The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Solar Eclipse Observations

Posted on Thu., Aug. 17, 2017 by

On August 21, 2017, millions of people across North America will experience a total solar eclipse as the moon passes between the sun and Earth, completely covering the face of the sun for as long as several minutes. In anticipation of this rare event, we invited the distinguished astronomer Jay M. Pasachoff—Field Memorial Professor of Astronomy at Williams College and a Reader at The Huntington—to explore the scientific phenomenon of the solar eclipse by looking at items from The Huntington’s collections.

Étienne Trouvelot’s chromolithograph of the 1878 total solar eclipse that he observed in Creston, Wyoming Territory. The August 21, 2017, total solar eclipse will pass through Wyoming again. Jay T. Last Collection of Graphic Arts and Social History. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The umbra of the total solar eclipse on August 21 will sweep across the continental United States from Oregon to South Carolina, passing through parts of 14 states in a band roughly 65 miles wide. I will be in Oregon to view the event, the 34th total solar eclipse and 66th solar eclipse of my career. Experiencing the eerie darkness of a solar eclipse can be thrilling. They happen frequently—every 18 months somewhere in the world, though not usually so conveniently located—and they are often awe inspiring.

Scientists study the sun’s corona—the halo of hot gas around the sun held in place by its magnetic field—during a solar eclipse. Observers didn’t always comment on the corona. Hundreds of years ago, scientists focused primarily on the timing of an eclipse, noting its beginning, end, and duration. Perhaps the first scientist to comment on a corona during an eclipse was the German astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571–1630). In his 1604 book Optics, which can be found in The Huntington’s collection, he expressed the (erroneous) belief that the corona was probably the atmosphere of the moon.

The title page of Ad Vitellionem paralipomena quibus astronomiae pars optica traditvr, 1604, by the German astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571–1630). In this book, better known as Kepler’s Optics, Kepler commented on the sun’s corona during a solar eclipse. He erroneously believed it to be the atmosphere of the moon. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In 1715, Edmund Halley (1656–1742), of comet fame, published a broadside showing the shadow of the moon crossing England, and in the text below asked people to send in observations—something that today we might call “citizen science.” He received enough data to refine his results by about 40 miles, and then he published another broadside with a corrected 1715 path and a prediction for the 1724 eclipse, whose path of totality proceeded from England to the European continent.

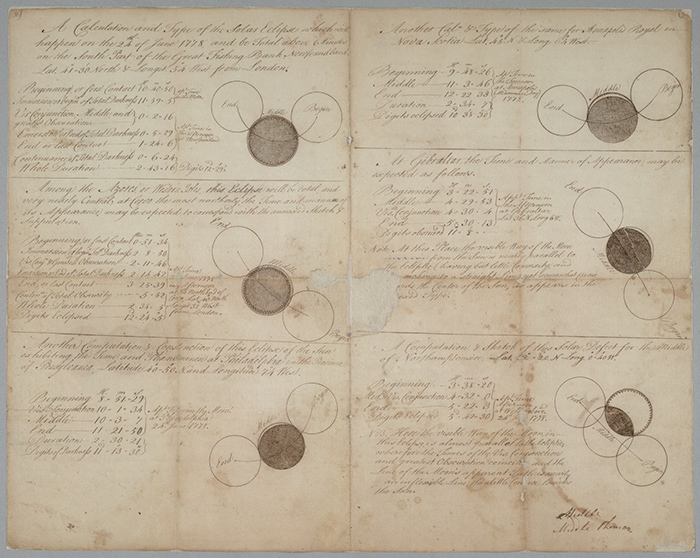

Later in the 18th century, Thomas Cowper, working in the same scientific tradition as Halley, produced illustrations and detailed observations of a solar eclipse in a unique manuscript now housed at The Huntington. Cowper’s drawings show a solar eclipse as observed in England, Nova Scotia, Pennsylvania, and Newfoundland on June 24, 1778. Cowper provided details of the appearance and timings of the eclipse based on information gathered from a network of solar observers located around the world.

Thomas Cowper’s calculations and drawings of a solar eclipse, as observed in England, Nova Scotia, Pennsylvania, and Newfoundland on June 24, 1778. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In 1878, there was an American eclipse expedition to view a solar eclipse in the western United States, as described in several new books, including American Eclipse by David Baron. French artist, astronomer, and amateur entomologist Étienne Trouvelot (1827–1895), fresh from accidentally releasing gypsy moths (which have been destroying millions of hardwood trees in the U.S. ever since), had decided to return to art. His set of chromolithographs of astronomical scenes included the 1878 total solar eclipse. We can tell that the eclipse took place near solar minimum, the period of least solar activity in the 11-year solar cycle, because in his detailed images, the large coronal streamers appear only near the equator, making it possible to see radial plumes near the poles. We expect a similar coronal configuration at this year’s solar eclipse, since we are again approaching solar minimum.

Solar eclipses in the U.S. have attracted many American astronomers to view them, even if solar observations were not their forte. This was the case for Edwin Hubble (1889–1953), who became famous for discovering that the spiral nebulae were galaxies outside the confines of our own and that distant galaxies were receding at a rate correlated with their distances—later interpreted as a sign that the universe is expanding. In 1923, the year before he discovered a Cepheid variable star in the Andromeda spiral nebula and used it to show that the nebula was actually a distant galaxy similar to our own, Hubble went on an expedition to Point Loma, California, to observe a solar eclipse. The Huntington has a photo of him seated near a telescope and puffing away on his trademark pipe.

U.S. astronomer Edwin Hubble on an expedition to Point Loma, California, to view the 1923 solar eclipse. Image courtesy of the Observatories of the Carnegie Institution for Science Collection at The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In 1925, scientists from the Mt. Wilson Observatory traveled to Connecticut to view a total solar eclipse in winter, as captured in another photo from The Huntington’s collection. A hundred years ago, the equipment used to capture large solar images on film often included a telescope with long focal lengths. Today’s electronic detectors are a hundred times more sensitive and make more finely resolved images much more quickly.

This year’s total solar eclipse will no doubt extend our knowledge and appreciation of our closest star, and may also spur interest in objects such as those at The Huntington that document a fascination that has lasted for centuries.

Scientists with their large telescopic cameras at the Mt. Wilson Observatory’s expedition site in Connecticut for the 1925 solar eclipse. Photo by the U.S. astronomer Edison Pettit (1889–1962), after whom a crater on the moon and a crater on Mars have been named. Image courtesy of the Observatories of the Carnegie Institution for Science Collection at The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

From Aug. 18 through Aug. 29, The Huntington will display, in the East Foyer of the Library’s Main Exhibition Hall, items related to eclipses from The Huntington’s holdings in the history of astronomy.

Jay M. Pasachoff is Field Memorial Professor of Astronomy at Williams College and a Reader at The Huntington. He is also the chair of the Working Group on Solar Eclipses of the International Astronomical Union and former chair of the Historical Astronomy Division of the American Astronomical Society, as well as the author of the Peterson Field Guide to the Stars and Planets.