The blog of The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Bad King John

Posted on Fri., Aug. 28, 2015 by

A.A. Milne’s King John stares at a row of Christmas cards he has sent himself in “King John’s Christmas,” from Now We Are Six, first edition, London, 1927. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

We love to hate villains. Harry Potter’s Lord Voldemort horrifies us with his flagrant use of the Unforgivable Curses. Before him, Darth Vader of Star Wars fame was the true embodiment of evil as he built the Death Star and battled his children. But long before the Dark Lord and the Dark Side, there was King John, one of the original bad guys.

With a reputation spanning 800 years, King John may hold the title for the longest-running scoundrel. Most of us first encountered John as Robin Hood’s miserly nemesis. As legend goes, Robin Hood stole from the rich to give to the poor. His heroic generosity was an affront to the selfish Prince John, brother of the righteous King Richard, the Lionheart. Prince John levied crippling taxes on his poor subjects so that he could lounge in luxury. It was Robin Hood’s swift bows and arrows, as well as his skilled swordplay, that ended the tyrannical prince’s scheming.

Robin Hood was a fictional character who stole from the rich to give to the poor. His miserly nemesis, Prince John, was the real thing—becoming King of England in 1199. King John appears in this detail from an illuminated manuscript on vellum of the genealogical chronicle of the Kings of England from the late 15th century. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The youngest of five sons of King Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine, Prince John became King John of England in 1199. During King John’s disastrous reign, Pope Innocent III excommunicated him in a dispute about who should be Archbishop of Canterbury. King John lost key English holdings during a miserable military campaign in France, and after a civil war, his barons forced him to affix his seal to Magna Carta. King John subsequently convinced the Pope to declare Magna Carta null and void, and the country lapsed back into civil war. The war ended only when King John died of dysentery a year later. King John’s bad reputation was well earned, and since his time, no King of England has taken his name.

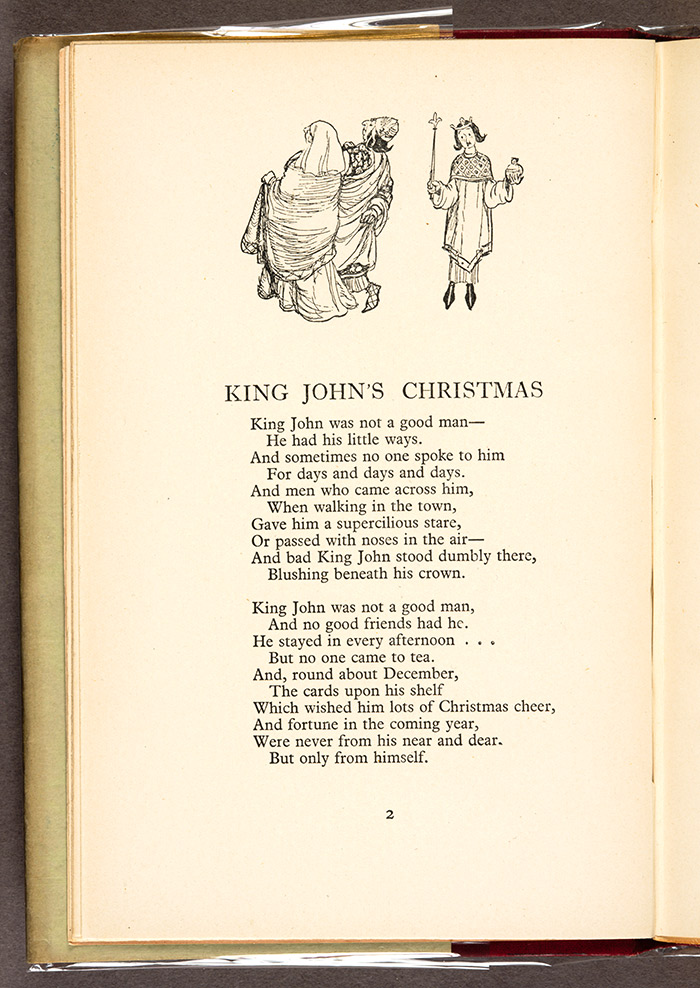

The legend of Robin Hood plays a large role in the perpetuation of Bad King John’s legacy, and over the centuries, many people have had great fun at King John’s expense. In 1927, A.A. Milne (the author of Winnie-the-Pooh) wrote a popular children’s poem titled “King John’s Christmas,” adorned with now-famous illustrations by Ernest H. Shepard. The poem begins:

King John was not a good man—

He had his little ways.

And sometimes no one spoke to him

For days and days and days.

The first page of A.A. Milne’s “King John’s Christmas” as printed in Now We Are Six, first edition, London, 1927. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In Milne’s poem, King John is melancholy about Christmas. What he most wants is a big, red, india-rubber ball, but because he is “not a good man,” no one wants to give him a present. Then, on Christmas morning, someone in a rowdy band of boys and girls throws a big, red, india-rubber ball at King John’s head as he peers out his bedroom window. King John thinks his Christmas wish has finally come true, but we are in on the joke.

The real King John would no doubt have been appalled by his depiction in Milne’s classic poem. But we sit back and relish the moment—watching a legendary bad guy get what he deserves.

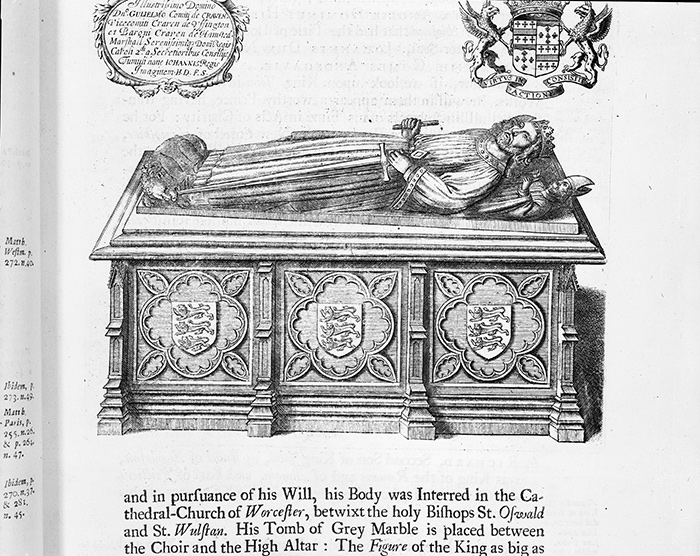

An image of King John’s tomb in Worcester Cathedral in England, from A genealogical history of the kings of England, and monarchs of Great Britain, &c. from the conquest, anno 1066 to the year, 1677, (1707), by Francis Sandford (1630–1694), rendered here in black and white. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

For more about the real-life King John and the history and enduring impact of the Great Charter that King John signed in 1215, stop by the exhibition “Magna Carta: Law and Legend, 1215–2015,” which runs through Oct. 12, 2015, in the Library’s West Hall.

Related content on Verso:

(The) Magna C(h)arta (July 21, 2015)

Running at Runnymede (June 9, 2015)

Vanessa Wilkie is William A. Moffett Curator of British Historical Manuscripts at The Huntington.