The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

The Rise of the Newspaper

Posted on Thu., Oct. 12, 2017 by and

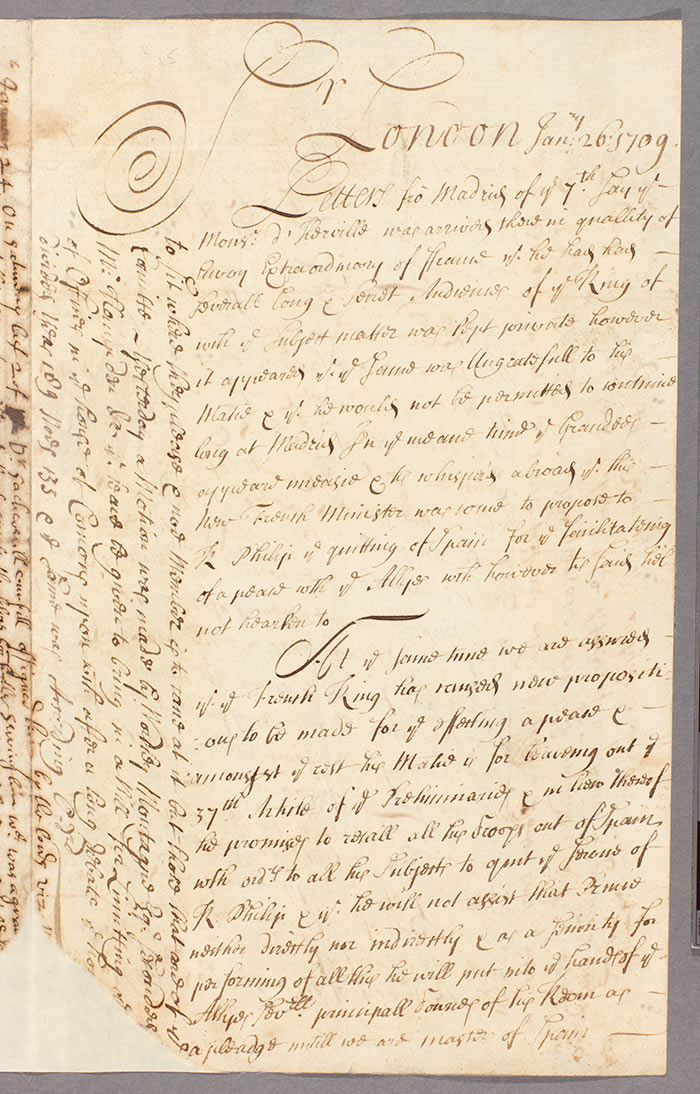

Manuscript newsletters from London, 1689–1710. Huntington Manuscript 30659, f. 115. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Between 1600 and 1900, the newspaper began to occupy a central position in the modern societies of Europe and North America. These publications helped make information current and critical, legitimate and public. They served as the focal point of daily reading, as the frame for opinion-gathering and opinion-making, as the inevitable site of publicity.

To explore the emergence of the newspaper and its eventual monopoly on public information, we have organized a conference titled “The Rise of the Newspaper in Europe & America: 1600–1900.” The Huntington Library has major holdings in periodical writing—both newspapers and journals—from 17th-century manuscript “news-letters” to the mass circulation dailies of 19th-century Britain and the United States. The conference will take place on October 13 and 14, 2017, in The Huntington’s Rothenberg Hall.

It is only now, in the early 21st century, with the newspaper’s gradual but steady loss of dominance, that we are finally beginning to calculate our debt to it and see more clearly its historical trajectory. By going back to the epoch when the newspaper rose to media centrality—aided by new printing technologies, the postal system, the railroad, and the telegraph—we can better understand the basis of its importance and value and its widespread impact, both positive and negative.

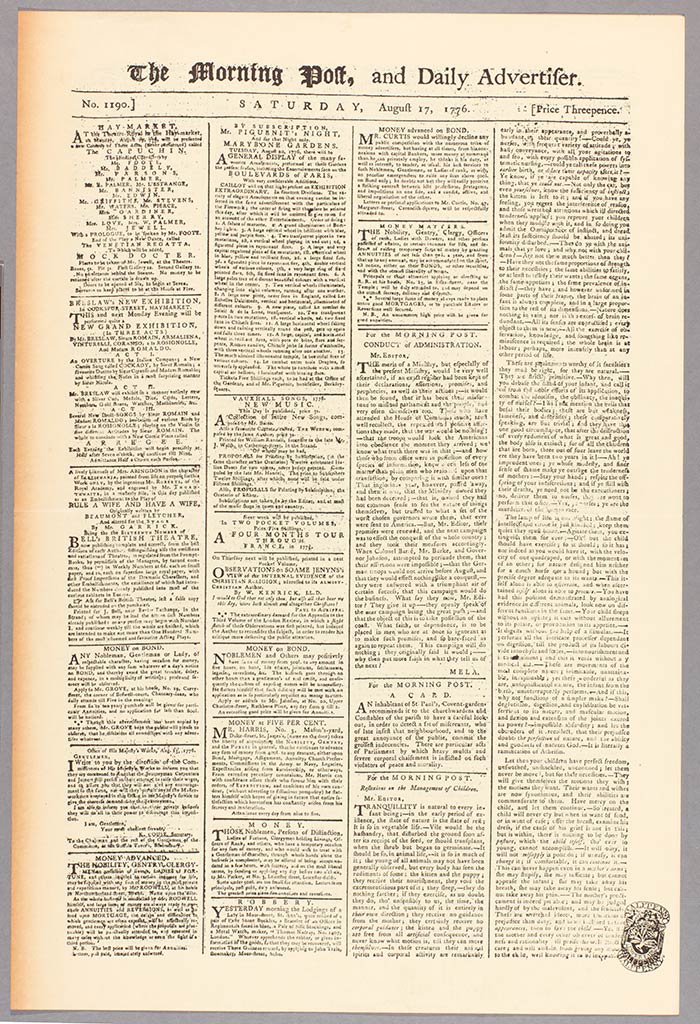

The Morning Post, and Daily Advertiser, No. 1190, August 17, 1776. London: Printed by R. Haswell. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Here are a few of the topics that our conference will explore.

The Newspaper’s Invention

Although many early print forms, from royal proclamations to broadsides and ballads, transmit news in an occasional way, the newspaper is characterized by reliable, periodic publication. How is the newspaper at its origins linked with commerce, politics, and events of enormous consequence, including the American and French Revolutions? Is the newspaper’s claim to truth fundamental or specious? How is it implicated in one of its most familiar features, the advertisement? And how did readers deal with the introduction of the newspaper, which, according to the scholar Andrew Pettegree, “offered what must have seemed like random pieces from a jigsaw, and an incomplete jigsaw at that.”

Fashioning the Reader Interface

Over its long history, newspapers went from a two-column to an eight-column layout; introduced the headline; pushed ads off the front page; systematized the byline; and then incorporated more and more subgenres, such as book reviews, human-interest stories, excerpts from books, and advice columns. Then, with the penny press, they became pocketable and inexpensive. What were the factors that produced the changing face and steady expansion of the newspaper?

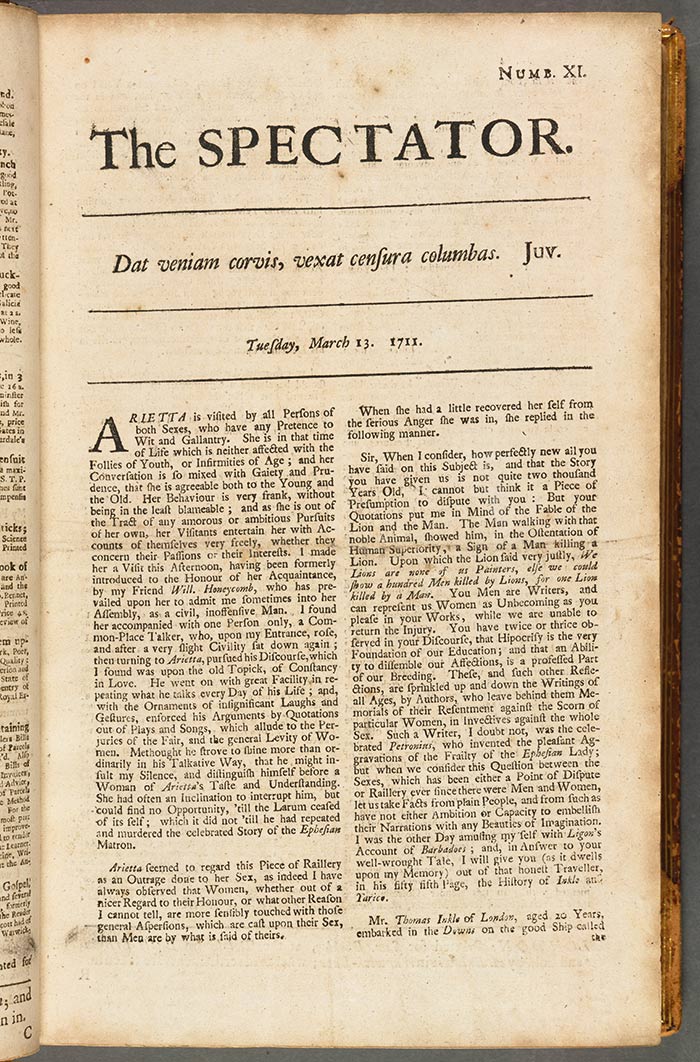

The Spectator, London, England, March 13, 1711. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Sensation vs. Objectivity

ISIS videos are just the latest examples of the news appeal of gruesome acts and disasters of all kinds. While crime and collective disasters were present in the earliest newspapers, the introduction of the telegraph and the news services that used it allowed disasters from around the world to become part of the daily read. Charles Dickens, among others, condemned this aspect of 19th-century American newspapers. Have newspapers—perhaps in some eras more than others—engendered a sense that we live in uniquely dangerous times? On the other side of the spectrum, how should we understand the newspapers’ mid-19th-century turn from partisanship to “objectivity”?

Readers as Agents and Consumers

Newspapers have a complex and inconsistent relationship with their readers. They both influence and reflect public opinion. They may welcome reader participation (letters to the editor) or exclude it (by race, gender, class, and overt censorship). Does the newspaper build or damage community? Does it create “imagined communities” or foster social fragmentation? How can the serious aims of newspapers (such as criticism of culture) be reconciled with their use primarily as entertainment?

The goal of the conference is to foster dialogue among scholars of the newspaper from history, literary studies, and media studies. Can the historical study of the newspaper give us terms with which to parry strident accusations of “fake news”?

William Warner is professor of English at UC Santa Barbara.

Rachael Scarborough King is assistant professor of English at UC Santa Barbara.