The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

A Different Kind of Beat Poet

Posted on Wed., July 19, 2017 by

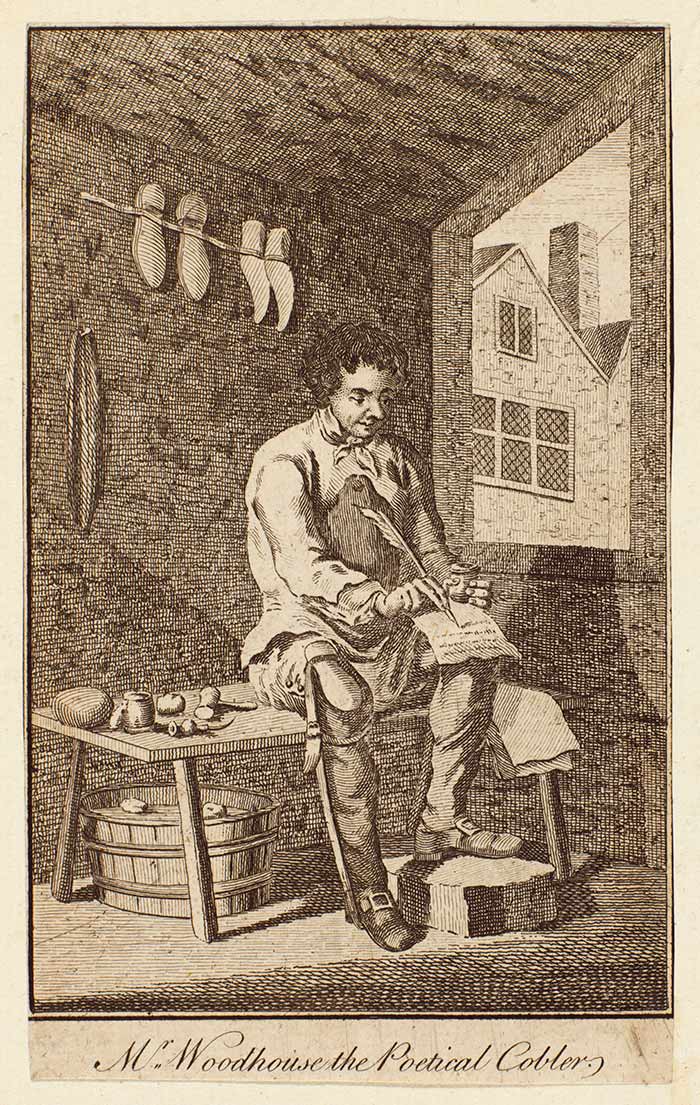

“Mr. Woodhouse the Poetical Cobler,” mounted print in an extra-illustrated copy of James Granger’s Biographical History of England (London, 1769). James Woodhouse (1735–1820), the British poet and shoemaker, did not sit for this popular portrait and hated it, later stating that it “never mark’d his character at all.” He also was annoyed at his characterization as a “cobbler,” a far inferior trade to making shoes. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Most of us have little experience of being thrown out of a garden. When I’ve been found wandering through The Huntington’s orange groves (usually off-limits to visitors), at worst I’m asked by one of the polite staff to ramble somewhere less wild.

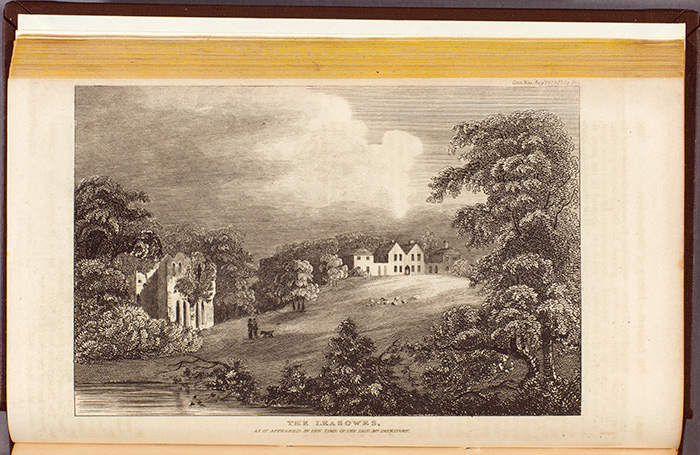

Such was not the case for the British poet James Woodhouse (1735–1820) when, in 1765, he was caught walking in the Leasowes, the famed English landscape garden designed by his friend and mentor William Shenstone (1714–1763). Shenstone had died only two years before, and the new owner—a nouveau riche button-maker with the appropriately Dickensian name of Captain Turnpenny—mistook Woodhouse for a trespasser and furiously attacked him.

My Ph.D. dissertation is on British laboring-class poets—the workers of the past who, against the odds, managed to be published. Woodhouse is an especially interesting example. Scholars suppose that he occupied two separate identities: the submissive, sycophantic poet of the 1760s who sought a leg-up from his patrons; and the radical, rebellious poet of the 1790s whose criticism knew no bounds. Exploring the letters of Woodhouse’s patrons in The Huntington’s collections, I was keen to find out more about the younger poet whom, I felt, might have been misunderstood.

Engraving of the seat of William Shenstone (1714–1763) within the 144-acre Leasowes, as it was before the house was demolished and rebuilt in 1776. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

James Woodhouse lived in the small village of Rowley, in Staffordshire, just two miles away from the Leasowes. The eldest son of a yeoman farmer, he had attended a local free school until he was eight, and a few years later was apprenticed as a shoemaker.

Shoemaking had advantages for someone with a taste for literature. Shoemakers did their work indoors, individually or in small groups, often occupying their minds by singing, sharing news and stories, and in some cases writing poems. As the advertisement to Woodhouse’s first book would later explain, Woodhouse composed verses while working, jotting down the lines between tasks.

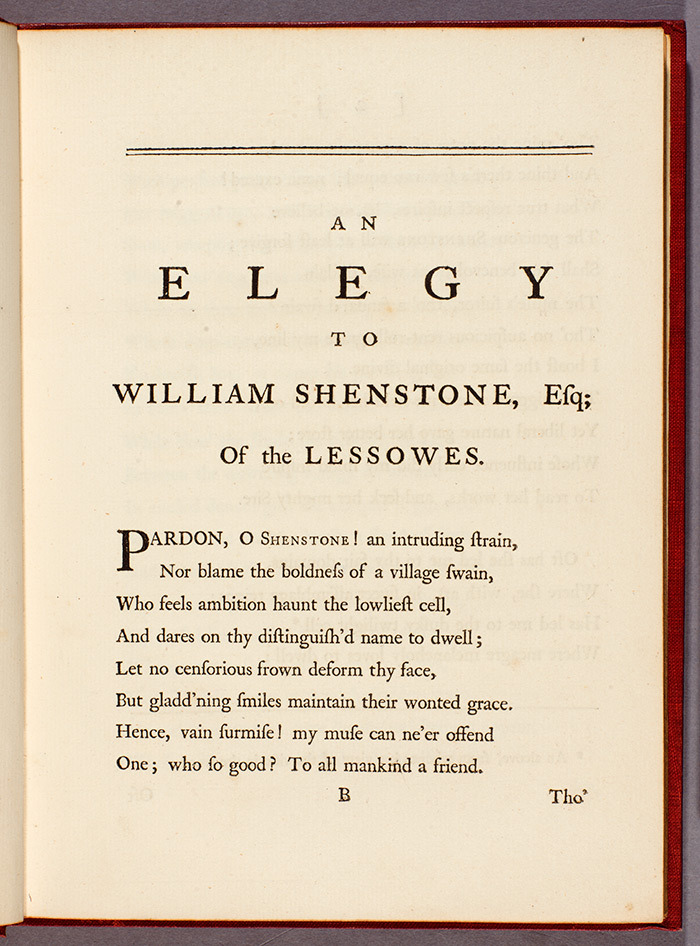

Woodhouse’s penchant for poetry began attracting notice in 1759 when Shenstone closed the Leasowes to the public due to acts of vandalism. In response, Woodhouse wrote an elegy to Shenstone that showed Woodhouse’s keen appreciation of the landscape—with a nod to Shenstone’s genius, of course.

The beginning of Woodhouse’s first elegy to Shenstone in the 1764 Poems. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

A poet himself, Shenstone was impressed. He offered Woodhouse free use of the Leasowes and his library. He invited Woodhouse for dinner and on walks, sent his poems to other literati, and introduced him to his publishers. Shenstone’s influence lasted long after his sudden death in 1763. Woodhouse was crestfallen by this misfortune, writing several poems in memory of him.

Woodhouse’s Poems on Sundry Occasions was published the following year, and he became an instant celebrity. Upon his visit to London, he was fêted by polite society and gained important new patrons, including Lord George Lyttelton, owner of the nearby estate of Hagley, and his friend Elizabeth Montagu, the social reformer and founder of the Blue Stocking Society, a female-led intellectual salon.

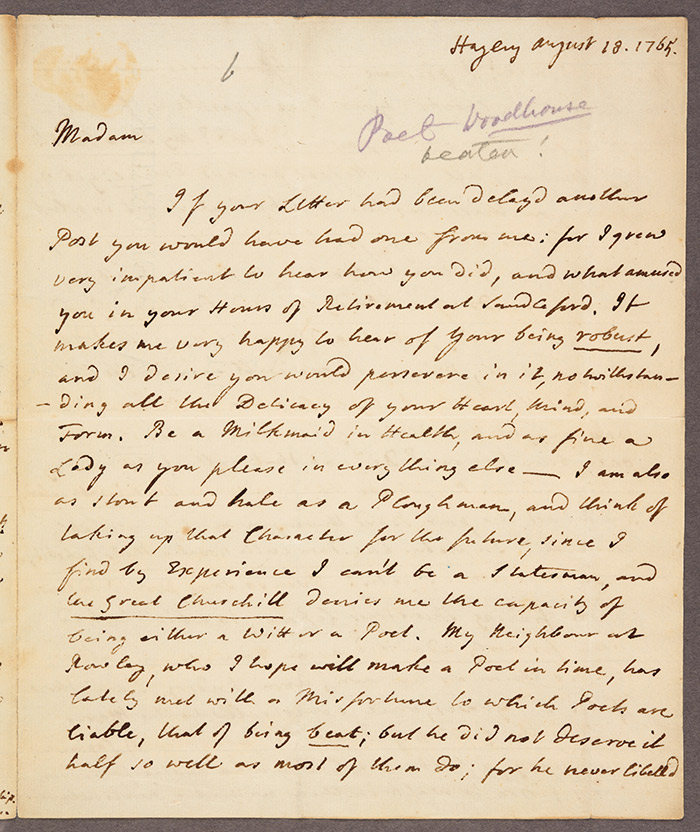

The Huntington’s collection of Elizabeth Montagu’s correspondence—totaling some 7,000 items—includes 14 letters sent to her by Woodhouse. I was also interested in letters between Montagu and her friends, as these mentioned him often. One letter from Lyttelton to Montagu struck me, not least because it had the words “Poet Woodhouse beaten!” scrawled across the top.

The note at the top this letter from George Lyttelton to Elizabeth Montagu was added by one of the early editors of Montagu’s correspondence. Although Lyttelton tried to forge some kind of reconciliation, Woodhouse never forgave Turnpenny for the assault and called him a “fierce Despot” in his 28,000-line poetic autobiography, The Life and Lucubrations of Crispinus Scriblerus, written throughout the 1790s. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The letter describes Woodhouse’s encounter with Turnpenny, shortly after Turnpenny had moved into the Leasowes. Mistaking Woodhouse and his companions for trespassers, Turnpenny went after Woodhouse’s younger brother. Woodhouse stepped in to defend his kin and, things escalating, Turnpenny called for his servants. One heck of a fight must have followed, because Woodhouse, who was six and a half feet tall, went home to his wife with “a bloody Nose, a swelld Face, and a black Eye.”

Lord Lyttelton’s colorful report spans four pages and shows just how much he cared for Woodhouse and was shocked by his mishap. It chronicles the kind of violence that rustics like Woodhouse faced in a transforming British landscape, while revealing Woodhouse’s surprisingly obstinate, even rebellious nature. Lyttelton, for instance, couldn’t understand why Woodhouse didn’t introduce himself to Turnpenny or attempt in any way to make himself known during the encounter.

A plan of the Leasowes showing points of interest, accompanying Joseph Spence’s “The Round of Mr Shenstone’s Paradise.” The fight likely took place on one of the wooded walks visitors were meant to follow. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

This letter is important because it describes just one of many instances in which Woodhouse was confronting the strict social hierarchy of the 18th century. Looking closer, I discovered that Woodhouse had adopted a fake persona to challenge his snooty reception as a “mechanic” poet in newspapers. He also wrote with significant freedom to his patrons, asserting “the natural, tho’ not political, Equality of Mankind.” By seeing the private rebellions behind Woodhouse’s 1760s poetry, I was better able to understand the poetry itself.

Besides a new understanding of Woodhouse, what I took away from my time at The Huntington was a less author-focused approach to epistolary correspondence. While it’s easy to overlook the scandals, stories, and pieces of gossip scattered through letters, once gathered together, these fragments can tell us much about the people of the past.

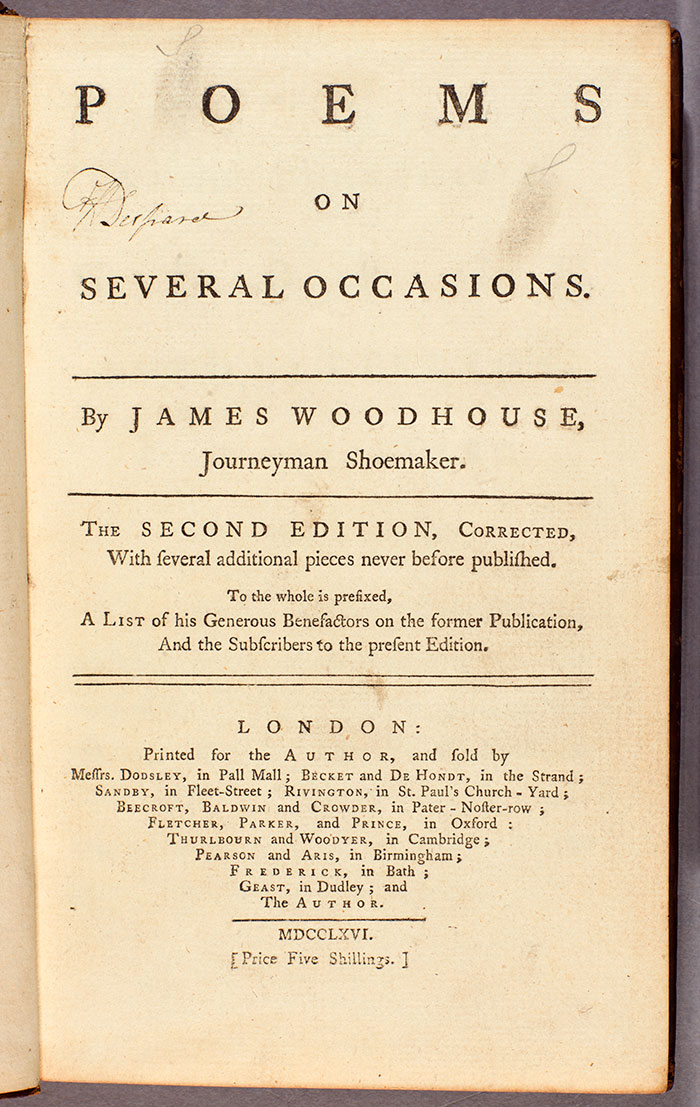

In his 1766 expanded second edition of poems, Woodhouse makes explicit his occupation as a “Journeyman Shoemaker” (not a cobbler) and also writes his own preface. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Adam Bridgen, doctoral student of English at the University of Oxford, is the Leeds Hoban Linacre-Huntington Exchange Fellow for 2017. His full article, “Patronage, Punch-Ups, and Polite Correspondence: The Radical Background of James Woodhouse’s Early Poetry,” is published in the Huntington Library Quarterly.