The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Early Modern Literary Geographies

Posted on Thu., Oct. 13, 2016 by and

“View of Wotton Underwood,” anonymous, 1565. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

One of the gems in The Huntington’s library collection is a 16th-century image titled “View from Wotton Underwood.” Although officially cataloged as a “map,” it’s quite different from what we usually call a map today. Offering a detailed and colorful point of view on a particular Buckinghamshire village, this map encompasses not only residences, but also what a geographer might term the local “taskscape,” indicating worked farmland and energy-generating windmills.

Such a view can provide valuable insights to cartographic historians, geographers, archaeologists, literary scholars, and social historians, among others. In this regard, the “View from Wotton Underwood” is an apt illustration for our interdisciplinary conference on “Early Modern Literary Geographies,” which will take place on Oct. 14 and 15 in Rothenberg Hall.

In recent decades, arts and humanities subjects have undergone what is often referred to as a “spatial turn,” drawing influences and ideas into their realms from such social sciences as cultural geography and architecture. At the same time, the social sciences have been enriched with ideas and methods from humanities subjects and creative engagements with poetry, fiction, and the visual arts. The field of "literary geographies" builds on these mutual interests. Scholars think in innovative ways about the literary representation of landscape, space, and place, and also about how space was conceptualized, imagined, and used.

Detail from the frontispiece of John Ogilby’s Britannia, 1675, drawn by Francis Barlow, engraved by Wenceslaus Hollar. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Our focus for the conference is on the late 16th and early 17th centuries in England, primarily, though also in the neighboring countries of Scotland, Wales, and Ireland. The early modern period was a time when new technologies for mapping, surveying, and navigation dramatically altered people’s understandings of the world in which they lived. Such changes occurred in the context of world travel and global exploration, which reached a new peak under the reign of Queen Elizabeth I. These changes also took place on the domestic front, as depicted in “View from Wotton Underwood.”

During the early modern period, London grew into a major capital city that was increasingly shaped not only by global trade, but also by its relationship to the regions and provinces that fed its ever stronger demand for human and material resources. (The representation of London in John Ogilby’s Britannia (1675), the first modern road atlas, demonstrates both the city’s centrality to an emerging nation as well as its place within a national travel network.) The growth of the metropolis inevitably led to transformations in conceptions of space and place, as London’s citizens, many of them migrants to the city, sought to make sense of the sometimes heady, sometimes alienating experience of living cheek by jowl with each other.

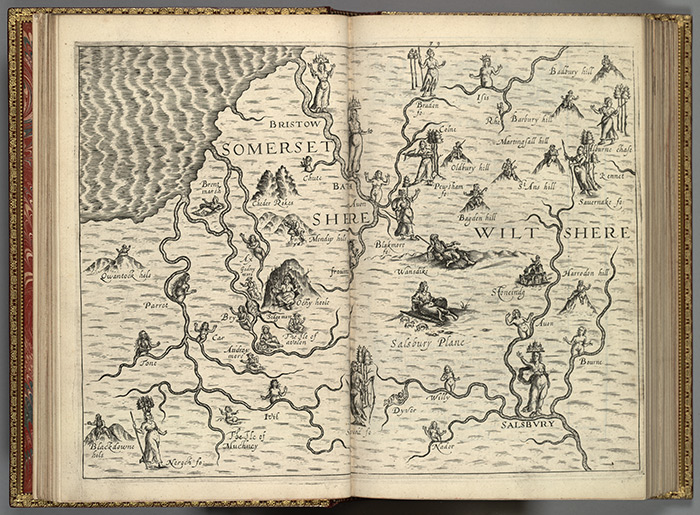

Map indicating rivers in Somerset and Wiltshire counties from Michael Drayton’s Poly-Olbion, 1613. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The conference is organized under four major headings—body, household, neighborhood, and region. We see each of these four terms as a crucial spatial concept. We move out from the individual self to think about how identity was shaped and formed by the specific places, spaces, buildings, habitats, and communities in which people lived, worked, and experienced the world.

We have invited conference participants—historians, geographers, experts in literature and archaeology, and scholars of performance studies—to explore a capacious understanding of early modern space and place, one that embraces rural and provincial communities as much as metropolitan ones and which works on very different scales and sizes. We have urged presenters to think about households from the grandest estate to the humblest cottage or tenement. And we have asked them to think through the importance of such habitats as forests and fens—as well as waterways, rivers, and oceans—as they tell the stories of how early modern people lived, imagined, and felt.

For us, literary geographies in their early modern incarnation are about moving through as much as dwelling in space and place, and we expect concepts such as mobility and enactment, embodiment and experience, to feature prominently in our conference discussions.

You can read more about the conference program and registration on The Huntington’s website.

Julie Sanders is pro-vice-chancellor for the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences and professor of English Literature and Drama at Newcastle University.

Garrett A. Sullivan, Jr., is liberal arts research professor of English at Pennsylvania State University.