The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

The Beard Makes the Man

Posted on Tue., Nov. 22, 2016 by

John Deare (British, 1759–1798), Album leaf: Bust of Septimius Severus, Roman Emperor, ca. 1788, pen and black ink and wash on paper, rendered here in black and white. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Is identity mutable? Can you alter who you are? Whether or not real transformation is achievable, it is possible to change how others view you. A new exhibition in the Huntington Art Gallery examines an age-old tool used in the effort to influence perception: facial hair. “A History of Whiskers: Facial Hair and Identity in European and American Art, 1750–1920” includes prints, drawings, and photographs of some impressive and bizarre styles that pushed the limits of follicular fashion.

Nowhere is image more important than in the realm of politics, and this is as true today as it was in antiquity. Beards were part of the political costume of ancient Rome. A drawing by British sculptor John Deare shows Emperor Septimius Severus (A.D. 145–211) with long facial locks—a style known as the “philosopher’s beard” because of the many great thinkers in ancient Greece and Rome who sported it. Portraiture was a vital component of a ruler’s public relations campaign, and the philospher’s beard connoted wisdom. The emperor’s likeness—facial hair and all—appeared on coins, equestrian monuments, and portrait busts, like the one recorded by Deare. Septimius Severus took power at a time of great instability, so it was especially important that he present himself as a thoughtful, level-headed leader. The branding seemed to have worked. He went on to reign for nearly twenty years.

Ehrgott, Forbriger, & Co. (American, 1856–74), A.E. Burnside, Maj. Genl. U.S.A., ca. 1862–69, lithograph. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Grooming manuals of the late 19th and early 20th centuries advised against thin or patchy facial hair, which could make a man appear weak, or so the manuals warned. Ambrose Burnside (1824–1881), Union Army general in the U.S. Civil War, never suffered from scant growth. He cultivated a bold, personal style that earned him a place in the history of facial hair. He is the namesake of sideburns, but Burnside sported more than his eponymous whiskers. The general grew a mustache that extended across his face, covered his cheeks, and connected to his hairline at the ears. This style had already gone out of fashion, however, by the time of Mrs. Humphry’s Etiquette for Every Day, published in 1909. She urged moderation in facial hair, warning that too large a mustache imparts “a belligerent, aggressive air.” Burnside’s style may have been appropriate for leading troops but evidently was ill-suited to civilian life.

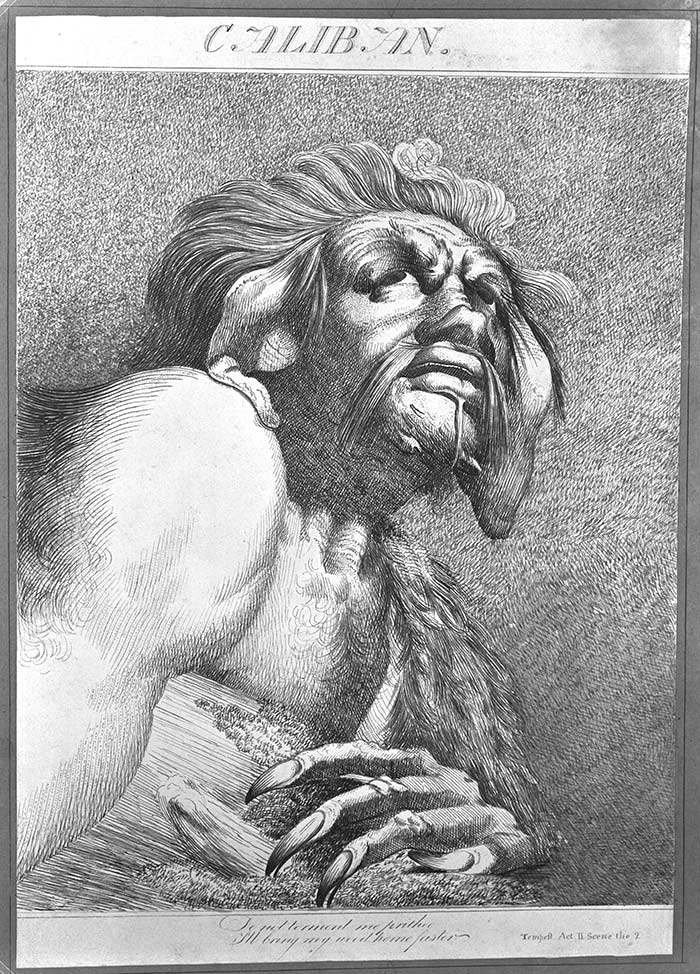

Not all of the images in the exhibition portray historical figures. Take, for example, the image of Caliban by British figure painter John Hamilton Mortimer (1740–1779). Caliban is a beastly character from Shakespeare’s The Tempest, and he is made even more gruesome by means of facial hair. There is no standard way to depict Caliban. His mother is a witch, and Prospero, the play’s protagonist, describes him as a “poisonous slave, got by the devil himself.”

After John Hamilton Mortimer (British, 1740–1779), Caliban, undated, pen and black ink on paper mounted on board, rendered here in black and white. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Some artists imagined him as a deformed man or a creature with a mix of human and fish traits. Mortimer emphasized Caliban’s devilish nature by including a modification of the goatee commonly found in images of Satan, making the beard specifically suited to this hybrid character. Caliban is nefarious, simple-minded, and subhuman. His sagging mustache and pastiche of chin growth are ungroomed and otherworldly, perfectly capturing the character traits of the feral, demonic creature.

One need only look at the preponderance of facial hair on major league baseball players today to realize that beards and mustaches have experienced yet another resurgence. “A History of Whiskers” offers a valuable opportunity to take a look back and observe how men have styled themselves throughout the ages. Fashions have changed, but the desire of individuals to transform how others view them is timeless.

James Fishburne is guest curator of “A History of Whiskers: Facial Hair and Identity in European and American Art, 1750–1920.” He received his Ph.D. in art history from UCLA and is currently a research associate at the Getty Research Institute.