The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Religious Affections in Colonial North America

Posted on Wed., Jan. 25, 2017 by and

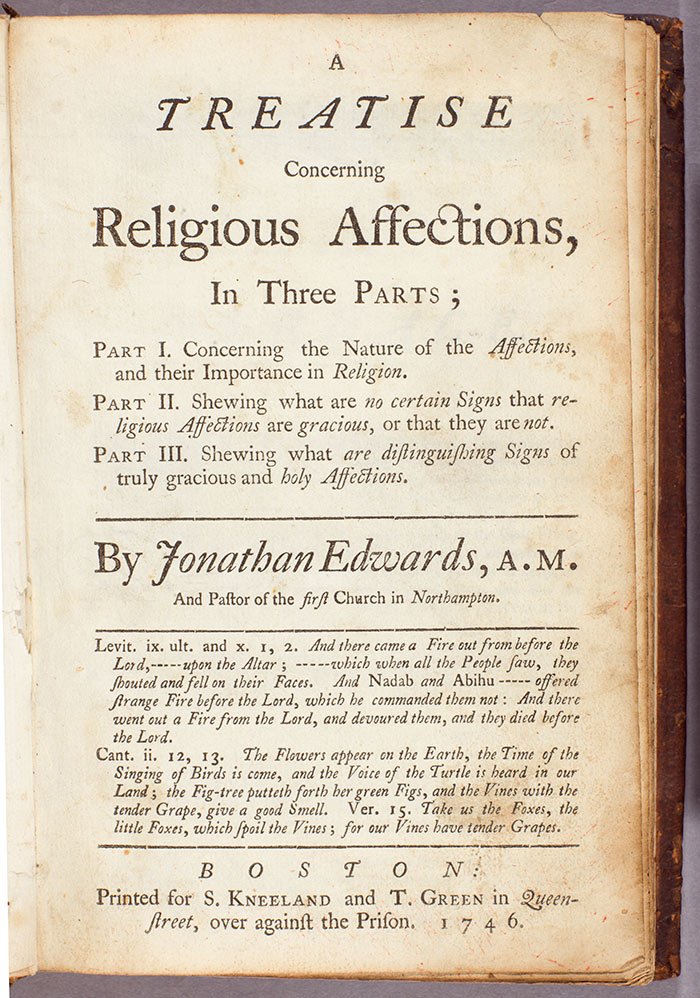

During the midst of the Great Awakening, the preacher, theologian, and philosopher Jonathan Edwards attempted to delineate true religious affections from false impressions and emotions. Title page of A Treatise Concerning Religious Affections, 1746, by Jonathan Edwards. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In 1746, Jonathan Edwards—the famous preacher, theologian, and philosopher of the Great Awakening—tried to sort through the wide variety of experiences that doubt and faith can generate. Some experiences should be trusted as signs of grace, he argued; others, less so. Either way, Edwards remained emphatic about the importance of religious affections. A true convert, according to Edwards, doesn’t just understand God, but actually experiences sorrow for sin, joy at forgiveness, and love for God and others. “True religion,” he insisted, “in great part, consists in holy affections.”

The work that Edwards produced, A Treatise Concerning Religious Affections, was arguably one of the most influential and well-known attempts to puzzle out these questions. But religious affections were vital not just in evangelical circles. They shaped communities throughout colonial North America in ways that have had an abiding influence upon American cultures and histories. The goal of our conference “Religious Affections in Colonial North America,” which will take place on Jan. 27 and 28 in Haaga Hall, will be to understand religious affections better by studying the diverse range of experiences, interpretations, and consequences they entail.

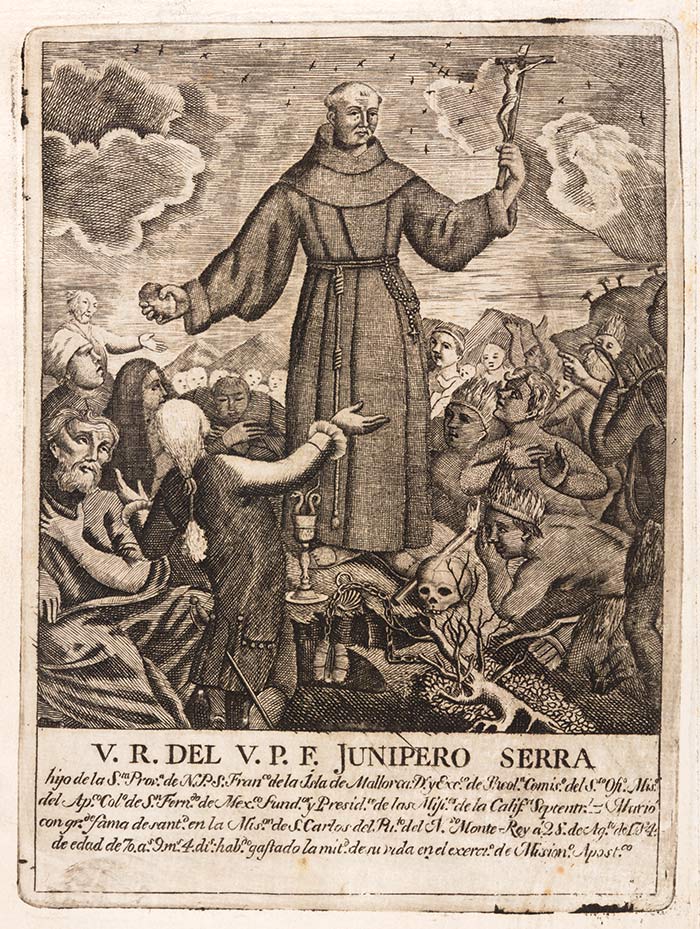

What and how people were moved—and to what end—were central to the experience of religious affections. Here, the Franciscan friar and missionary Junípero Serra, recently and controversially canonized by the Catholic Church, preaches to a crowd of Native Americans holding a stone in one hand and a crucifix in the other. Frontispiece of Relacion Historica, 1787, by Francisco Palou. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Studying religious affections brings together exciting developments from multiple fields. When considering the cultural history of affections, recent work in Early American Studies has attended to the watershed of the American Revolution, a moment when sensibility and sympathy primed disparate colonists for democratic citizenship. Democracy emerged from, and then demanded, a revolution in public intimacy—requiring, producing, and policing the capacity to feel properly in the new republic.

Yet Early American Studies has also seen a surge in scholarship that takes seriously the sincerity, importance, and persistence of religion as a dynamic repertoire of cultural practices. Lived religion changes, adapts, and grows both within and alongside the seeming rise of a secular society. Rather than being displaced by modernity, religion inflected colonial shifts in politics, economics, and art. In particular, religion—like public intimacy and sensibility—was instrumental in defining community and engendering radical change, including in the spiritual lives and performances of marginalized persons. Our conference brings these trends together to consider a longer cultural history of religious affections in early America.

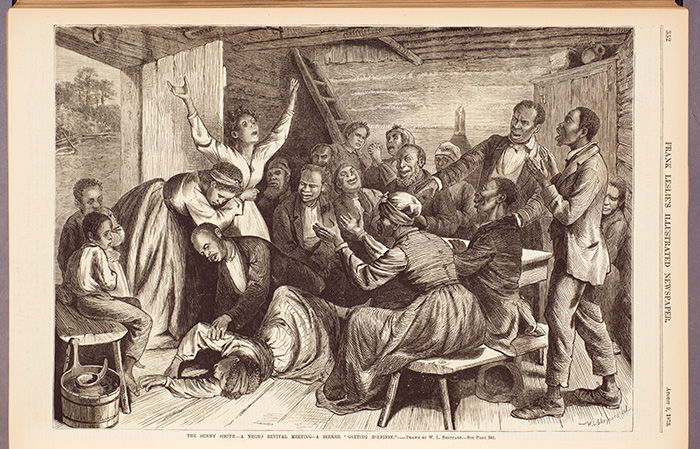

Great Awakening transformations, long acknowledged to have democratized religious access and authority, resonate with the spiritual lives and performances of marginalized persons, including slaves, indigenous peoples, and women. “The Sunny South—A Negro Revival meeting—A Seeker 'Getting Religion',” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, Aug. 9, 1873 issue, page 352. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

One goal for the conference will be to arrive at a better definition of “religious affections.” Affect, sympathy, sensibility, friendship, intimacy: these keywords have been theorized and historicized by many scholars. But what happens when religion enters the picture—especially in an age formerly designated the foundational moment of secularization? Are religious affections primarily concerned with communal values and public interactions, or are they about personal and private experiences between a believer and his or her deity (or deities)? When and how do different religions enfold tenderness, desire, protectiveness, and kinship, and how do they delineate between the mundane and the spiritual, the sensuous and the cerebral?

The conference is framed by opening and closing plenaries that speak to the larger field of American religious history and the study of emotions. The opening speaker is Marilynne Robinson, a Pulitzer Prize–winning author and expert in Calvinist traditions, who will speak on Jonathan Edwards. The sessions then move through a series of regionally focused topics: New Spain, Evangelical New England, New France, the Indigenous Atlantic, and the Early South. These sessions explore the wide possibilities of religious affections in multiple communities of colonial North America.

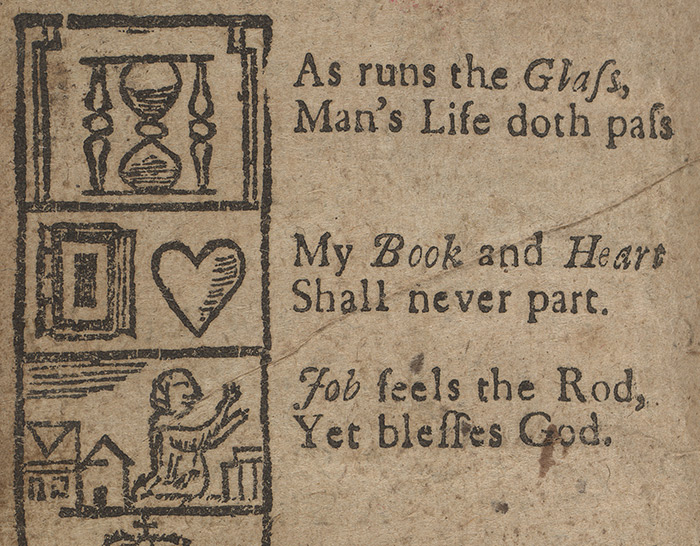

Instruction in religious affections began in childhood in the New England colonies. First advertised in 1690, The New-England Primer was a popular schoolbook for decades and it taught Puritan beliefs along with literacy. The picture alphabet offered memorable rhymes, including the central one above about the Bible and the heart. Detail from The New-England primer, enlarged: for the more easy attaining the true reading of English, 1735. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Taken as a whole, this conference will enable us to consider more deeply the meaning of “religious affections”: what, after all, makes some emotions count as “affections,” and what distinguishes some affections as “religious”? Moreover, how does religion—with its institutional structures, its ways of giving purpose and meaning to individual lives, its function in forming communities, and its dimensions of transcendence—speak back to and alter our received histories of emotions? To draw our discussion together, therefore, we conclude with a plenary by one of the foremost scholars of religion and the history of emotions, Barbara Rosenwein, who will speak to the larger interpretative dilemmas and consequences of studying religious affections.

You can read more about the conference program and registration on The Huntington’s website.

Caroline Wigginton is assistant professor of English at the University of Mississippi.

Abram Van Engen is associate professor of English at Washington University in St. Louis.