The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

West of Walden

Posted on Mon., April 3, 2017 by

Shortly after the publication of Walden in 1854, Samuel Worcester Rowse, an artist famous for his fashionably sentimental portraits, sketched this portrait of Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862). Prudence Ward, who sent this reproduction to Anne J. Ward, was a permanent boarder in the Thoreau household. Correspondence of Prudence Ward and Anne J. Ward, 1839–1906. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

“Walden. Yesterday I came here to live.” That entry from the journal of Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862), and the intellectual journey it began, would by themselves be enough to place him in the American pantheon of writers and thinkers. His attempt to “live deliberately” in the woods at the edge of his hometown of Concord, Mass., has been a touchstone for individualists and seekers since the publication of his Walden in 1854.

Thoreau famously concludes Walden with the line “The sun is but a morning star”—declaring that this, his morning book, celebrates dawn and first light. As the book’s motto affirms, he’ll brag “as lustily as chanticleer in the morning, standing on his roost, if only to wake my neighbors up.” And wake us up he did: to the dawn of democracy and civil rights, to the first stirrings of American environmentalism and the earliest call to protect the nation’s wild places. Yet elsewhere in his writings, Thoreau looks westward to the close of day.

Thoreau’s cairn at Walden Pond, looking west, ca. 1895. Bronson Alcott laid the second stone in this cairn, after watching his friend Mary Newbury Adams lay the first stone during a visit to Walden in 1872. The cairn, which stands near the site of Thoreau’s house, continues to grow daily. Correspondence of Prudence Ward and Anne J. Ward, 1839–1906. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

For example, he ends his essay “Walking”—that westward journey of his imagination—by remembering the “great awakening light” of sunset, which gleamed on the westward side of every tree and all the rising ground “like the boundary of Elysium, and the sun on our backs seemed like a gentle herdsman, driving us home at evening.” To Thoreau, west meant the future, the unknown, the possible, the earth still unexhausted and richer; as he summed up, “The West of which I speak is but another name for the Wild; and what I have been preparing to say is, that in Wildness is the preservation of the world.”

The conference “West of Walden: Thoreau in the 21st Century,” taking place on April 7 and 8 in Rothenberg Hall, commemorates the bicentennial year of Thoreau’s birth from the sundown side, reading his life and work from the far west of his imagination. California is the perfect setting in which to consider Thoreau today, standing as it does on the western verge of America. Thoreau always dreamed of travelling west and read with envy of the Pacific Coast. Though he made it only as far as the Mississippi River and the Minnesota prairie, seven draft manuscripts of Walden made it all the way to California: they are housed here, at The Huntington.

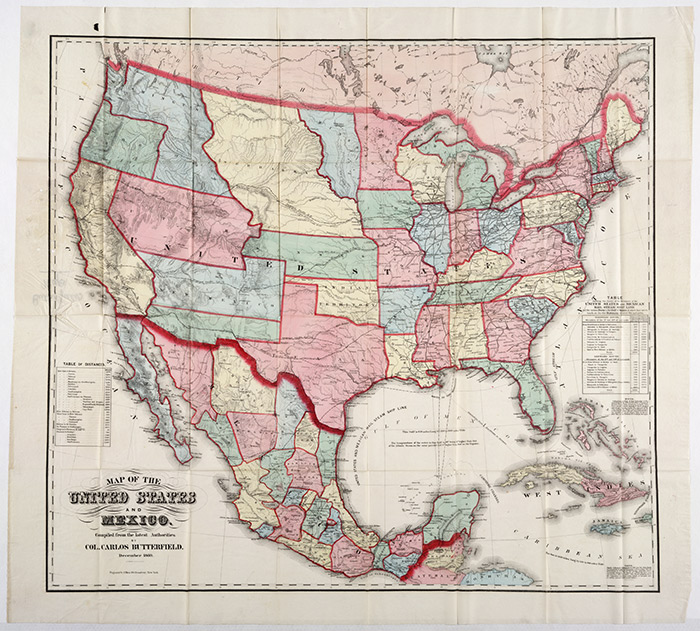

This popular map shows that the United States had already grown to its present continental borders by 1860, though many of the western states had yet to be created. Map of the United States and Mexico, compiled from the latest authorities, by Col. Carlos Butterfield. Publisher: Julies Bien (1826–1909), New York, December 1860. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Conceptually, too, Thoreau’s later work traveled from dawn and spring daylight to day’s end and the darker lights of autumn. As he looked to the future of his nation, he saw great promise ahead—but he also saw great peril, fearing for the coming of the “evil days” when wild lands would be fenced and built over, and nature’s goodness would come to us not freely, but priced and prepackaged for the market. This gathering of eminent Thoreau scholars will consider how to read Thoreau from our own day, a time when we sense a sunset coming and anticipate the dawn of a new day.

In four sessions over two days, we will look at the widening circles of Thoreau’s career as a poet-naturalist, and of his friends, correspondence, and reform efforts; we’ll reflect on the westward turn of his environmental imagination, and the global contact zones where he encountered other cultures and literatures. Thoreau, in his life and practice, joined humans and nature, speaking for both environmental protection and social justice. During our time together, we will ask: How does Thoreau help us to see our past? What are his gifts to us? How can his gifts help us envision our future—and anticipate our own morning star?

The west of the imagination: “Every sunset which I witness inspires me with the desire to go to a west as distant and as fair as that into which the Sun goes down,” wrote Thoreau. Sunset over California, as envisioned in 1868 by Albert Bierstadt, America’s premier painter of the West. A lithograph reproduction of Sunset (California scenery) by Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902), from Prang’s American chromos, L. Prang & Co., Boston (Mass.), 1868, Jay T. Last Collection of Graphic Arts and Social History. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

You can read more about the conference program and registration on The Huntington’s website.

In conjunction with the conference, The Huntington will display, in the foyer of the Library’s Main Exhibition Hall, one of the seven drafts of Walden housed in the Library, along with the autograph manuscript of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s funeral oration for Thoreau. A page from Walden is also on view in the Library’s permanent main hall exhibition, “Remarkable Works, Remarkable Times.”

Related content on Verso:

Society and Solitude in Concord (June 14, 2016)

Laura Dassow Walls is the Willliam P. and Hazel B. White Professor of English at the University of Notre Dame and the author of the forthcoming biography Henry David Thoreau: A Life, which will be published by the University of Chicago Press in July 2017.