had been selected by Huntington trustee and solar astronomer George Ellery Hale as the best candidate for the director position. The Hales and Farrands became close friends, and Beatrix designed her first California garden for Hale's solar observatory on Holladay Road, just north of the Huntington estate.

When the Farrands first arrived, they lived on South Orange Grove Avenue in Pasadena, but by 1930, they were living in the director's house off Orlando Road on The Huntington's grounds. A guest cottage located north of the original Library building had been moved to the site and remodeled into a residence. It is likely that Beatrix helped determine the siting and designed the landscape features around the house. Following the principle of her teacher and mentor, Charles Sprague Sargent of Harvard's Arnold Arboretum, to "make the plan fit the ground and not twist the ground to fit the plan," she sited the house on a knoll, reached by a curving drive from Orlando Road.

South facing exterior and “office” of the director’s house. Beatrix Farrand designed the paths and plantings around the office in the 1930s, using mostly hedges and flowers. Her original plans called for calla lilies, narcissus, iris, and freesias. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

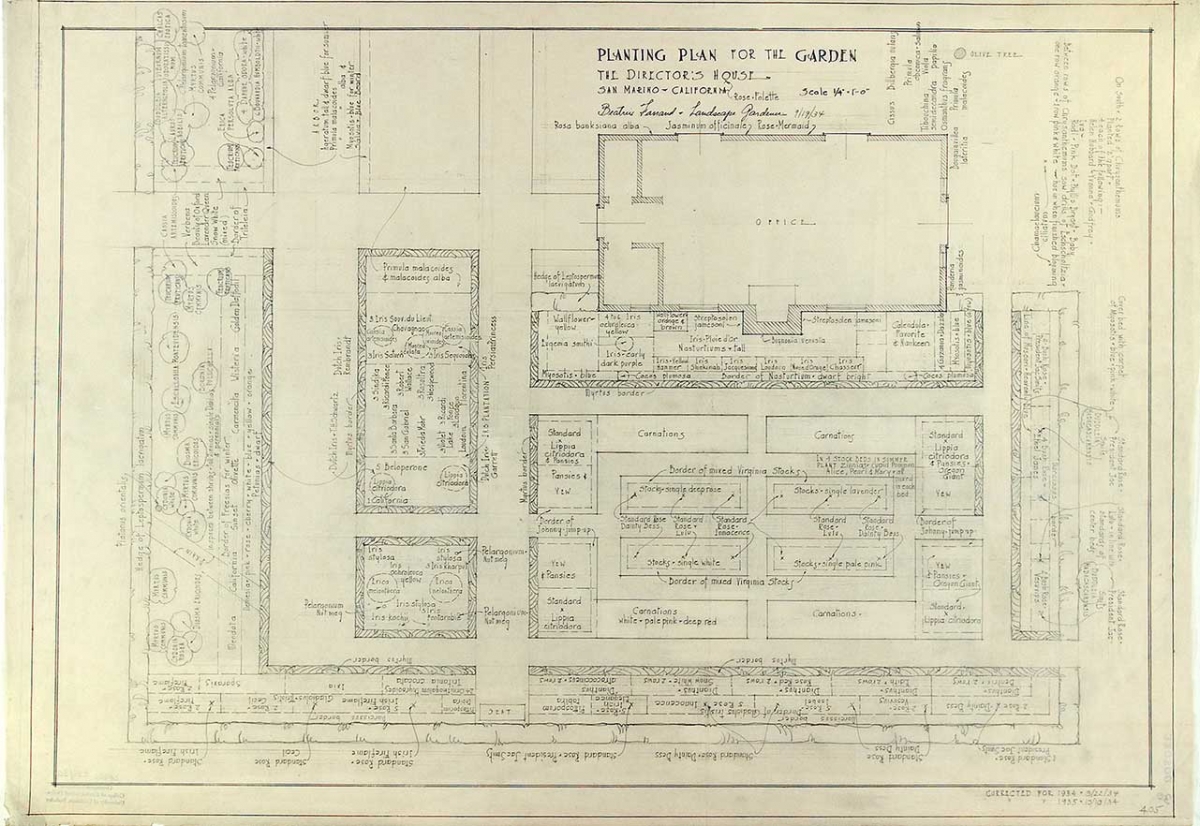

Respecting the symmetry of Myron Hunt's original design for the house, which had a centered entrance portico, she created a garden featuring a patio overlooking the lawn bordered by a garden wall. On axis with the patio, she mounted a fountain on the wall to serve as a focal point for the view from the house. At the west end of the garden, she asked Hunt to design a small office/studio linked to the main house by a pergola. Beyond the office was an intimate flower garden in raised beds. An allée of native oaks led from the east end of the property into The Huntington's grounds, a path that Max probably strolled on his way to the office. It is remarkable in the ephemeral world of landscape design that the basic elements of the garden still survive, although the flower garden has been replaced by a swimming pool.

Farrand continued working for her eastern clients through the 1930s, including Mildred and Robert Woods Bliss. Their estate, Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, D.C., is her most celebrated work and is now open to the public. Farrand also did some work for Caltech, including the design of Dabney Garden on the campus.

Beatrix Farrand's landscape design for the director's house at The Huntington, 1934. This revision of her original landscape design comprises carnations, pansies, roses, petunias, irises, and chrysanthemums, among others. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

However, her most significant work in Southern California is her campus redesign at Occidental College. Working closely again with Myron Hunt, she transformed the hilly campus accessed by a road into a series of gentle terraces, creating at one stroke a walkable horizontal campus with a quadrangle marked by mature oak trees that she personally selected in the wild and had moved into place. This reorientation of the campus incorporated the existing buildings and placed the new auditorium, Thorne Hall, on the west, balancing the existing library building on the east. She did additional work in Santa Barbara on the Bliss estate, Casa Dorinda in Montecito, and on the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden.

When the Farrands announced their retirement to their home, Reef Point, in Maine in 1941, Beatrix wrote to a friend: "Although this house [at The Huntington] has only been our official home and therefore not as closely rooted in our hearts as Reef Point, it is rather a tug at the heartstrings to leave its pleasant surroundings and the implication of all the friendly hours we have enjoyed it."

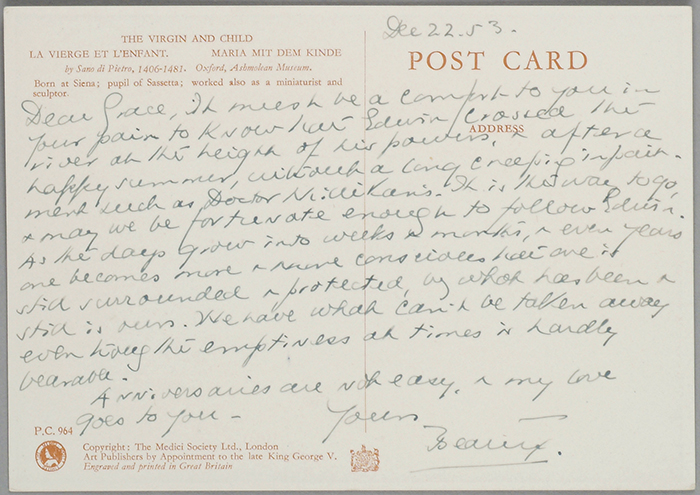

Beatrix Farrand sent condolences to her friend Grace Hubble, the wife of astronomer Edwin Hubble, after his death in 1953. Her note begins: “Dear Grace, it must be a comfort to you in your pain to know that Edwin crossed the river at the height of his powers . . .” Edwin Hubble Papers. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Besides the Hales, the Farrands counted as close friends astronomer Edwin Hubble and his wife, Grace. Another friend, feminist Clara Burdette, wrote of the Farrands: "Your presence has always given me an inward rejoicing that you were a living example to this community of two people who could each exercise a vital interest of his own and yet remain in unity—the high purpose of living."

Following the screening of "The Life and Gardens of Beatrix Farrand" at 7:30 p.m. on Monday, Nov. 12 in Rothenberg Hall, filmmaker Karyl Evans will discuss the restoration of Farrand's work at Yale University.

The program is presented as part of the California Garden & Landscape History Society Lecture Series. Free; no reservations required.