The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

From the Word to the World

Posted on Thu., Oct. 26, 2017 by

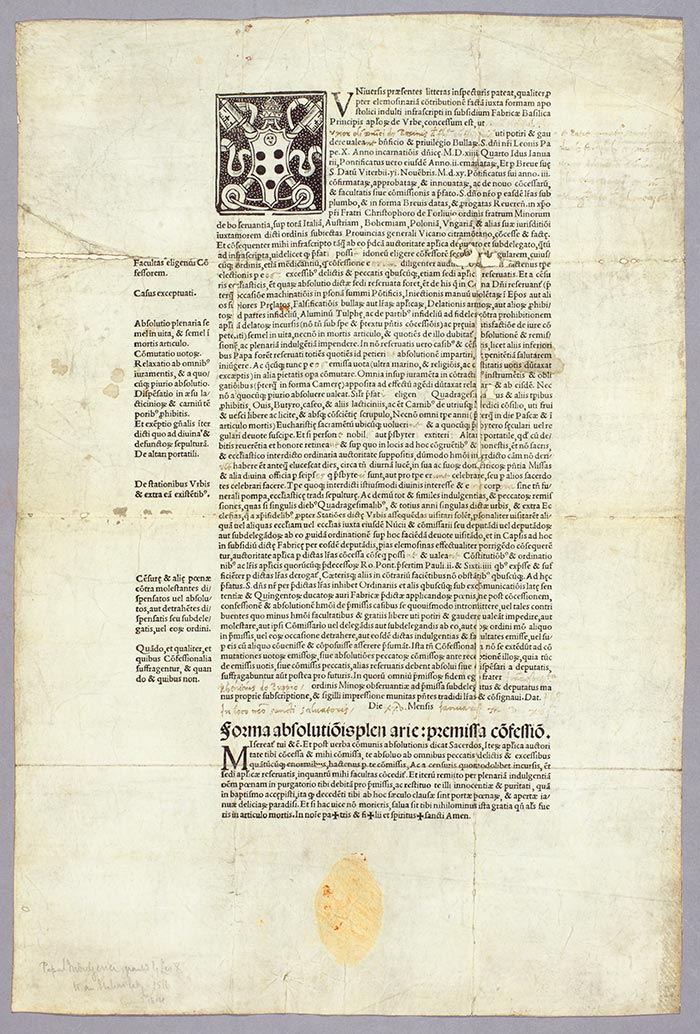

Papal indulgence issued by Pope Leo X, Florence, 1515. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

To mark the 500th anniversary of the Reformation, The Huntington is mounting an exhibition that explores the power of the written word as a mechanism for radical change. “The Reformation: From the Word to the World” is on view in the West Hall of the Library from Oct. 28, 2017, to Feb. 26, 2018.

On Oct. 31, 1517, German priest Martin Luther (1483–1546) is said to have posted a document on the door of a church in Wittenberg to contest practices of the Catholic Church. With these “95 Theses,” as his disputes are known, Luther was looking to stimulate thoughtful debate that would clear away corruption and pomp, and thus reform the Church. What followed was a flurry of arguments and ideas put forth by scholars, clerics, and statesmen that fueled a movement called the Reformation.

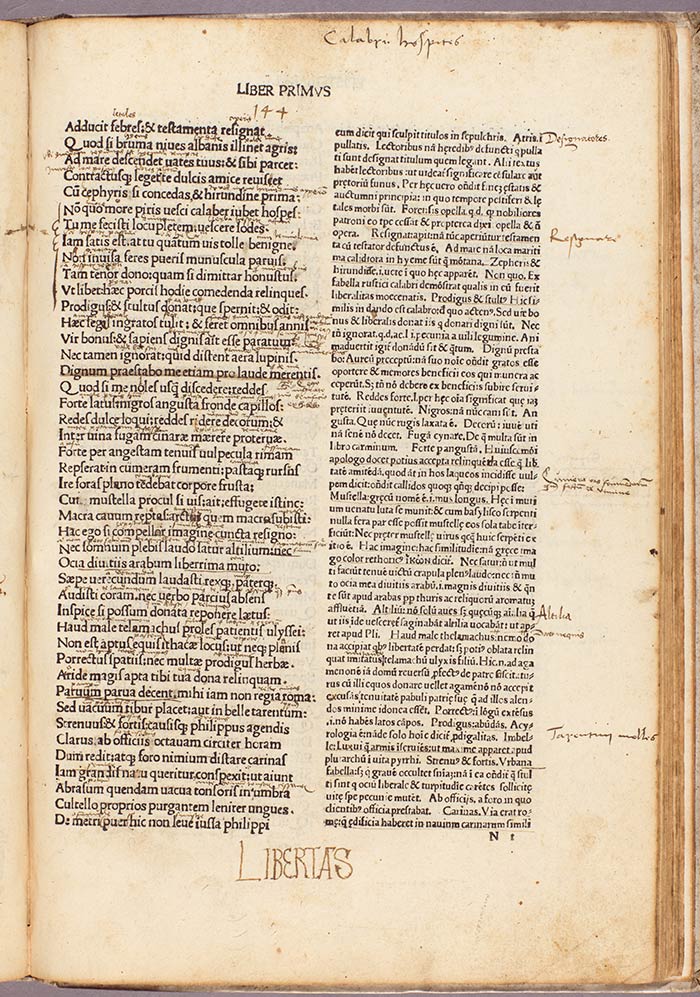

Horace, Works, Venice, 1483, annotations by Martin Luther (1483–1546). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

“This was an act of protest, yet it was also an act of faith,” says Vanessa Wilkie, the William A. Moffett Curator of Medieval Manuscripts and British History at The Huntington, and the curator of the exhibition. In selecting the 50 items for the exhibition, Wilkie delved into some of the earliest holdings in The Huntington’s vast collection. A papal indulgence issued by Pope Leo X in 1515 emerged, as did an edition of Horace’s Works published in 1483 and heavily annotated in Luther’s own hand.

Papal indulgences, targeted as an abuse by Luther and other clerics, promised the buyer remission of the punishment of sin and raised money for the church. The example on display—a pre-printed form completed for a specific purchaser—lists the blessings to be received by a mother and her sons and notes that the income would go toward building St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

The annotated Horace, an incunable (a book printed before 1501), indicates not only what Luther read, but also what he gleaned from his reading and how he shaped his arguments. A graphic blow-up of a heavily annotated page from this book greets visitors as they enter the exhibition.

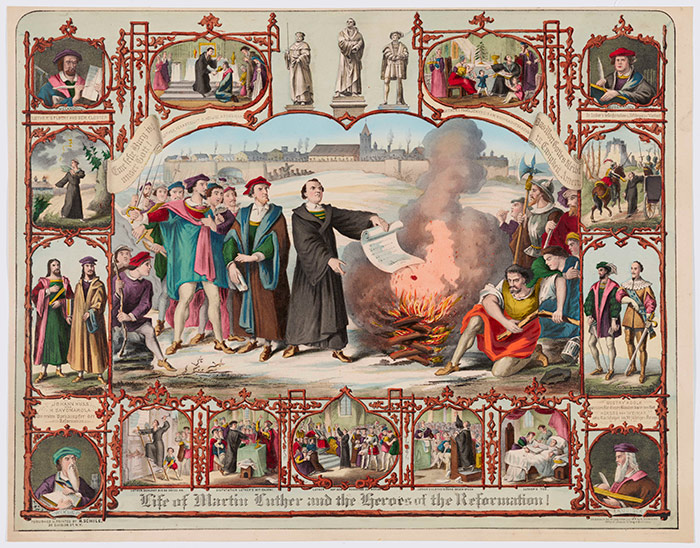

H. Breul and H. Brückner, Life of Martin Luther and Heroes of the Reformation, 1874, hand-colored lithograph, H. Schile; New York. The Jay T. Last Collection of Graphic Arts and Social History. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Also on display is a large lithograph from 1864, Life of Martin Luther and Heroes of the Reformation, which valorizes Luther, depicted in the dominant center panel, brandishing his theses. But the lithograph also shows, in miniature portraits in the lower corners, the 14th-century dissidents John Wycliffe (1320–1384) and Jan Hus (1369–1415). “Many see the Reformation as Luther finishing their fight,” says Wilkie. “In his own time, Luther was tied into larger debates taking place across Europe and was not the only cleric to publish justifications for his beliefs.”

The spark of the Reformation spread through reading, writing, and printing practices of the period. Texts were widely disseminated to articulate beliefs, ignite reforms, and attack adversaries. European governments and religious councils, anxious to regain control, banned books to minimize the spread of works they deemed dangerous. Words, texts, images, and prints blurred the divisions between thinkers, heroes, and martyrs. “The Reformation did not just play out in pulpits and on battlefields—it lived on the page,” says Wilkie.

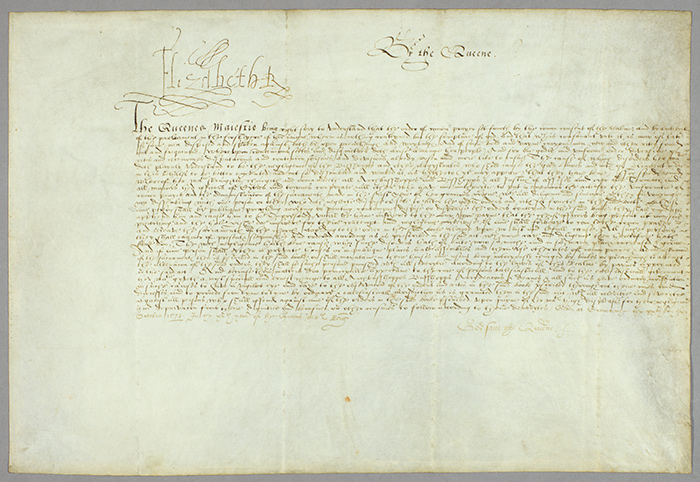

Proclamation signed by Queen Elizabeth I in 1573, requiring the use of the Book of Common Prayer. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Other items on display include early 16th-century prints by Albrecht Dürer, one of the most influential artists of the Reformation, and the 1573 original manuscript proclamation, signed by Queen Elizabeth I, requiring the use of the Book of Common Prayer. Long after the arrival of the printing press, a handwritten manuscript, by law, served as the original from which proclamations should be printed and distributed. Queen Elizabeth I’s Royal Proclamation against despisers of the Books of Common Prayer of 1573, bearing the monarch’s bold and elegant signature, is a rare surviving example.

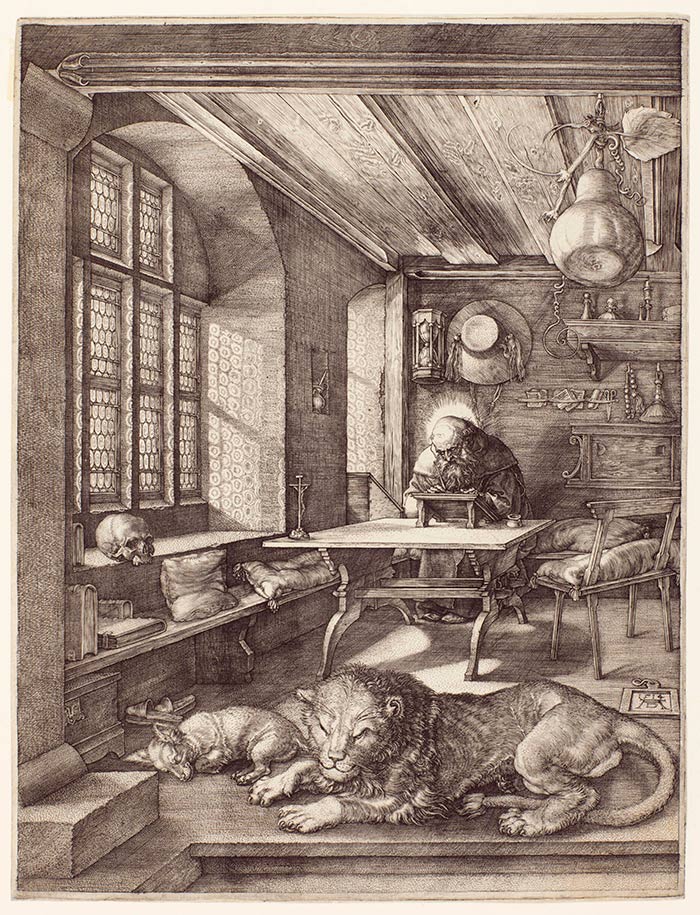

Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) was one of the most influential artists of the Reformation. Pictured here, his engraving of St. Jerome in his Study, 1514. Edward W. and Julia B. Bodman Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

A 1514 engraving by Albrecht Dürer, St. Jerome in His Study, stands in contrast to a rendering of this perennially well-loved subject from a lavishly decorated 15th-century Flemish Book of Hours. Dürer reflects the shifting perspectives of his age (he was among the first European artists to inject his own ideas into his work), creating a meticulously detailed portrait of an individual in contemplation. In Dürer’s The Knight, Devil, and Death, the steadfast knight, fired by his moral courage, rides onward despite his lethal pursuers.

A hand-drawn image in a jocular vein, William Bowyer’s “The Voracious Abbot,” from the manuscript collection Heroica Eulogia (1567), skewers the corruption of some clergy. The monk caresses a suckling pig that he’s about to devour.

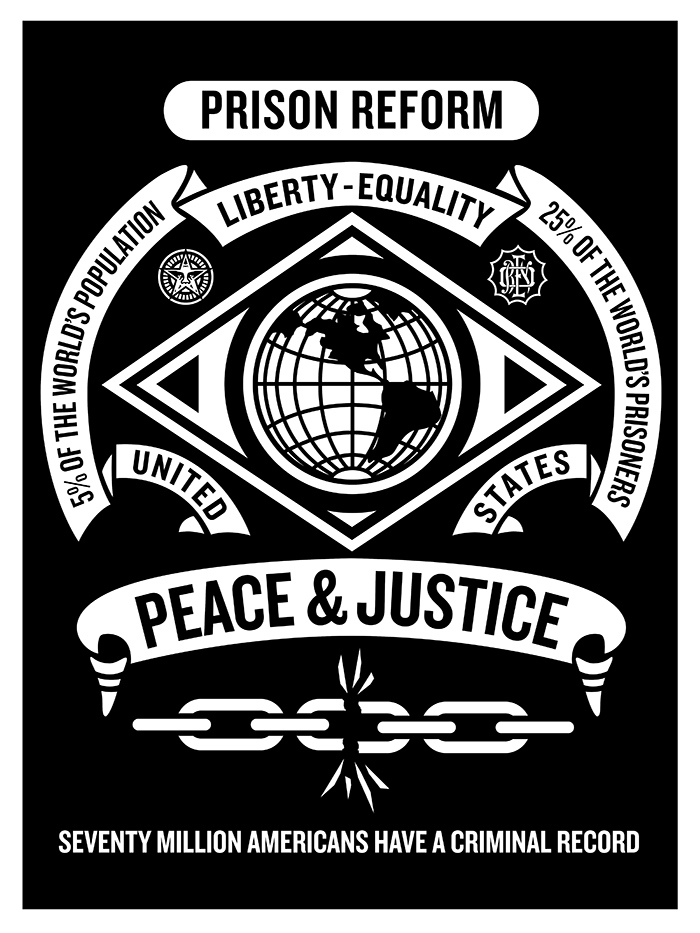

A public statement from our own age, Shepard Fairey’s Prison Reform poster (2015), applies an older graphic style to a current issue, reminding the viewer that it has a lengthy history.

Shepard Fairey, Prison Reform, 2015. Illustration courtesy of Shepard Fairey/Obeygiant.com.

“The voices of the Reformation had lots of formats to express their views,” says Wilkie. “We have even more today: podcasts, social media, fashion, protest posters.” Visitors can mirror Luther and his peers by writing or drawing on cards that can be affixed to the exhibition’s Gothic door or shared on social media using the hashtag #WordtoWorld.

The exhibition poses questions that can stimulate conversations about how we encounter these themes in our own lives. Wilkie asks, “What is so important to you that you’d nail a statement about it in a public place for all to see? It’s an opportunity to think deeply about how we reinterpret and transform words and images from the past to engage in debates of our own time.”

What do you want to tell the world? And how do you want to share your message?

“The Reformation: From the Word to the World” is on view in the West Hall of the Library from Oct. 28, 2017 through Feb. 26, 2018. The exhibition is made possible by the generous support of the Robert F. Erburu Exhibition Endowment.

The related conference, “Globalizing the Protestant Reformations,” which takes place Dec. 8–9, 2017, in Rothenberg Hall, examines how Protestantisms spread across the globe. You can watch a video of Vanessa Wilkie talking about the significance of one of the items in the exhibition—a private, handwritten version of the 1559 Book of Common Prayer—on YouTube.

Linda Chiavaroli is a volunteer in the office of communications and marketing.