The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Our Own Dawson City

Posted on Thu., Sept. 28, 2017 by

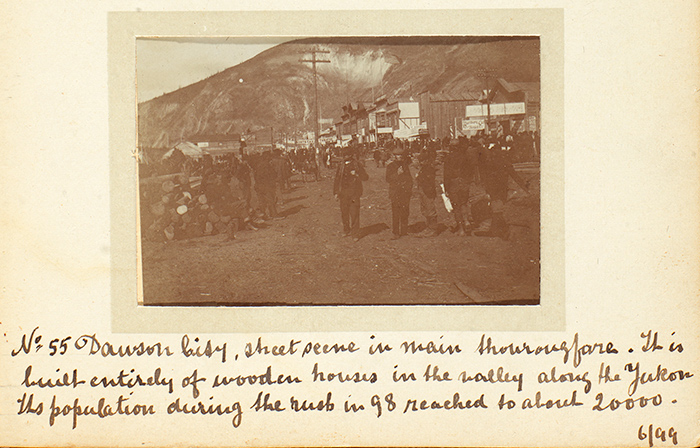

Detail of a page from Alfred and Charles O’Meara’s photograph album showing a street scene in the bustling boomtown of Dawson City, June 1899. Unidentified photographer. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

When creative filmmakers set their sights on illuminating neglected corners of history, magic can happen. Such is the case with Bill Morrison’s riveting new documentary Dawson City: Frozen Time, which weaves a story about the interconnections between Hollywood and the Klondike gold rush boomtown—prompted by the 1978 discovery of a huge stash of silent films preserved in permafrost in a buried municipal swimming pool. As I watched the movie and realized that its story intersected with The Huntington’s collections, its magic cast an even more powerful spell. I could hardly wait to get back to the Library’s archives to take a fresh look at our own trove of photographs of Dawson City.

The 1896 discovery of gold in Rabbit Creek—a tributary of the Klondike River in Yukon Territory, Canada—set off the fabled Klondike gold rush. Within a few months, an estimated 100,000 prospectors began traveling north with visions of glittering yellow ore and riches beyond their imaginations.

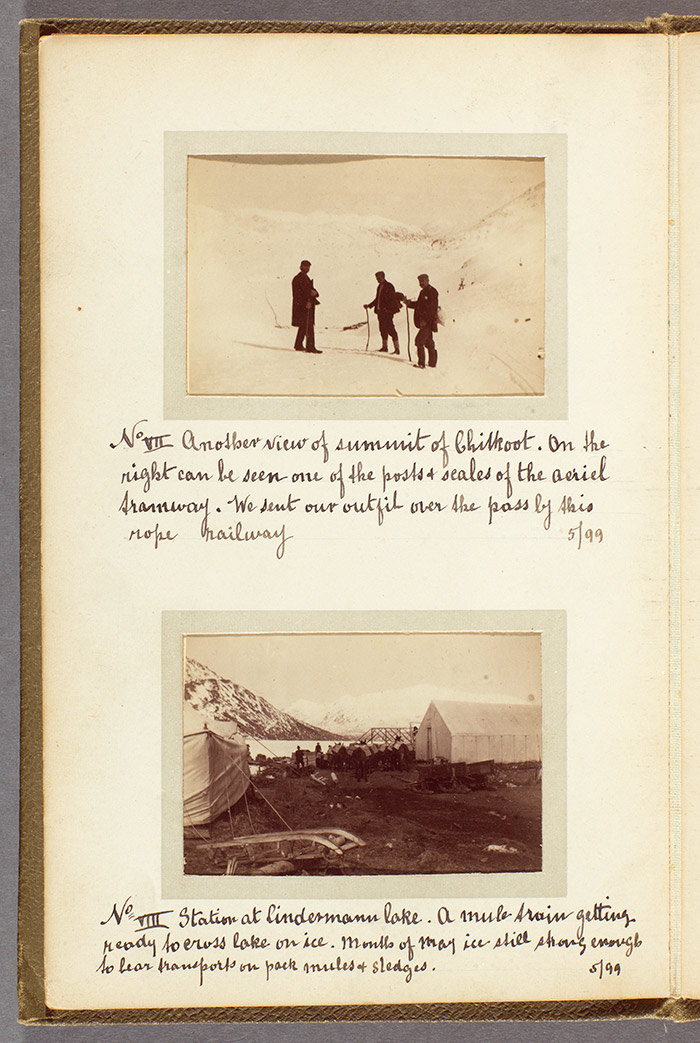

A page from Alfred and Charles O’Meara’s photograph album showing the men on the summit of the hazardous Chilkoot Pass and at Lake Lindeman, May 1899. Stampeders tackled the pass by climbing the so-called “golden staircase,” 1,500 steps carved into the snow and ice. At the end of the pass was Lake Lindeman, near the headwaters of the Yukon River. Unidentified photographer. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The first archival nugget I retrieved was a photo journal compiled by a pair of intrepid prospectors, Alfred and Charles O’Meara, during a grueling 600-mile trek from Dyea, Alaska, through the Yukon territory of Canada that ended at Dawson City. It was 1899, at the height of the gold rush, and the city’s population had swelled to between 30,000 and 40,000.

In a series of 49 small format, amateur photographs with neatly handwritten captions, the album records the determined stampeders’ adventures through steep mountain passes, across treacherous lakes, and down river rapids before they finally reached Dawson City, on whose outskirts the pair staked their apparently unsuccessful claim.

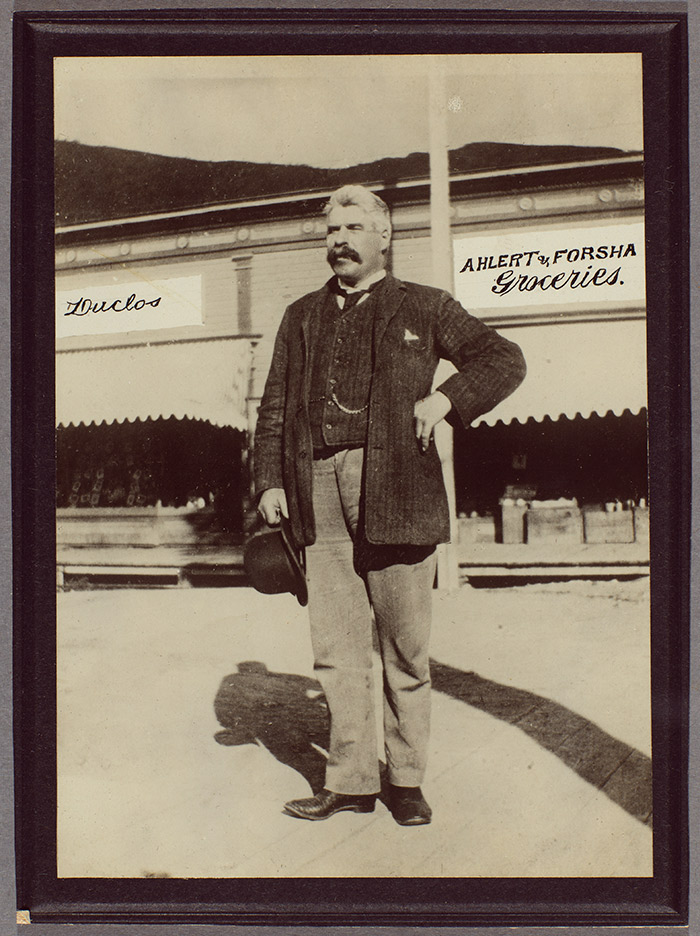

This photograph likely depicts J. H. F. Ahlert and C. L. Forsha in their Ahlert & Forsha grocery store in Dawson City in 1910. Unidentified photographer. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

While researching this photo album, I made a surprising discovery. The Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library has a nearly identical photo album in their collections. In fact, it was through their copy that I learned Alfred and Charles’ surnames, since, curiously, the handwritten title page of Yale’s album is signed while The Huntington’s is not. I find it intriguing that there would be two near-identical copies of the same album, each with meticulously handwritten captions. (But that’s a mystery to be solved at another time.)

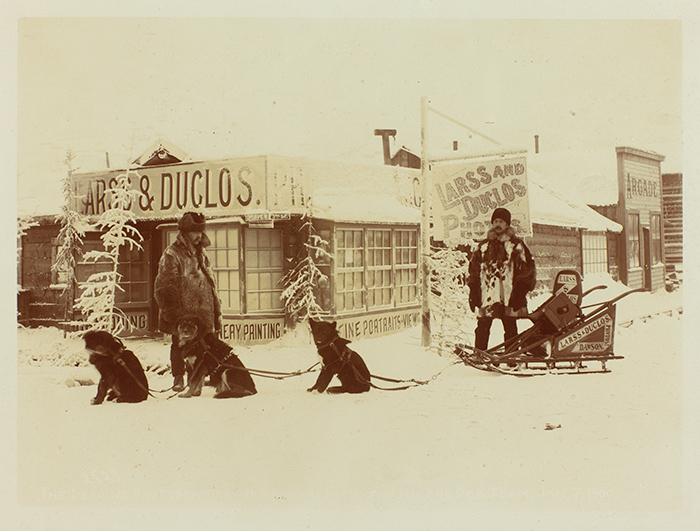

Continuing on my armchair Yukon adventure, I arrived next at our collection of mainly commercial photographs, compiled by Dawson City grocer John H. F. Ahlert. While the O’Meara photo album presented a private perspective, this collection of 55 larger format images shows many of the same locations at the same time-period from the viewpoint of professional photographers, including Eric Hegg, P. E. Larss, and Joseph Duclos. The publication of such extraordinary images by these and other photographers helped burnish the legend of the Klondike “stampede” that had already gripped the national imagination. Among the images of the colorful characters inhabiting Dawson City is an informal portrait of the dashing millionaire Alexander “Big Alex” MacDonald, known as the “Gold King of the Klondike.”

Alexander “Big Alex” MacDonald in Dawson City, ca. 1900. Known as the “Gold King of the Klondike”, MacDonald made millions during the Gold Rush yet died in 1909 in a small cabin in Dawson City, alone and in debt. Unidentified photographer. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Naturally, this being the Huntington Library, these two collections hardly encompass the entirety of our Klondike gold rush material. Among many other items, there are rare books, such as Alaska and the Klondike gold fields…Practical instructions for fortune seekers (ca. 1897); the diary of one J. Franklin Zimmerman, detailing his 1898 fortune-seeking journey to Dawson; and a folding map from 1897, showing the most direct routes from San Francisco to Alaska and the Klondike.

As recounted in Morrison’s film and elsewhere, most of the prospectors came back empty-handed. The Huntington holds the papers of one of the most celebrated of these unsuccessful gold seekers, Jack London (1876–1916). He set out for the Klondike with hopes of striking it rich. He returned home with a treasure of another sort—the inspiration for many of his most celebrated books and short stories, including White Fang and To Build a Fire. And The Huntington is that much richer for it.

Joseph E.N. Duclos (1863–1917) and Per Edward Larss (1863–1941) in front of their Dawson City photography studio, with dog team and Larss & Duclos sled, around 1898. Unidentified photographer. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Anita Weaver is a curatorial assistant in the Library’s curatorial department.