The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Enchanting Miniature Books

Posted on Wed., Aug. 23, 2017 by

Miniature books are among the hidden treasures at The Huntington. Henry E. Huntington did not set out to collect miniature books, but he received them as part of other large collections he purchased en bloc. By the 1990s, at least 1,000 miniature titles were part of the Library collection. In 1991, The Huntington received a gift of more than 7,000 miniature books from Monsignor Francis J. Weber, and the collection continues to grow. Laura Forsberg, assistant professor of English at Rockhurst University and a 2016–2017 NEH fellow at The Huntington, discusses the variety of The Huntington’s miniatures and speculates on why they fascinate us.

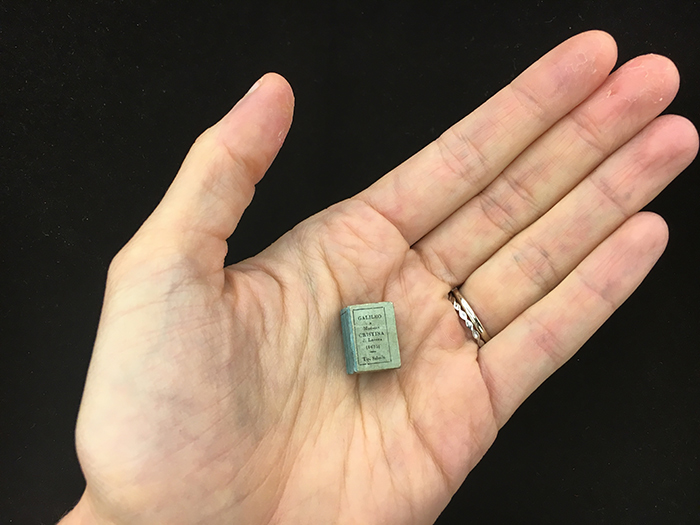

Galileo a Madama Cristina di Lorena, 1615, was printed in 1896 using 2-1/2-point fly’s-eye type. In a book half the size of a postage stamp, Galileo describes the nature of the heavens. Photo by Laura Forsberg. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

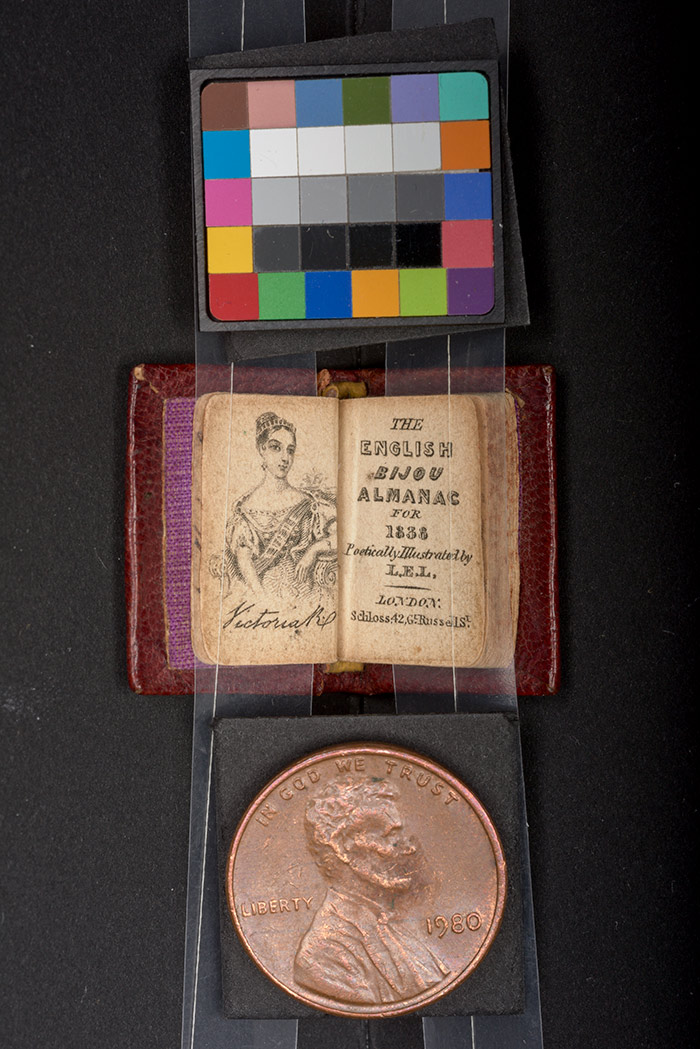

Imagine cradling in the palm of your hand a tiny book, measuring 3/4 by 5/8 of an inch. The entire volume is about the size of a penny and fits into a matching slipcase. As you gingerly open the tiny book, your eyes strain to read the italicized type, and you struggle to keep your fingers from blocking the print. Your hands feel massive in relation to the book, like clumsy instruments that are barely capable of the simple task of turning pages.

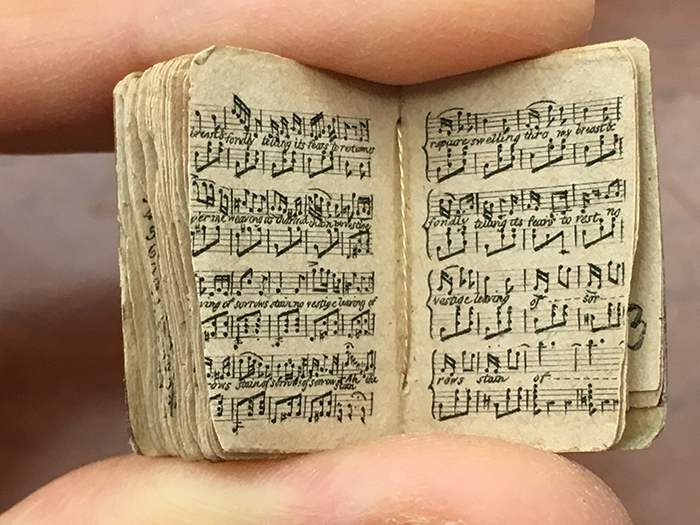

These were my feelings as I examined The English Bijou Almanac of 1837. The volume pairs a calendar of the year with a set of poems and engraved portraits depicting the poets Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772–1834) and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832), the scientist Mary Somerville (1780-1872), and the opera singer Maria Malibran (1808-1836), among others. The volume concludes with four pages of exquisitely printed sheet music. An opening poem captures the sense of dreamy reverie pervading the whole:

We dream no more that fairies dwell

In the white lily’s fragrant cell

And yet our little book seems planned

By elfin touch in elfin land

And sent by Oberon, I ween,

An offering to our English Queen.

The author of the poem is right. It’s hard to imagine that anyone but a fairy artisan could craft such a beautiful volume on this scale.

The English Bijou Almanac of 1837. Published by Albert Schloss. Photographing a volume of this size poses unique challenges. In order to take professional images of this and other miniature volumes, Huntington staff constructed a small cardboard stand and used a system of clear strips and conservation thread to hold the volume partly open. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

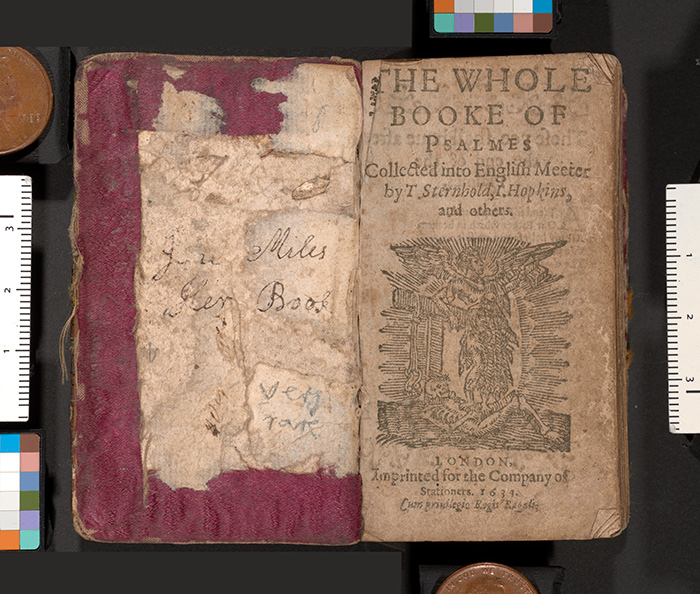

The English Bijou Almanac is one of more than 8,000 miniature books in The Huntington’s rare book collection, virtually all of which measure three inches or less in height. The collection is capacious in its scope; it includes a 1634 book of Psalms with an elaborate embroidered binding and a 1900 Paris Exhibition souvenir book in metal with tiny photographs of the city reduced to less than 3/4 of an inch. There is a 19th-century set of Shakespeare’s complete works in which each volume is decorated with a fore-edge painting of a great city in Europe, which appears only when you fan the pages. There is The Infant’s Library (ca.1800), a six-inch wooden box that is painted to resemble a full bookshelf and that contains a set of 16 children’s books. And there is a tiny Qu’ran, printed by the Glasgow publisher David Bryce in the early 20th century; similar miniature Qu’rans were given to many South Asian soldiers fighting with the British in World War I.

I became fascinated by miniature books a few years ago while thinking about scale and Victorian literature. Printers produced more than 3,000 unique miniature books during the 19th-century. Each volume required handset type; printers of the period competed internationally to produce the smallest possible type that would still print clearly and legibly.

Kern der Nederlandische Historie, 1753, with the foldout illustration of a national synod council. Miniature books often employ foldout illustrations, using the form of the publication to underline the expansiveness of the contents. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Why were these volumes produced? Who used them and how?

Publishers of miniature books explain their motives in simple terms, insisting upon the utility and portability of their books. As the editor of one miniature gazetteer explains, “[this book] may without the least inconvenience be made a constant companion to the pocket, even to the supplanting of a less instructing or useful occupant—the Snuff Box.”

But I find this answer unsatisfying. Miniature books are fragile and hard to use. The pages are too small to turn comfortably, and the type often hurts my eyes after I read for a few minutes. Children’s miniature books, which were particularly popular in the 19th century, don’t make any more sense. Children lack the mechanical dexterity to manipulate miniature books; for this reason, we typically print oversized children’s books today. So, despite the insistence of the gazetteer’s publisher, I can’t imagine a 19th-century gentleman abandoning his snuffbox in favor of a world atlas.

Title page of The Whole Booke of Psalmes Collected into English Meeter by T. Sternhold, J. Hopkins, and others, 1634. The title illustration shows an allegory of the triumph of religion over death. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

I found my answer in an unexpected place: in an 1896 book, measuring 11/16 x 1/2 of an inch, which contains a letter by Galileo to Madama Cristina di Lorena. The volume is printed using an extremely rare 2-1/2-point “fly’s eye” type. This type is famously almost impossible to use; the typesetters who first employed it permanently damaged their eyesight in the process. It’s also, as you can imagine, very difficult to read. And yet the object possesses an aura of captivating wonder. In a book half the size of a postage stamp, Galileo describes the nature of the heavens.

This, I’m convinced, is the true power and purpose of miniature books: to compress knowledge, seemingly by magic, into an enchanting miniature form. The owner of a miniature book dwarfs the volume and imaginatively possesses the knowledge it contains. A miniature book, in fact, suggests an infinity of minute space, a world of information that was intended to be carried in a pocket or kept in a locket around the neck.

Both in the 19th century and today, the reason for owning miniature books is rarely to read them. Instead, people cherish the experience of pure enchantment that comes when you gaze down at a fairy volume nestled in the palm of your hand.

A page of sheet music from the final Rondo of Balfe’s 1836 opera of the Maid of Artois. The lead role was written for Maria Malibran, whose portrait is featured in The English Bijou Almanack and who died just months before the volume was printed. The notes and lyrics, dancing across the page, imaginatively bring back the voice of the recently deceased artist. Photo by Laura Forsberg. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Related content on Verso:

Fairy Hunting at The Huntington (Jan. 11, 2017)

In the Library Exhibition Hall through October 2017, visitors to the exhibition “Remarkable Works, Remarkable Times” can see an example from our miniature book collection, a book of Psalms with a binding embroidered in silver thread. Look for it in the section titled “A Masterful Poem.”

Laura Forsberg is assistant professor of English at Rockhurst University and a 2016–2017 NEH fellow at The Huntington.