The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Contested Visions of the Southern California Desert

Posted on Mon., Sept. 25, 2017 by

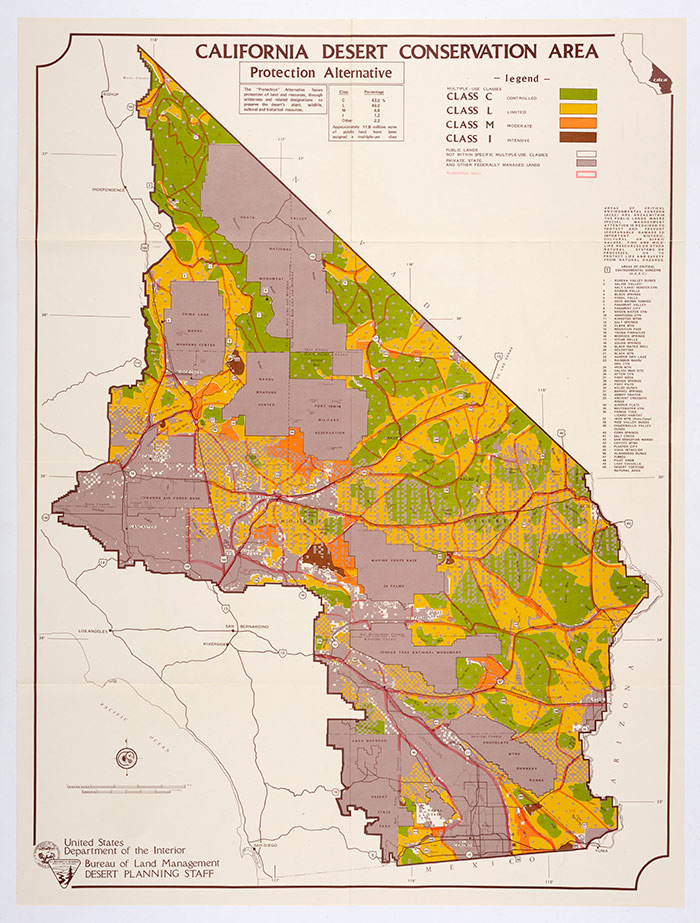

The Protection Alternative in the Bureau of Land Management’s 1980 draft environmental impact statement for the California Desert Conservation Area favors “controlled use” areas—in green—that maximize protection of landscape and wildlife and minimize human impacts. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Just a couple of hours east of Los Angeles is a vast expanse that few Californians know by name: the California Desert Conservation Area, which contains roughly 25 million acres—or one-quarter of the state’s land mass. The region stretches from the Arizona and Nevada state lines to the San Gabriel Mountains and from the Owens Valley to Mexico. It includes such familiar sites as Death Valley and Joshua Tree national parks and the Mojave National Preserve, alongside lesser-known places like the Pinto Mountains and Surprise Canyon wildernesses.

Roughly half of this area comprises federal lands, and in 1976, Congress designated that those lands be managed under a single plan overseen by the Bureau of Land Management. Ever since, the California Desert Conservation Area has been riven with controversy as the Bureau has tried to satisfy the varied interests of energy companies, Native Americans, conservationists, off-road vehicle users, and many thousands more who have visited or lived in the Southern California desert.

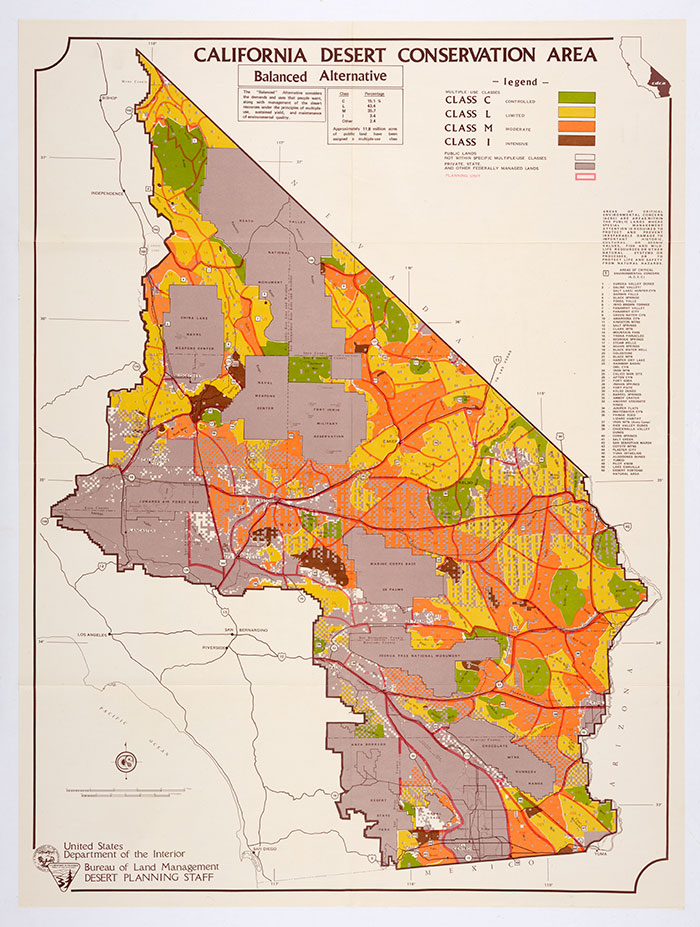

Under the Balanced Alternative, greens recede, making room for yellow and orange “limited use” and “moderate use” areas. In this version, such human activities as motorized recreation and livestock grazing spread through much of the desert. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The story of that ongoing controversy, and of administrative attempts to sort through it, has been recorded in maps, many of which can be found among The Huntington’s Frank Wheat Papers. Wheat (1921–2000) was a California attorney and political activist who, as a Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund volunteer, championed the California Desert Protection Act of 1994 and fought for better protection of the California Desert Conservation Area.

Using maps to render the California Desert Conservation Area in two dimensions was a political act, one that emphasized particular uses or threats with bright colors and stark lines. Maps projected particular sets of values onto a geographical space and suggested what those perspectives might mean for posterity.

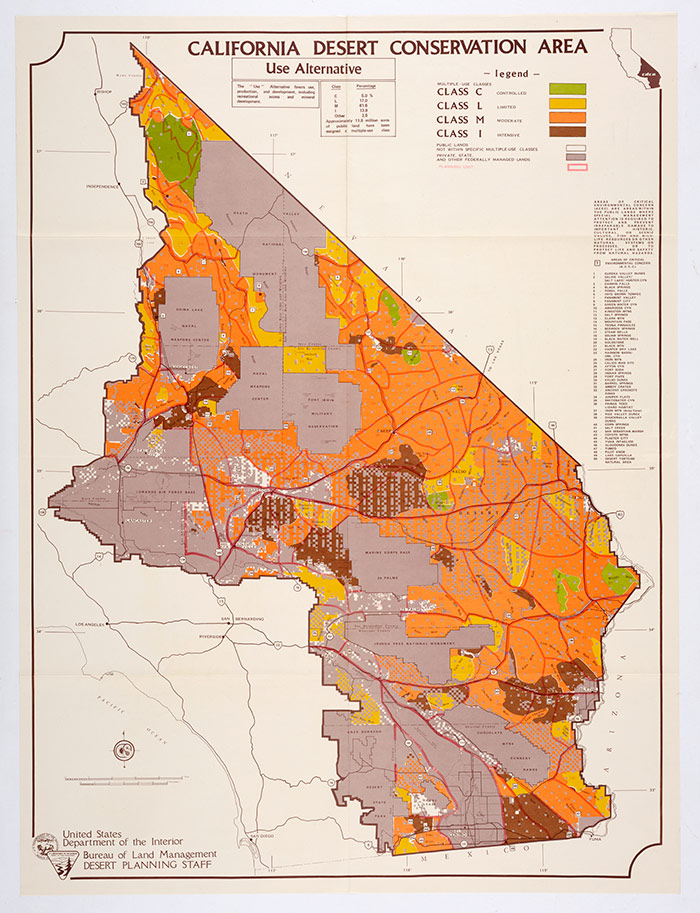

The Use Alternative features only limited green areas and a greater concentration of brown “intensive use” areas, making room for energy facilities and extractive industry. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

During my year at The Huntington, I have been exploring the role that an administrative tool called an environmental impact statement has played in how Americans think about and manage their relationship to nature. Required by law for any “major action” involving a federal agency, these statements document the potential environmental impacts of federal plans and policies and suggest alternative paths. In other words, they try to predict several possible futures.

At times they do this visually, by providing maps that lay out what different futures might look like from above. The Bureau of Land Management’s 1980 draft environmental impact statement for managing the California Desert Conservation Area presents three maps of the region, with green and yellow blocks indicating relatively restricted human use of the land and orange and brown blocks indicating relatively intense use. Three management alternatives—Protection, Balanced, and Use—show a landscape of greens and yellows that give way to oranges and then to browns, as parks and wilderness areas recede and industrial infrastructure spreads in the mapmakers’ imagination.

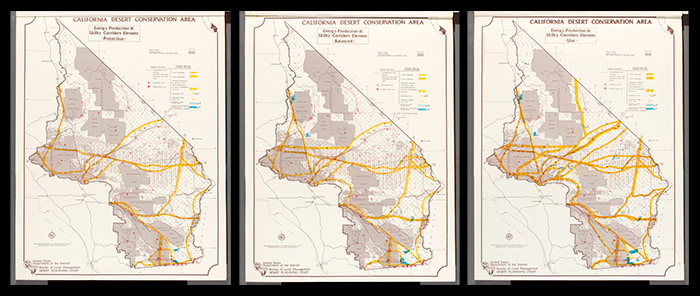

These three maps in the Bureau of Land Management’s 1980 draft environmental impact statement for the California Desert Conservation Area show the consequences of each plan for energy production and transmission. Under the Protection Alternative (left), power plants and utility corridors are few and far between. Under the Balanced Alternative (center), power plants multiply, as does the possibility of such alternative energy sources as wind and geothermal. The Use Alternative (right) conceives of the desert as an important site of energy production and transmission, a source of power for Southern California. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Click here to enlarge image.

Another set of maps in the draft environmental impact statement zero in on energy production and transmission, with scattered power plants and a light network of yellow transmission corridors under Protection and a much heavier presence for both under Use.

Administrative documents offer a relatively tidy presentation of what possible futures might lay in store for a management area. The Frank Wheat Papers also reveal a messier story. Environmental impact statements are public documents and often trigger heated debate. The many interest groups fighting for influence over the California Desert Conservation Area presented their own visions of what could happen to the Southern Californian desert.

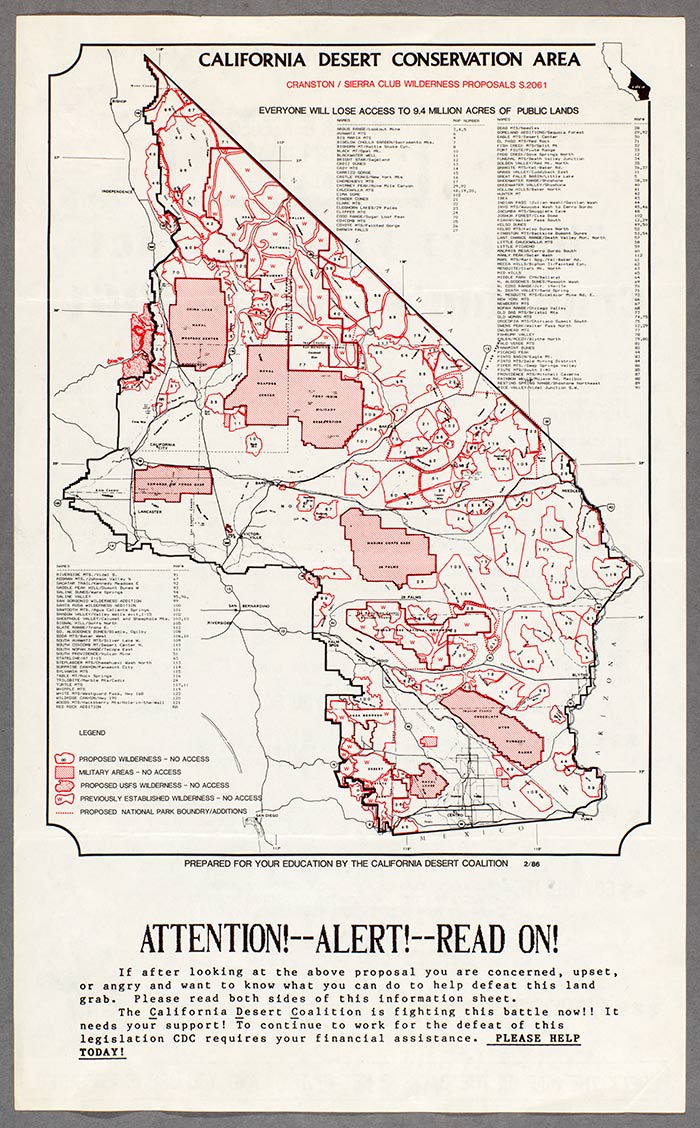

The California Desert Coalition opposed greater restrictions on desert use in the late 1980s. The Coalition's map highlights the number and the extent of potential federal landholdings. By including military installations and already-existing parks and wilderness, the map depicts a desert overwhelmingly under federal control. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The California Desert Coalition—a loose federation of ranchers, public land inholders, and off-road vehicle enthusiasts—published a map in the late 1980s that marked the borders of all federal lands with urgent red lines. By including military properties and already-existing parks and wilderness areas, the Desert Coalition created a view of the future that seemed crowded by federal control, in which dune buggies and property owners would struggle to navigate narrow corridors between heavily restricted zones.

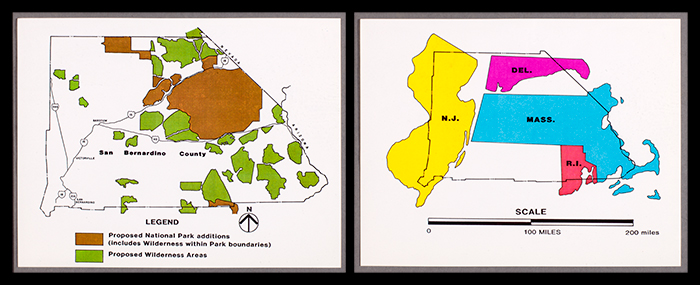

A San Bernardino County supervisor testifying against increased protections for the California Desert Conservation Area in 1989 provided maps with superimpositions designed to show just how vast the areas were that would be ceded to federal agencies.

Testifying in the late 1980s against expanded protection for the California Desert Conservation Area, a San Bernardino County supervisor offered stark illustrations of the relative size of the county and the acreage under consideration within it. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

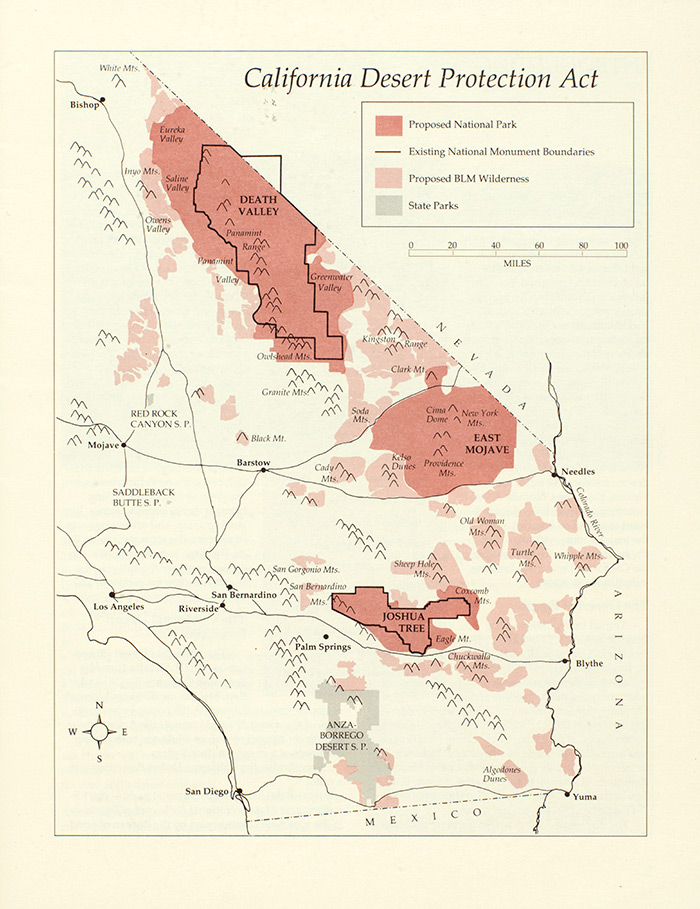

The conservationists of the California Desert Protection League, meanwhile, illustrated their aspirations for protected areas by using muted tones that suggested fluidity. Mountains and highways run in and out of public lands as wildlife and natural resources would. Their map suggests that borders are permeable rather than restrictive, and that different interests can enjoy the desert alongside one another.

Like the arguments attending so many projects and places that involve environmental impact statements, the debate over the Southern California desert comes down to a balanced relationship between human use and conservation. That issue will not be resolved any time soon. The California Desert Conservation Area has inspired—and continues to inspire—contested visions of its future and, by extension, the future of Southern California.

By drawing back to include all of Southern California the California Desert Protection League's map presented a less all-encompassing federal presence, and a sense of balance between major cities and places less dominated by human presence. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Keith Woodhouse is an assistant professor of history at Northwestern University and the 2016–17 Dana and David Dornsife Fellow at The Huntington.