The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

British Theater Censorship in the Georgian Era

Posted on Wed., Jan. 10, 2018 by

Edward Dayes (British, 1763–1804), Drury Lane Theatre, 1795, 15 x 22 in. (38.1 x 55.9 cm.), pen and watercolor. Gilbert Davis Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

I am convening a conference at The Huntington titled “The Censorship of British Theatre, 1737–1843,” which will take place on Jan. 12 and 13 in The Huntington’s Rothenberg Hall. Leading experts on 18th- and 19th-century theater will explore the implications of statutory theater censorship as Britain grappled with issues of modernity, race, gender, and religion during a period of imperial expansion and conflict.

For the literary historian or the student of Georgian culture, the most intriguing consequence of the Stage Licensing Act of 1737 was the establishment of the office of the Examiner of Plays. The Examiner assessed the suitability of new dramatic manuscripts for public performance in patent—that is, royally licensed—theaters. Reporting to the Lord Chamberlain, the Examiner had quite remarkable power to determine what might be consumed by audiences.

John Larpent (1741–1824) is the best known Examiner of Plays. Formerly a clerk at the Foreign Office, he took up the position in 1778 and held it until his death in 1824. Fortunately for us, his wife, Anna Larpent, sold his papers—which included most of the plays submitted to previous Examiners from 1737—and they eventually made their way to The Huntington in 1917.

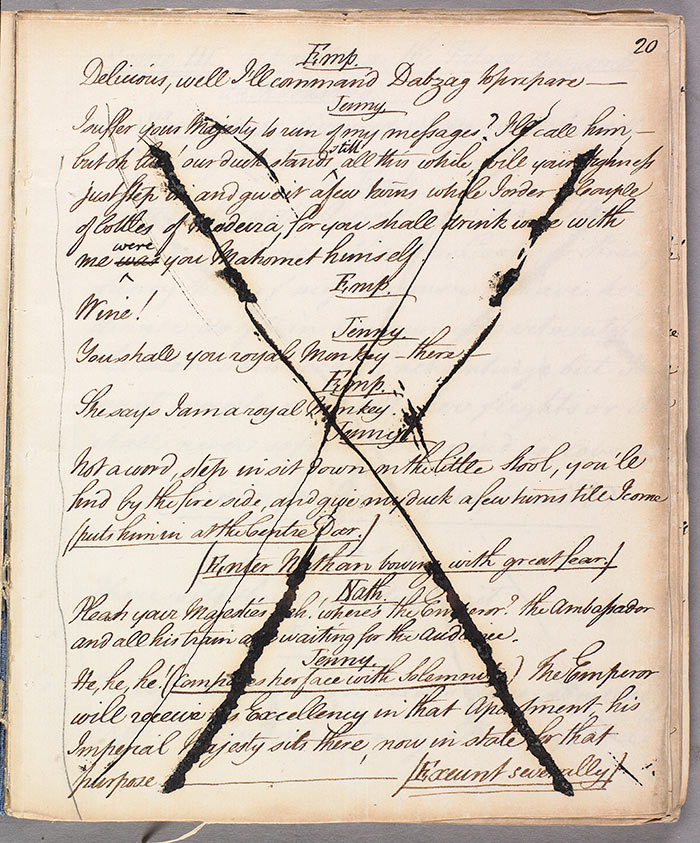

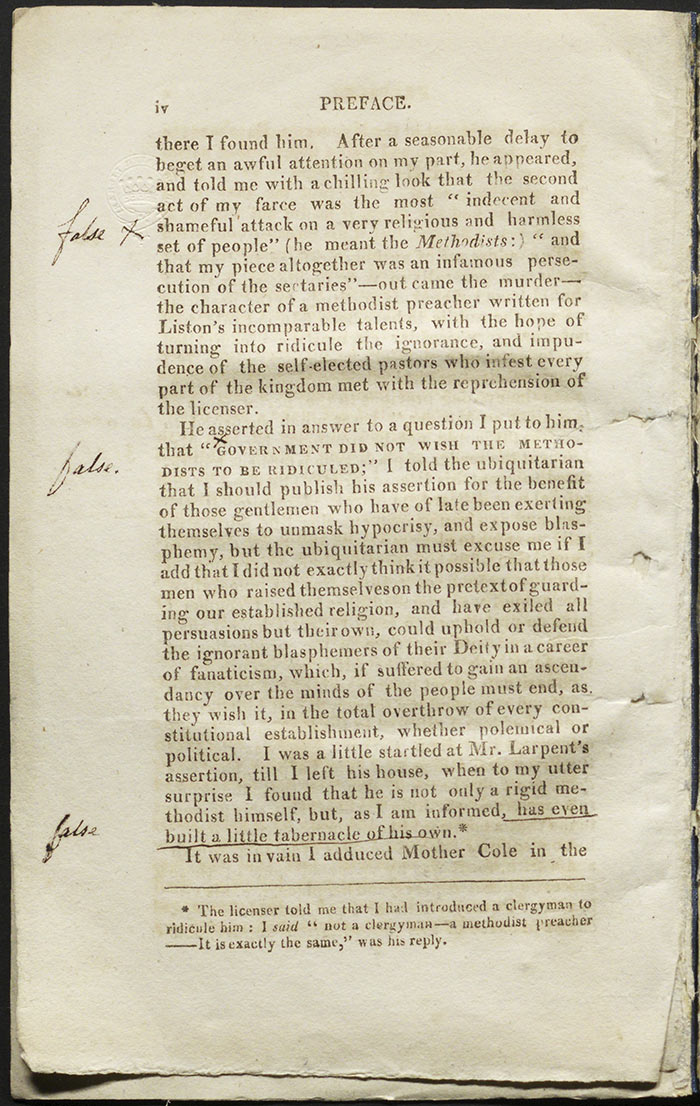

The Larpent Collection comprises more than 2,500 separate manuscript items, many of which contain the various excisions and emendations introduced by the Examiners. While it was rare that a play would be prohibited outright, a significant portion of the collection items have lines or speeches marked “unfit for representation,” “to be omitted,” or are simply scored out, boxed, or marked with an "X." (Our conference will bring the rich archive of the Larpent plays at The Huntington into dialogue with the British Library’s Lord Chamberlain’s Plays, a repository of theater manuscripts after 1824.)

A censored page of John O’Keeffe’s Jenny’s Whim; or, The Roasted Emperor, 1794. Larpent Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The introduction of the Stage Licensing Act in 1737 formalized a censorship regime that had operated on an ad hoc basis since the restoration of King Charles I in 1660 and the subsequent reopening of the theaters. The genesis of the act is complicated and variegated but the repercussions were certainly potent and long lasting: the censorship of the British stage by the state did not cease until 1968.

One might imagine that there would have been widespread opposition to the Stage Licensing Act in 1737, a time when Britain prided itself on the “liberties” its mixed government (where monarchy was tempered by parliament) was believed to facilitate, so different from the “tyranny” of Continental absolute monarchies. But while there was some unease, notably from politician Lord Chesterfield (1694–1793) and writer Samuel Johnson (1709–1784), the general view was that censorship of the theater was a benign way to ensure the morality, stability, and well-being of the nation and its people—an indication of the centrality of theater to Georgian cultural life.

What might raise an Examiner’s hackles? For the most part, censorship was related to political matters. Then, as now, leading political figures became incensed at satirical impersonation. The introduction of the Stage Licensing Act was motivated partly by prime minster Robert Walpole (1676–1745), who became increasingly irked by the mockery he endured at the hands of the novelist and dramatist Henry Fielding (1704–1754) and others. The first play refused a license was Henry Brooke’s Gustavus Vasa (1739), ostensibly a paean to a 16th-century Swedish patriot, but which was really a visceral attack on the perceived self-interest, ambition, and greed of Walpole’s ministry.

Playwrights occasionally protested their outrage at censorship. In this extract from the preface to Killing No Murder (1809), Theodore Hook insists he had no intention of maligning Methodists in his play. The preface is annotated by an equally irate John Larpent, marking up the falsehoods in Hook’s account of their meetings. Larpent Collection. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Political censorship can be traced right through the years 1737 to 1843, particularly at moments of national crisis: the French Revolution provoked a fraught debate on political reform in Britain which increased nervousness about what might be staged in front of “the people.” John O’Keeffe’s Jenny’s Whim; or, The Roasted Emperor (1794) gives us some idea of contemporary sensitivities. Although the play takes aim at the Emperor of Morocco, the rather frenetic marks on the manuscript make it clear that a satirical attack on any dramatic representation of monarchy was not to be tolerated in the wake of the execution of France’s King Louis XVI.

Matters of sex, religion, and economics were also likely to furrow the brow of an Examiner. Suggestions of lewd behavior on the part of the upper classes, mockery of religious figures, or references to harsh levels of taxation were systematically excised from the theatrical repertoire. The Larpent manuscripts provide a remarkably revealing narrative of the sensitivities of British society in the 18th and 19th centuries.

You can read more about the conference program on The Huntington’s website.

David O’Shaughnessy is assistant professor in 18th-century studies at Trinity College Dublin. He is the author of William Godwin and the Theatre and co-editor of The Diary of William Godwin. He is currently editing Ireland, Enlightenment and the English Stage, 1740-1820 for Cambridge University Press.