The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Medieval Manuscripts in the Digital Age

Posted on Tue., Aug. 4, 2015 by

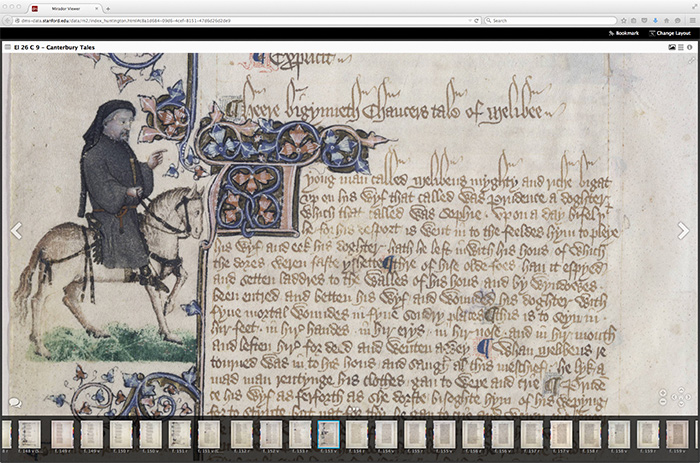

The Huntington’s Ellesmere manuscript of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, open to the first lines of “The Tale of Melibee,” as seen through the Mirador viewer. Along the bottom of the screen, you can see each image of the individual pages that comprise the volume. This feature makes it easy to scroll through images and zoom in on particular passages or illustrations.

The Huntington’s Ellesmere Chaucer, an illuminated manuscript produced around the year 1400, is the most handsome extant version of The Canterbury Tales in the world. Many scholars believe Geoffrey Chaucer oversaw some of its production. If you’ve ever read The Canterbury Tales, then chances are the version you read was closely based on this remarkable manuscript, which Henry Huntington purchased as part of the Bridgewater Library in 1917.

The Huntington has recently partnered with Stanford University and other rare book and manuscript repositories to make medieval manuscripts accessible in new ways. People can now view online seven of our most prized 15th-century medieval manuscript volumes—including the Ellesmere Chaucer and manuscripts by the poets John Lydgate and Thomas Hoccleve—through an enhanced viewer called Mirador. Through Mirador, you can scan thumbnail images of an entire text, read a single folio, or view images sequentially in book format. You can also zoom in on areas of interest and even tag parts of images to leave your own notes. (You can play around with a live demo version here. However, the notes feature is not active in this version.) Since Mirador is a global collaboration, you can use it to view hundreds of other medieval manuscripts from libraries around the world.

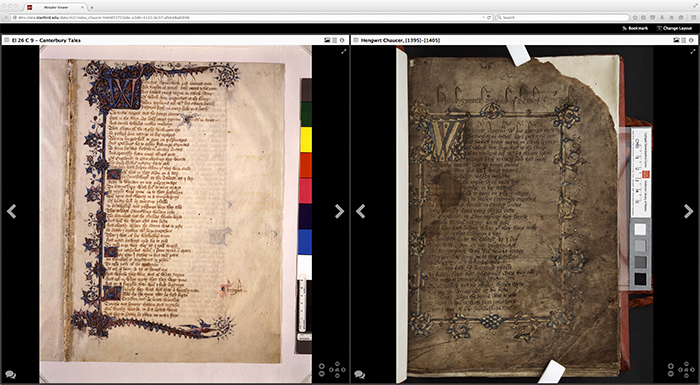

Side-by-side comparison of the first folios of the General Prologue to The Canterbury Tales. The image on the left is from The Huntington’s Ellesmere Chaucer; the image on the right is from the Hengwrt Chaucer at the National Library of Wales.

And that’s just the beginning! Benjamin Albritton, digital manuscripts program manager at Stanford University Libraries and one of the developers of this technology, says Mirador’s “specialty is comparison—across folios, objects, collections, and repositories.” Rather than trying to maneuver through the digital libraries of two different archives, each with its own unique navigational settings, readers using Mirador can use a single set of online tools to compare pages from different institutions.

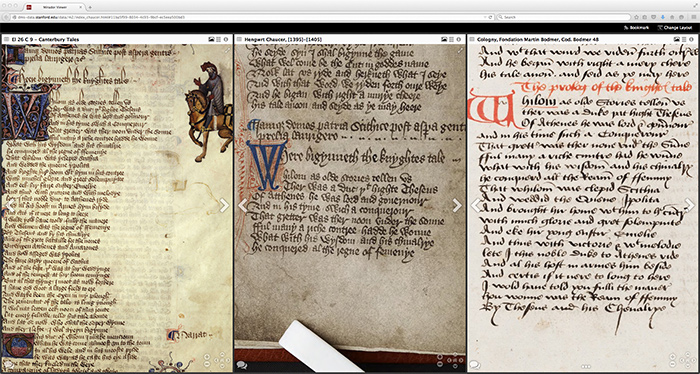

For example, the same 15th-century scribe who created The Huntington’s Ellesmere Chaucer also wrote another copy, the Hengwrt Chaucer, which is kept at the National Library of Wales. With the live demo, you can pull up the first folio of the Ellesmere manuscript and compare it side-by-side with the Hengwrt version; you can also zoom in and out or turn the pages to move through the volumes. Notice differences in the large opening initial? What about the first few lines of the text? What clues tell us that the same scribe wrote both versions? You can even add into the mix a third, late-15th-century version of The Canterbury Tales from the Fondation Martin Bodmer in Cologny, Switzerland.

Mirador is a free and open access source, which means anyone with an Internet connection can use the program. Researchers can now study these manuscripts in their offices; teachers can use them in their classrooms; and literary fans can sit in their pajamas at home and read the same pages of Chaucer that people have been reading for 600 years. These 21st-century technologies are making 15th-century manuscripts accessible to us all.

This screen-shot lines up the prologue to The Knight’s Tale from three copies of The Canterbury Tales. The image on the left is from The Huntington’s Ellesmere Chaucer; the image in the middle is from the Hengwrt Chaucer at the National Library of Wales; and the image on the right is from a late-15th-century version of The Canterbury Tales at the Fondation Martin Bodmer in Cologny, Switzerland.

For a more technical description of this program, as well as instructions on how to access the full version of Mirador and similar tools, read Benjamin Albritton’s post here.

Vanessa Wilkie is William A. Moffett Curator of Medieval and British Historical Manuscripts at The Huntington.