The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Thomas Browne and His World

Posted on Thu., Jan. 21, 2016 by

In his scientific writing, Thomas Browne reveled in the mysteries of nature—how a caterpillar turns into a butterfly, for instance, or why stones and flowers assume certain regular shapes. He also debunked myths about fantastical creatures, such as the phoenix, the gryphon, and the amphisbaena (a mythical serpent with a head at each end). Detail from Christian Egenolff’s Herbarum, arborum, fructicum, frumentorum ac leguminum, 1552. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The idiosyncratic physician, essayist, and naturalist Thomas Browne (1605–82) produced a diverse body of writings that reveal a cornucopian range of interests at once scientific and religious: burial practices and mortality (Urn-Burial), the geometrical patterning of nature (Garden of Cyrus), and the perpetuation of errors and falsehoods across various disciplines (Pseudodoxia Epidemica, or Vulgar Errors). Browne’s interests were not singular to him but emerged out of conversations with some of the most influential natural philosophers of his era—such as Bacon, Descartes, Boyle, and Hooke—as well as conversations with his many correspondents and figures from the medieval and classical past.

To retrace the paths of these conversations, I am convening a dozen scholars at The Huntington on Jan. 22 and 23 for a conference titled “Truth and Error in Early Modern Science: Thomas Browne and his World.” The conference will bring together a half-dozen scholars working directly on Browne with six more whose work addresses broader developments in the scientific and intellectual culture of 17th-century England and Europe.

Browne strove, in his writing, to reveal nature’s mysteries, such as the hidden crevices of the subterranean world. Detail from Athanasius Kircher’s Mundus subterraneus, 1678. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Six of our participants, including myself, are currently working on a new scholarly edition of Browne’s Complete Works for Oxford University Press. Given the encyclopedic breadth of his writings, editing Browne is a remarkable conversation-starter, one that has obliged me to reach out to fellow scholars for expertise on subjects ranging from the circulatory system of trees and technical treatises on gunpowder to the making of porcelain in 17th-century China and early modern attempts to locate the source of the Nile. “Truth and Error” will allow select members of the Browne editorial team to have a sustained conversation with fellow scholars whose assistance we need most: intellectual and literary historians of 17th-century England, as well as early modern historians of science whose research focuses on some of the scientific topics of greatest interest to Browne—mineralogy, technology, astronomy, and mathematics.

Who was Thomas Browne? A physician, trusted for his expertise and bedside manner, and one who expressed contempt for the expensive and ineffective medicines prescribed by the medical charlatans of his day. A lay theologian who confessed his youthful vulnerability to various heresies and prided himself on his willingness to pray alongside Catholics and “converse and live” among the Jews of 17th-century Italy. A collector of natural oddities, curious about everything from the volcanoes of Iceland to the sex life of plants, whose domestic menagerie included an ostrich.

Browne was also a master prose stylist whose syntactic acrobatics and arcane, heterogeneous diction has been admired and imitated by subsequent writers—including Samuel Johnson, Coleridge, and Borges. He has always been a literary and intellectual hero for eccentrics and outliers, a “cracked Archangel,” as Herman Melville once called him.

But whereas Virginia Woolf, writing in 1923, observed that “Few people love the writings of Sir Thomas Browne,” the writer is currently enjoying a flood of attention from a new generation of scholars fascinated with his eclecticism, congeniality, tolerance, and curiosity about the natural world.

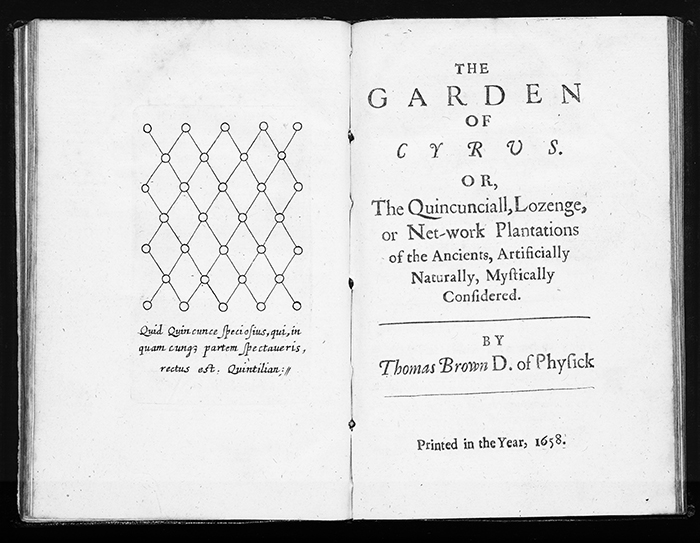

A committed experimentalist whose methods as a physician and naturalist anticipated and eventually complemented the labors of the Royal Society, Browne nonetheless diverged in certain respects from the prevailing spirit of scientific observation and experiment by exploring not only the natural, but also the mystical signification of what his Garden of Cyrus termed the “Quincunctiall” patterns he discerned throughout the plant and animal world. (An example of a quincunx is the pattern of dots on the five-side of a die.) Nature, to Browne, was both an open book and a hidden, recondite alphabet of symbols, a “common Hieroglyphick,” as he calls it in Religio Medici. Pages, rendered here in black and white, from Thomas Browne’s Hydriotaphia, urne-buriall, or a discourse of the sepulchrall urnes lately found in Norfolk: Together with The garden of Cyrus, or The quincunciall lozenge, or net-work plantations of the ancients, artificially, naturally, mystically considered, 1658. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Jessica L. Wolfe is professor of English and Comparative Literature and director of the program in Comparative Literature at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. She is the author of Homer and the Question of Strife from Erasmus to Hobbes (2015), published by University of Toronto Press, and Humanism, Machinery, and Renaissance Literature (2004), available from Cambridge University Press.