The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Yone Noguchi and Haiku in the United States

Posted on Wed., March 7, 2018 by

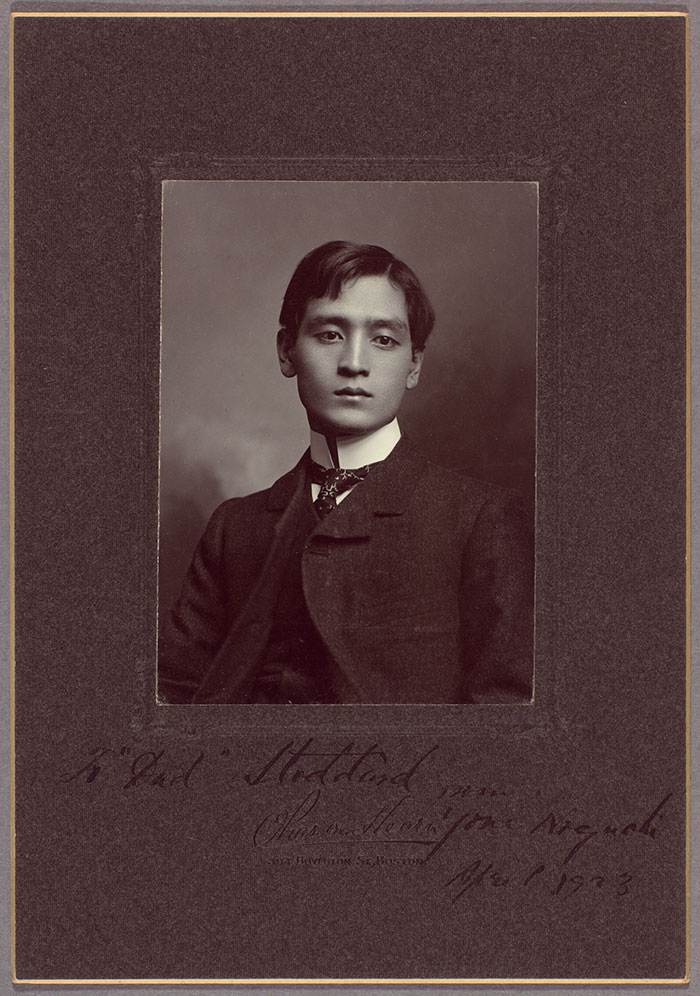

Photograph of Yone Noguchi, inscribed to Charles Warren Stoddard, April 1903. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Haiku is arguably the best-known form of poetry in the United States. Nearly every schoolchild in the U.S. has attempted to write a poem in three lines of seventeen syllables, arranged in the now familiar 5-7-5 syllable pattern. Traditionally, haiku focuses on natural themes and provides philosophical insight through the juxtaposition of two subjects. But how did this distinctly Japanese art form first come to the States?

The answer is a turn-of-the-20th-century Japanese man named Yonejirō Noguchi (1875–1947), better known in the U.S. as Yone Noguchi. Noguchi was the first Japanese writer to publish novels and poetry in the English language. His accomplishments have often been overshadowed by his son Isamu Noguchi (1904–1988), an internationally known sculptor and the product of a somewhat scandalous affair between Yone and American Léonie Gilmour (1873–1933).

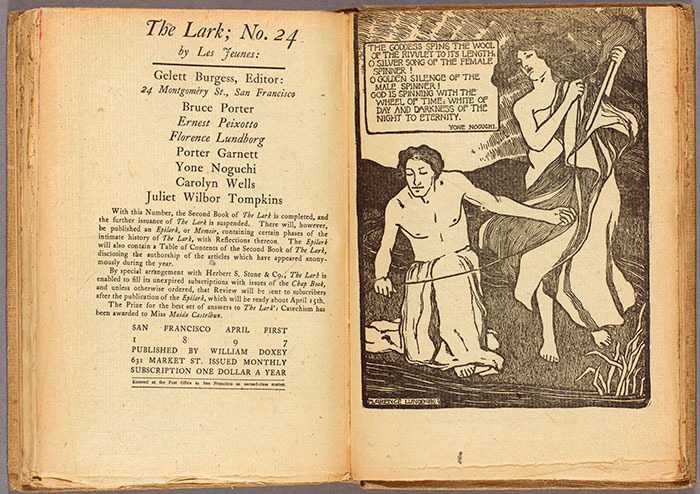

Noguchi’s poetry was first published in the United States in The Lark, a magazine edited by Gelett Burgess in San Francisco. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Born in Tsushima, Japan, Noguchi was fascinated with English at a young age. Bored with his prep school studies, he travelled to San Francisco in 1893 to immerse himself in the language. There he befriended the poet Joaquin Miller (1837–1913), who introduced him to other literati, including Charles Warren Stoddard (1843–1909) and Gelett Burgess (1866–1951). Burgess published Noguchi’s poetry in his magazine The Lark.

The first volume of Noguchi’s poetry, Seen and Unseen, or, Monologues of a Homeless Snail, appeared in 1897. Filled with his Whitmanesque free verse and imperfect English, it also included translations of two haiku by the 17th-century Japanese poet Matsuo Bashō (1644–1694) in the introduction. To Noguchi’s surprise, the volume was a success, and he began to earn a reputation as a man at the convergence of East and West.

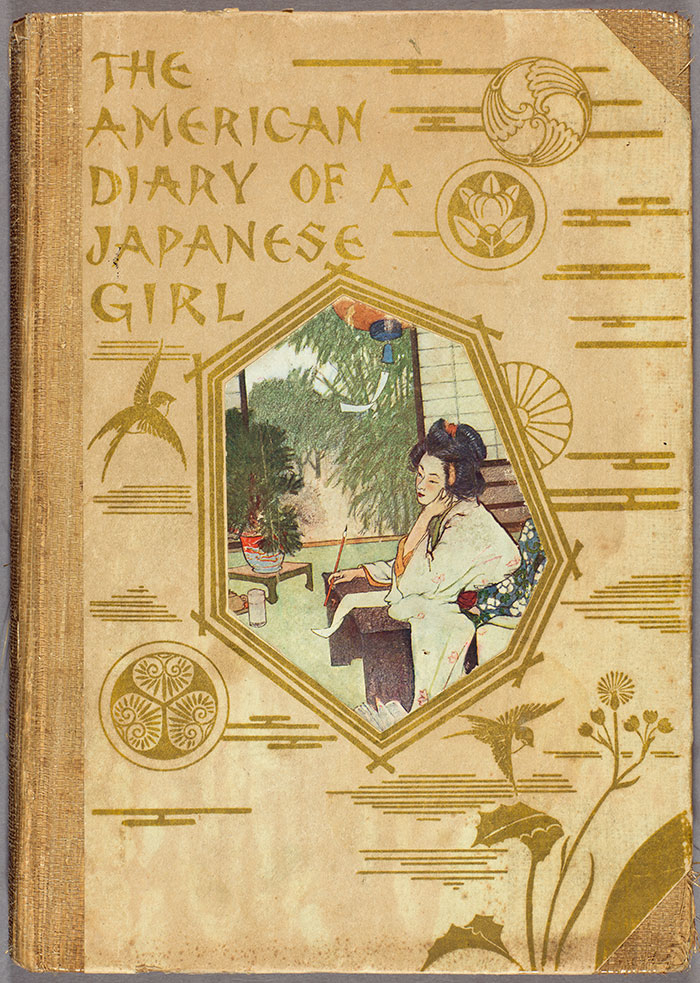

Noguchi’s The American Diary of a Japanese Girl, published in 1902, was the first novel published in the United States by a Japanese writer. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

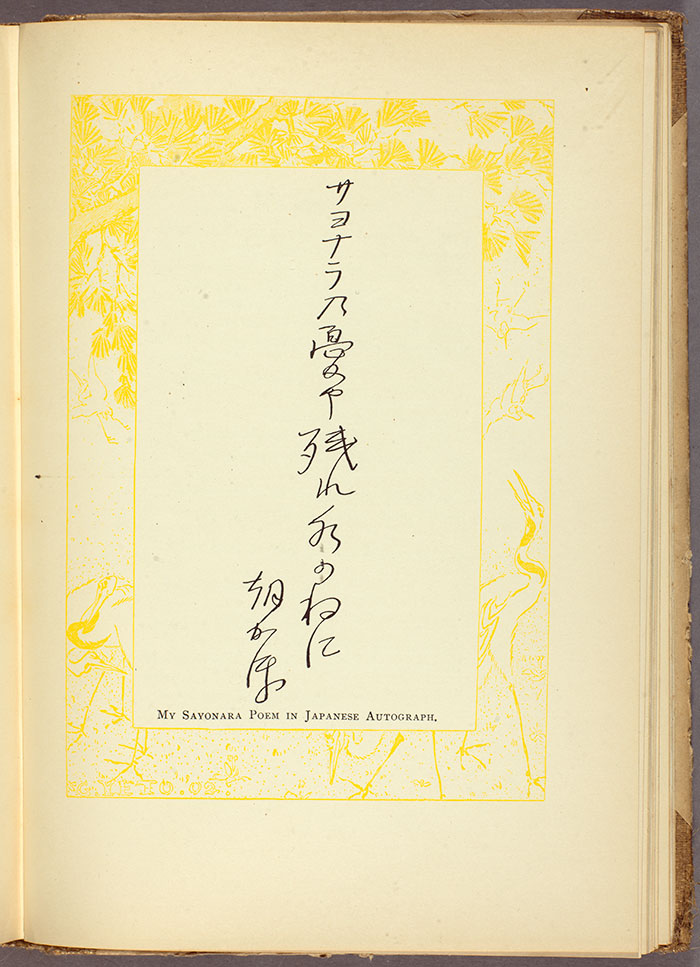

Noguchi moved to New York City, and in 1902, his The American Diary of a Japanese Girl became the first novel published in the United States by a Japanese writer. Riffing on the popularity of Pierre Loti’s 1887 novel Madame Chrysanthème and John Luther Long’s 1898 short story “Madame Butterfly,” Noguchi also fictionalized some of his own experiences in California for the tale. Initially attributed to the pseudonymous “Miss Morning Glory,” the purported autobiography follows an 18-year-old Japanese girl on her transcontinental visit to the United States with her uncle. As she prepares to leave San Francisco, she writes a farewell haiku:

Sayonara no

Ureiya nokore

Mizu no neni!

Remain, oh remain,

My grief of sayonara,

There in water sound!

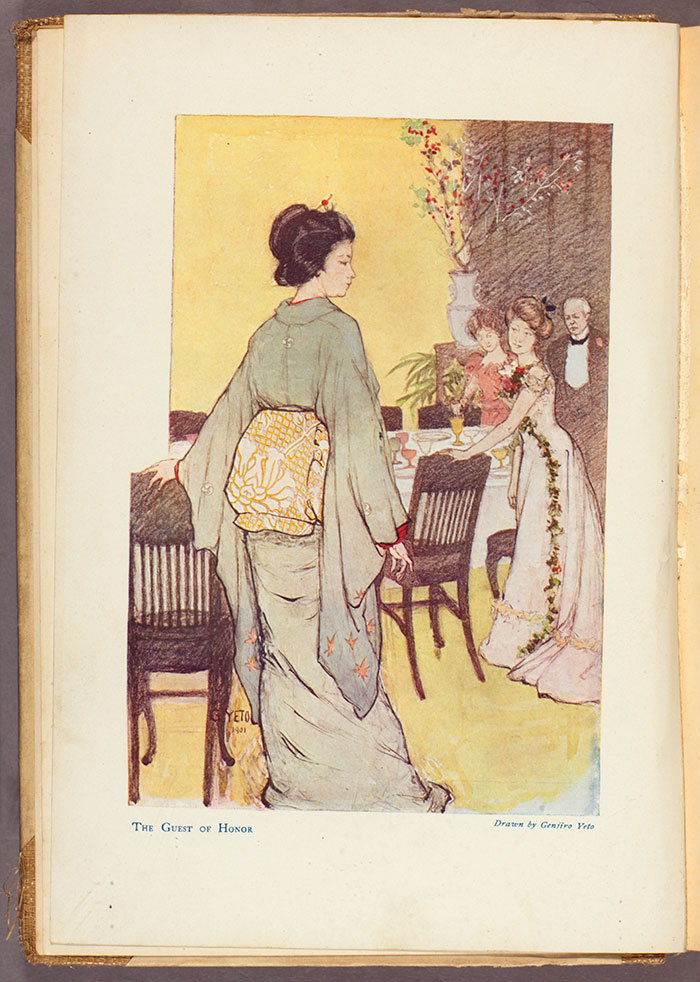

Noguchi’s novel The American Diary of a Japanese Girl was initially attributed to the pseudonymous Miss Morning Glory, an 18-year-old Japanese girl on a transcontinental tour of the United States. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In February 1904, Reader magazine published an essay by Noguchi: “A Proposal to American Poets.” In it, Noguchi encourages American poets to try writing Japanese haiku, or hokku, as he preferred to call them, using an older term. He compares hokku to “a tiny star . . . carrying the whole sky at its back” and “a slightly open door, where you may steal into the realm of poesy.” Simplicity and the power of suggestion, Noguchi argues, offer a superior poetic form. In contrast, he notes that “I always compare an English poem with a mansion with windows widely open, even the pictures of its drawing-room visible from the outside. I dare say it does not tempt me much to see the within.”

Noguchi goes on with examples of his translations of poems by Bashō, as well as a few hokku of his own creation. He admonishes: “Pray, you try Japanese Hokku, my American poets! You say far too much, I should say.”

Miss Morning Glory’s farewell haiku, the first original haiku published in an English novel. Translated, the poem reads: “Remain, oh remain, / My grief of sayonara, / There in water sound!” The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In August 1904, Noguchi returned to Japan and accepted a position as a professor of English at Keio University. He married a Japanese woman and continued publishing in English. He received critical success in Europe through the 1910s, where his ideas about haiku sparked the interest of the U.S. poet Ezra Pound (1885–1972) and the Imagists. American poets slowly explored the form, which gained serious traction during the Japanophilic 1960s. Today, English-language haiku is a staple of American poetry.

The quality of Noguchi’s poetry and his translations have been debated by scholars over the years, as has the extent of his influence on the popularity of haiku. But his early attempts to bring a taste of Japan to America are undeniable.

Natalie Russell is assistant curator of literary collections at The Huntington.