The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Early Modern Collections in Use

Posted on Thu., Sept. 14, 2017 by

Title page of Museum Britannicum, London, 1778, which contains illustrations of some of the natural and artificial wonders collected by Hans Sloane (1660–1753), a physician and president of the Royal Society. Sloane’s famous collection became the foundation of the British Museum. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In the first half of the 18th century, Hans Sloane (1660–1753)—the collector, physician, and president of the Royal Society—was the acknowledged center of a web of international relationships that brought objects, letters, and visitors into his house in the London suburb of Chelsea. He was recognized by scholars across Europe and the Americas as one of the great collectors of his era, and after his death, his collection of natural history objects, artifacts, books, manuscripts, and prints and drawings was purchased by the British government to found the British Museum.

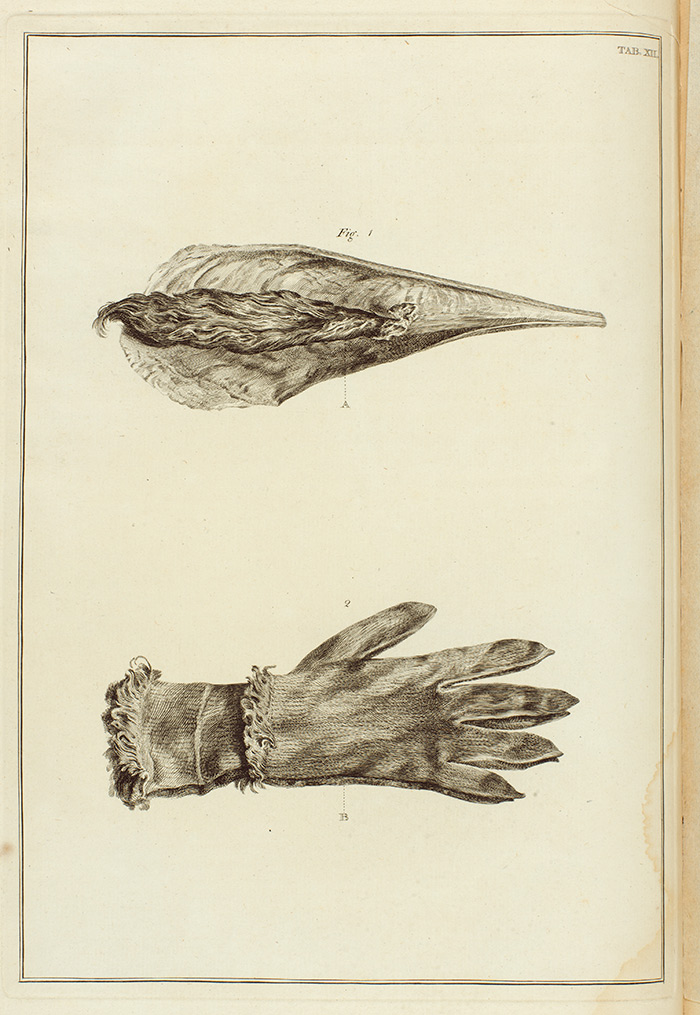

Sloane, who lived to the age of 93, is often seen as a transitional point from an older idea of encyclopedic collecting and the more systematizing collections of the Enlightenment, evident from the fascination shown well after his death with a curiosity like the glove in the British Museum made from the “beard” of a shell, Pinna marina, in a work publicizing the museum. Over the last five years, a research group in London has been concerned with bringing together the scattered manuscripts and collections of Sloane to understand better how his collection served as an intellectual, social, and cultural node not only in London, but also around the world. Scholars and doctoral students have worked together with curators at the British Museum, British Library, and Natural History Museum to develop questions about Sloane, his world, and his collections. This group’s work is the origin of the conference “Early Modern Collections in Use,” which will take place at The Huntington in Rothenberg Hall on September 15 and 16, 2017.

Illustration of a Pinna marina shell, with its “beard,” above a pair of men’s gloves made in Andalusia out of a Pinna marina beard. Jan and Andreas van Rymsdyk, Museum Britannicum, London, 1778, plate XII. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Historians of collecting have generally been interested in the people who formed collections and the objects they collected. What has been less studied is what happened in early modern collections and how they were used. What were collectors thinking about when they collected and arranged objects, or when they opened their collections to some visitors but not others? What made them publicize their collections or, conversely, hide some of their objects? What did visitors make of what they saw? What kind of behavior was appropriate in private or semi-public collections? What cultural significance did these encounters have? These are questions participants in the conference will examine, based on collectors from Samuel Quiccheberg in the 16th century to the 18th-century Sloane. Participants will also examine understandings of art collections as well as collections of horses and birds.

Albertus Seba, Locupletissimi rerum naturalium thesauri accurata descriptio (Accurate description of the wealthiest treasure of natural things), Amsterdam, 1734–65, Vol. I, part 1, second title page. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Sloane, for example, was well known for his generosity in showing his collections to interested visitors and for his centrality in the community of scholars known as the Republic of Letters. His name even appeared in guidebooks to London in the 18th century. His approval was sought by an enormous network of correspondents, among whom was the apothecary Albertus Seba in Amsterdam, whose large collection of natural history objects was published in four large volumes, copies of which are in the Library’s collection.

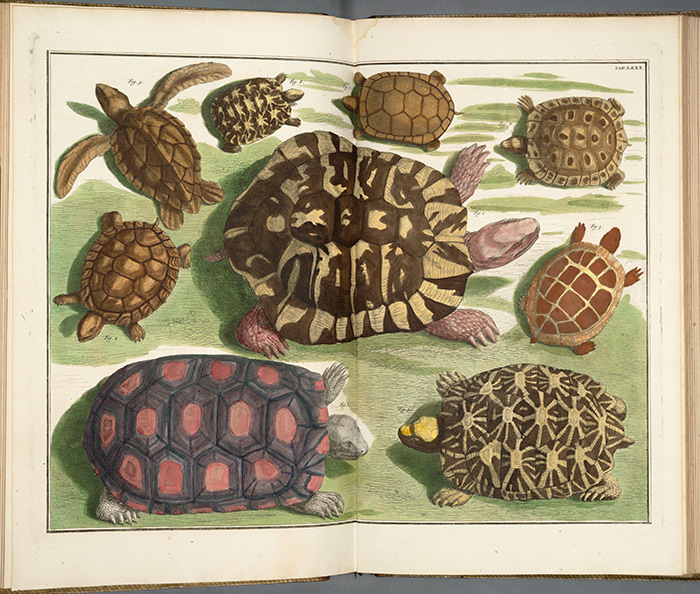

Large and small turtles from America, Ceylon, and Amboina in Albertus Seba's Locupletissimi rerum naturalium thesauri accurata descriptio (Accurate description of the wealthiest treasure of natural things), Amsterdam, 1734–65, plate 80, etching with watercolor. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Seba’s museum, which included wild animals he kept in his house and garden, was an obvious place of resort for other collectors and admirers of natural history. One of these was Sloane’s step-grandson Rose Fuller, who reported back that the collection was not nearly so large, varied, or interesting as Sloane’s. The first volume of the plates and text was presented to Sloane in part to curry favor with him as president of the Royal Society, one of several scientific societies into which Seba was attempting to gain entrance. The volume was part of a cultural performance on the part of Seba, one which was enacted particularly in person with visitors like the unimpressed Rose Fuller. We can see from examples like these that collections were important centers of social and intellectual interaction, systematization and rethinking of intellectual relationships, and cultural performance.

At the conference, those working on the Sloane project will join other prominent scholars of early modern collecting to explore freely what happened behind the walls of early modern collections. The conference will include a round table during which, among other things, participants will be able to engage with curators to discuss ways that the history of collecting can be made exciting for modern audiences.

An illustration of an early modern collection in A catalogue of the Portland Museum, lately the property of the Duchess Dowager of Portland, deceased: which will be sold by auction, by Mr. Skinner and Co. on Monday the 24th of April, 1786, Skinner and Co. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

You can listen to the conference presentations on SoundCloud. Funding for this conference has been provided by The Huntington's William French Smith Endowment and the USC-Huntington Early Modern Studies Institute.

Anne Goldgar is professor of Early Modern History at King’s College London and the author of Tulipmania: Money, Honor, and Knowledge in the Dutch Golden Age.