The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

To Paint without Thinking

Posted on Wed., Oct. 18, 2017 by

The exhibition “Frederick Hammersley: To Paint without Thinking” runs from Oct. 21, 2017, to Jan. 22, 2018, in the Susan and Stephen Chandler Wing of the Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art. Co-curated by James Glisson¸ the Bradford and Christine Mishler Associate Curator of American Art at The Huntington, and Alan Phenix, scientist at the Getty Conservation Institute, the exhibition is accompanied by a catalog from which this excerpt is taken.

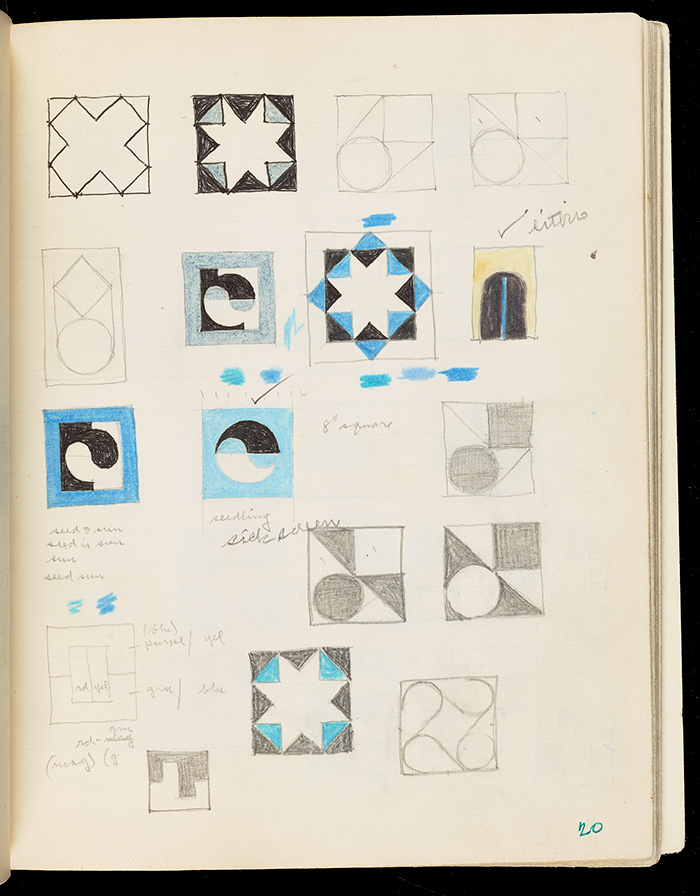

Frederick Hammersley (1919–2009), Study for Seedling, #4 1967, Page 20 of Notebook #3, Bound fabric-covered sketchbook with graphite and ink, 8 1/16 x 6 1/2 in. Getty Research Institute. Copyright Frederick Hammersley Foundation.

Frederick Hammersley (1919–2009), a longtime resident of Los Angeles and later of Albuquerque, is best known for his geometric paintings, which the critic Jules Langser in 1959 grouped with other works he called “hard edge” paintings. The elegant simplicity of Hammersley’s paintings, however, was the result of a rigorous process of refinement, worked out in a set of sketchbooks and archival materials now at the Getty Research Institute. These Notebooks, as he designated them, reveal him running through possibilities until he happened upon the solution.

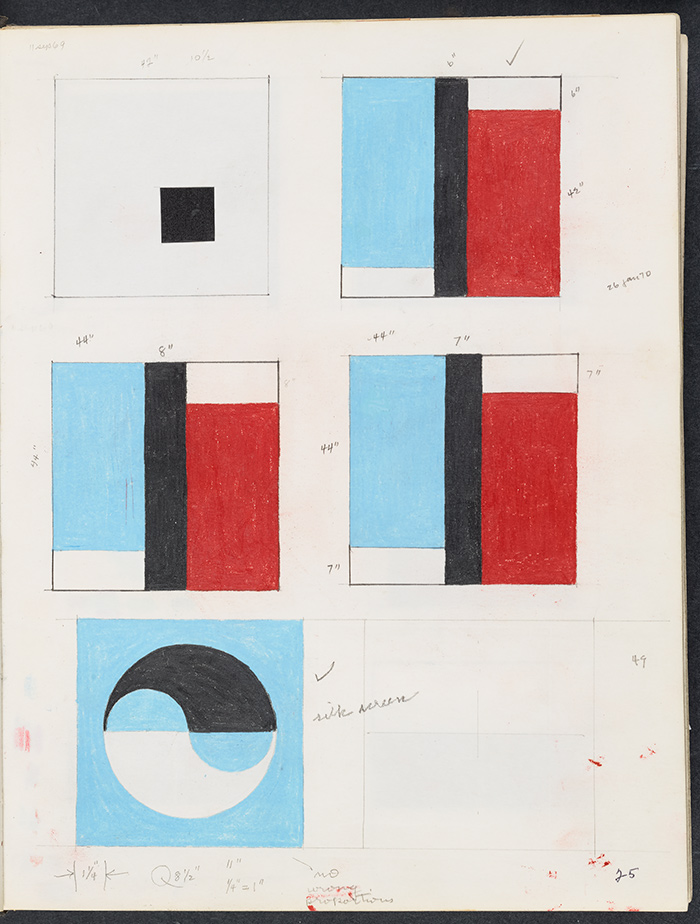

Frederick Hammersley (1919–2009), Studies for Adam & Eve, #2 1970, and Seedling, #4 1967, Page 25 of Composition Book, Sketchbook with graphite and colored pencil, 10 7/8 x 8 1/4 in., Getty Research Institute. Copyright Frederick Hammersley Foundation.

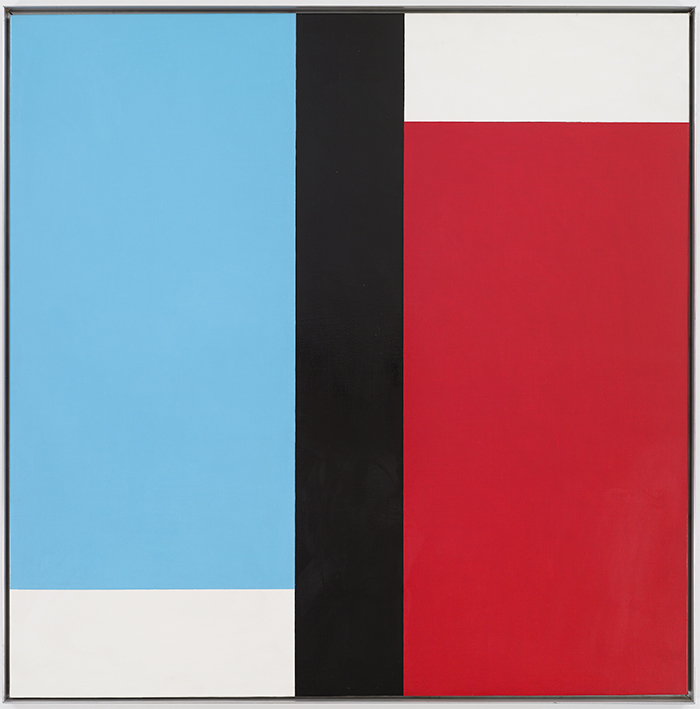

The page where he tests out options for the composition of Adam & Eve shows that he used the Notebooks to resolve the precise geometric composition and to establish a basic color scheme, which he fine-tuned later as he mixed and applied paint. Although he still had to make choices as he executed his paintings, the studies in the Notebooks, like a set of instructions, largely guided him. By figuring out the big decisions before he began the paintings, Hammersley could sit down and focus on applying the paint with a palette knife to achieve his fantastically crisp edges, which he did by hand without the aid of masking tape. In the “geometrics,” as he called his geometric paintings, he could “paint without thinking” because the thinking, so to speak, had been done in the Notebooks. The questions of what to paint was settled, and he had to worry only about the how.

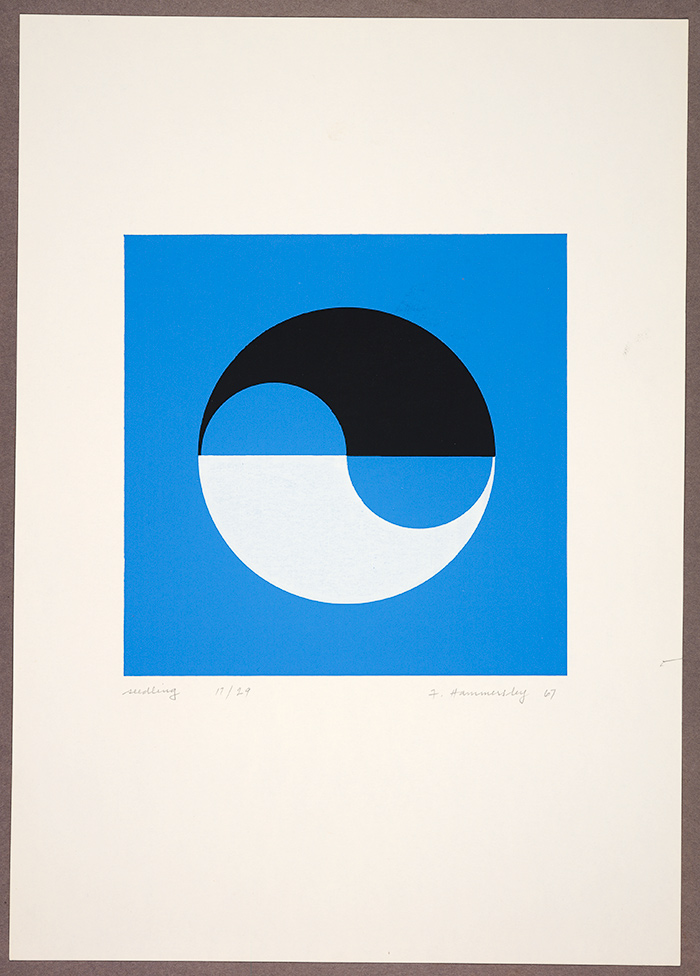

Frederick Hammersley (1919–2009), Seedling, #4 1967, Screenprint, ed. 17/29, Sheet: 17 x 12 in. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, Gift of the Frederick Hammersley Foundation. 2015.10.26. Copyright Frederick Hammersley Foundation.

When I first saw the Hammersley archival material at the Getty in January 2014, I immediately wanted to organize an exhibition around it. On that afternoon I looked, in a rush, through hundreds of small lithographs, examined dozens of color swatches, leafed through the artist’s Notebooks, and passed my eyes over his sheets of titles. The sheer quantity of materials and the evident care the artist had lavished on creating and preserving them impressed on me that they were neither mere records nor material ancillary to his paintings. This exhibition is the first to highlight the archival trove Hammersley left in his home/studio at the time of his death, and to argue from its abundant evidence that the artist was profoundly concerned with the process by which he created artworks—the technical elements he used (canvas, paints, and varnishes and their application) and the decision making, all the choices that, little by little, bring an artwork into the world.

Frederick Hammersley (1919–2009), Adam & Eve, #2 1970, Oil on linen on Masonite, 44 x 44 in., Collection Palm Springs Art Museum, Gift of L.J. Cella and museum purchase with funds derived from deaccession funds. Copyright Frederick Hammersley Foundation.

To complement the exhibition, The Huntington has published Frederick Hammersley: To Paint without Thinking, an illustrated catalog edited by James Glisson, with contributions from Alan Phenix, scientist at the Getty Conservation Institute; Kathleen Shields, executive director at the Frederick Hammersley Foundation; and Nancy Zastudil, administrative director at the Frederick Hammersley Foundation. The catalog is available for purchase online at the Huntington Store.

The presentation of the exhibition “Frederick Hammersley: To Paint without Thinking” at The Huntington has received generous support from the Frederick Hammersley Foundation and the Susan and Stephen Chandler Endowment for Exhibitions of American Art. The exhibition catalog has received generous support from the Frederick Hammersley Foundation.

James Glisson is the Bradford and Christine Mishler Associate Curator of American Art at The Huntington.