The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

The Queerness of Shakespeare’s Sonnets

Posted on Wed., April 4, 2018 by

Shakespeare’s image as it appeared on the title page of Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies, known as the First Folio, published in London in 1623. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

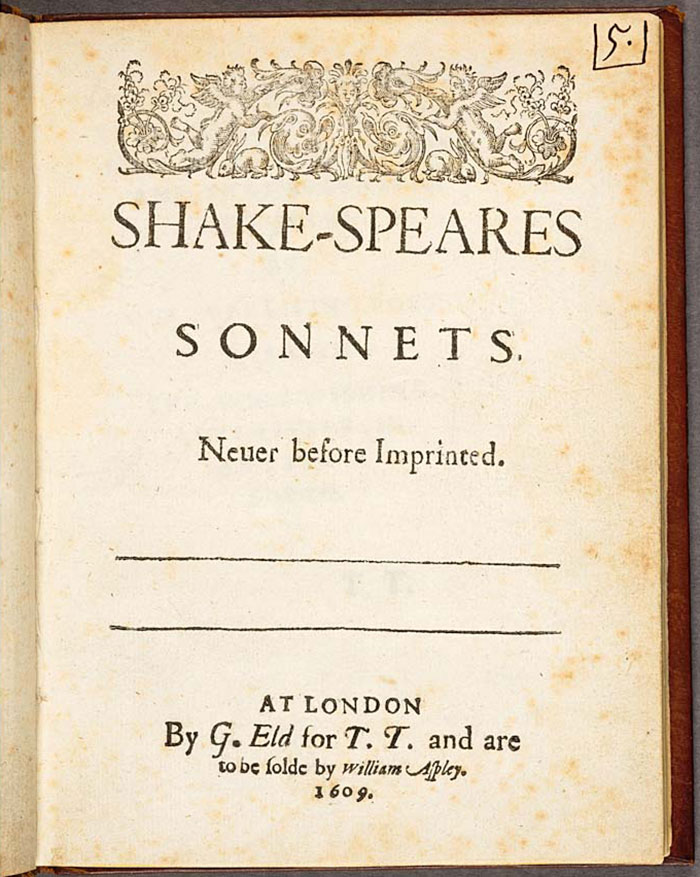

Shakespeare’s Sonnets are enduringly popular. Many people recognize famous lines from the sequence or even know some of the sonnets by heart. Even though the first edition, published in 1609, was not reprinted in Shakespeare’s lifetime, the Sonnets are now among the most culturally valued and widely marketed of his productions. They outsell all of his other works. They are often read at weddings.

Most sonnet sequences of Shakespeare’s time involve a man addressing a woman who is aloof and not interested in his advances. Her refusal is what keeps him writing poems as he tries to persuade her to love him in return. Shakespeare’s Sonnets buck this trend by being addressed to a young man—at least the first 80 percent of them are. This is unusual enough in itself. Still more unusual is the way the Sonnets begin, which is by urging the young man to marry and produce a child. The reason for this, the poet says, is that “From fairest creatures we desire increase” (Sonnet 1). The young man is beautiful, and the poet wants his name and beauty to live forever.

The title page of Shakespeare’s Sonnets , 1609. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

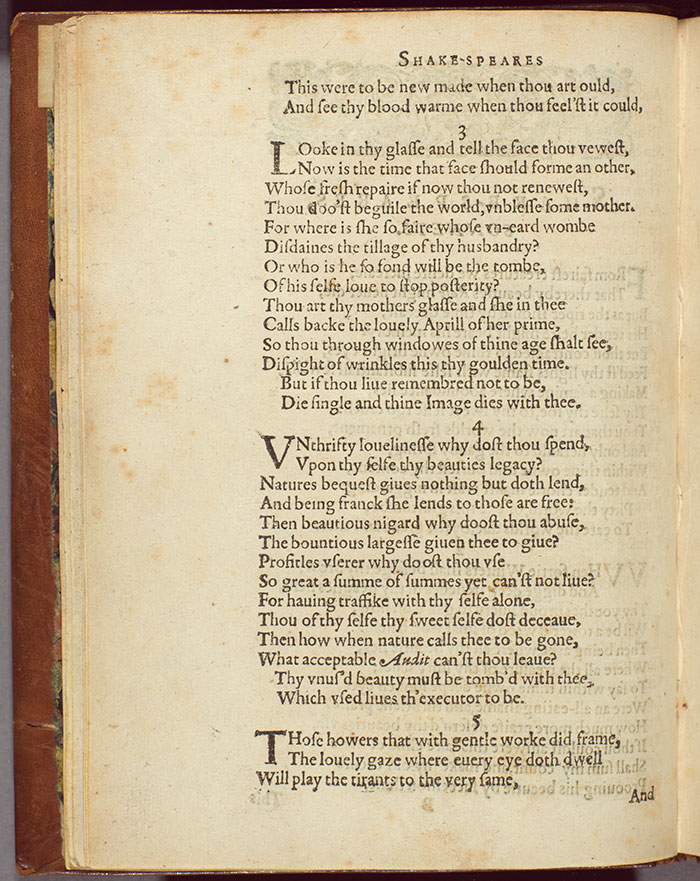

Equally unusual is the way the poet describes this business of making babies, which he compares with the business of making money. Specifically, he compares it with usury, the practice of charging interest on loans. In Sonnet 4, for example, the young man is accused of being a “Profitless usurer.” He is said to be guilty of abusing nature’s gifts by refusing to use them properly: he is not spending what nature lends him in order to make more. “Thy unused beauty must be tombed with thee, / Which usèd lives th’executor to be.” In Sonnet 6, having children is encouragingly presented to the young man in terms of the kind of increase promised by capital investment: “That use is not forbidden usury / Which happies those that pay the willing loan; / That’s for thyself to breed another thee, / Or ten times happier, be it ten for one. / Ten times thyself were happier than thou art, / If ten of thine ten times refigured thee” (Sonnet 6).

This language strikes an odd note because making children might seem a natural process, while making money is an artificial one. For thousands of years, usury had been condemned as unnatural and immoral for just this reason. Money could not breed in the same way that living creatures can. In Shakespeare’s time, this view was beginning to change as lending at interest was becoming more widespread and increasingly acceptable, but there was still a lot of resistance to it. Many people still regarded usury as wrong.

It was this traditional thinking that Shakespeare was challenging when he suggested that having children and practicing usury were basically the same. At a much earlier stage in the history of money, Socrates had described interest metaphorically as human offspring (tokos in Greek). In the Sonnets, Shakespeare effectively turns this metaphor around by describing offspring as interest. He suggests that both are a good thing and an increase in either naturally more so.

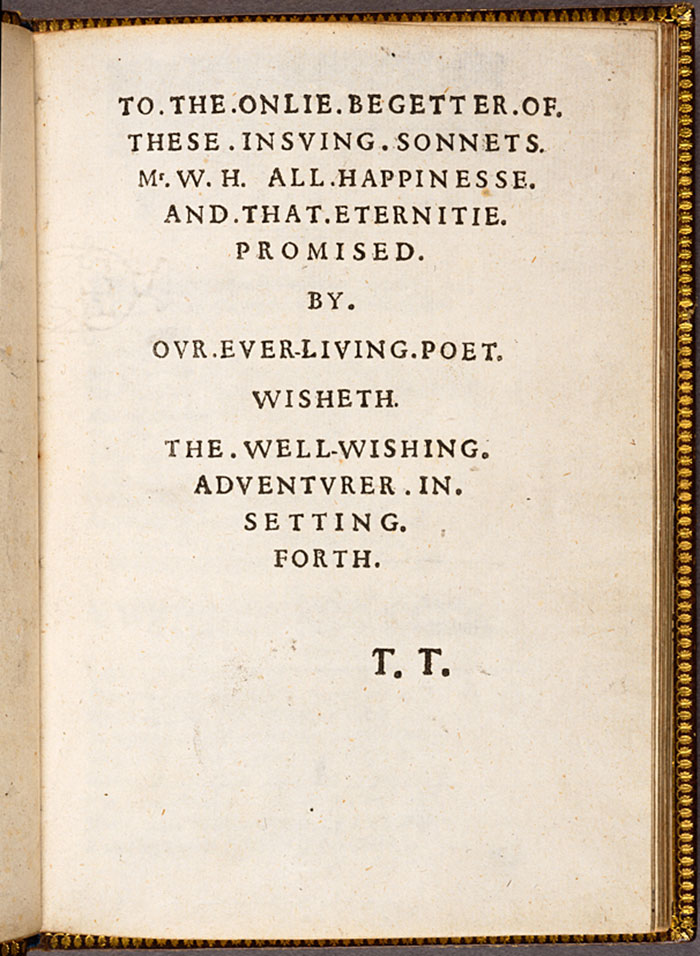

Dedication page of Shakespeare’s Sonnets , 1609. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

One of the things Shakespeare is doing here is encouraging us to think about what is natural and what is unnatural. The young man in the Sonnets is not being asked to sow wild oats, as it were. He is being asked to produce an heir—specifically a son—because this will ensure the continuity of his name down the generations and the proper transfer of property through the male line. However natural it might seem, therefore, the act of producing a child is entirely bound up with such artificial considerations as legitimacy and inheritance. What is “natural”, therefore, turns out to be a very particular way of organizing society that is made to look natural.

This explains Shakespeare’s weird take on the carpe diem motif. Usually, in love poetry, the poet invites the beloved to “seize the day” and make love to him without delay. Shakespeare’s contemporary, Christopher Marlowe (1564–1593), for example, wrote a famous poem on this theme that begins “Come live with me and be my love.” In the Sonnets, however, Shakespeare does not proposition the young man directly in this way. Instead, he asks him to proposition someone else. He tells him there are plenty of women out there who would be happy to bear his child: “. . . where is she so fair whose unear’d womb / Disdains the tillage of thy husbandry?” (Sonnet 3); “. . . many maiden gardens yet unset, / With virtuous wish would bear your living flowers” (Sonnet 16). For all the natural imagery, however, nothing could be less straightforward or direct. It is more a matter of “come live with me and be my love, but first go live with her and be hers.”

By making his beloved a man, Shakespeare is suggesting that we should think twice about what seems “natural” and be a bit less hasty in treating it as something obvious and self-evident. He suggests that appealing to what is “natural” and legitimizing only that is actually appealing to a particular way of organizing society—and here, appealing to a particularly patriarchal and capitalist way, one that tries to pass itself off as “natural,” as just the way things are. We are urged to see that this is, in fact, a fundamentalist position. In describing a love between two men, Shakespeare’s Sonnets challenge the kind of society in which succession (the production of sons) is the only thing that counts as success. Here, the only thing that love begets is poetry—not sons, but sonnets.

Sonnets 3 and 4 in Shakespeare’s Sonnets , 1609. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Looking for more Shakespeare? Come to The Huntington for Shakespeare Day on Saturday, April 7, from 11 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. Performers from LA Opera and the Guild of St. George will perform scenes and songs from some of Shakespeare’s most beloved plays in locations throughout the grounds. General admission.

And, since April is National Poetry Month, why not attend the Claremont Graduate University's 2018 Kingsley & Kate Tufts Poetry Reading and Reception in The Huntington’s Haaga Hall on April 19? Hear Patricia Smith, winner of the 2018 Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award, and Donika Kelly, winner of the 2018 Kate Tufts Discovery Award, read from their work. The reading is free and open to the public. Doors open at 7 p.m.; reading begins at 7:30 p.m. Reception and book sales to follow. Please RSVP via Eventbrite.

Catherine Bates is research professor at the University of Warwick. She specializes in English Renaissance poetry and is currently writing a book on Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Her recent books include On Not Defending Poetry (2017, Oxford University Press), currently nominated for the biennial Society of Renaissance Studies prize in Britain and the MLA James Russell Lowell Prize in the U.S.; and Masculinity and the Hunt (Oxford University Press, 2013), winner of the British Academy Rose Mary Crawshay Prize in 2015.