The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

First Light

Posted on Thu., Nov. 16, 2017 by

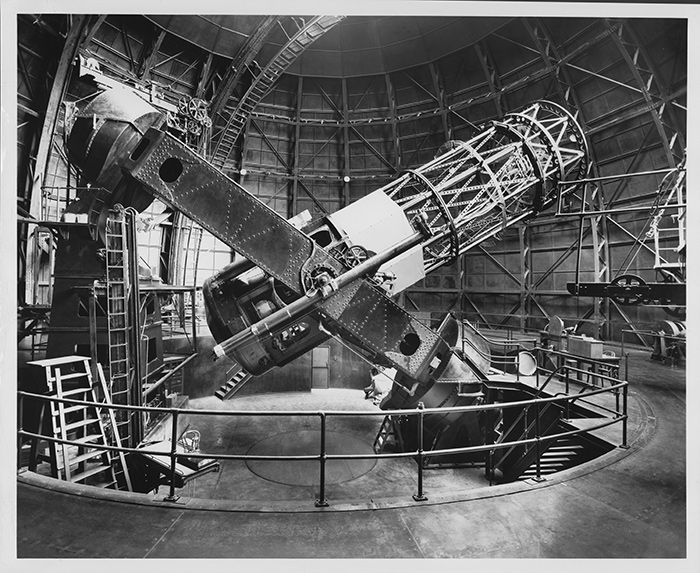

The Hooker 100-inch reflecting telescope, ca. 1940, side view with tube 40 degrees from horizontal. The chair of astronomer Edwin Hubble (1889–1953), on an elevating platform, is visible at left. Photo by Edison Hodge. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In astronomy, the first time a telescope lens is exposed to the night sky for viewing is referred to as first light. Astronomers and the people who design and construct telescopes eagerly await first light, when they can finally see whether the years of planning and testing have produced an instrument that delivers on their expectations.

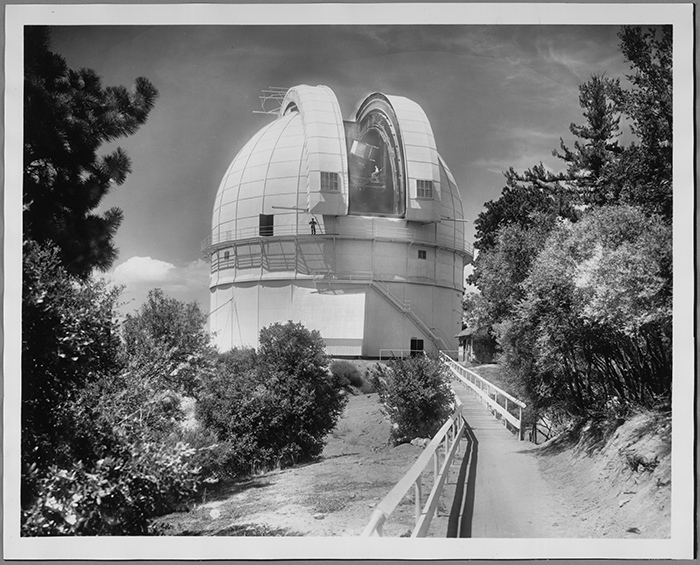

In commemoration of the 100-year anniversary of first light for the massive 100-inch Hooker telescope on Mount Wilson—which was the largest telescope in the world for decades—The Huntington and Carnegie Observatories are sponsoring the annual Dibner History of Science conference, titled “First Light: The Astronomy Century in California, 1917–2017.” The conference takes place in The Huntington’s Rothenberg Hall on Nov. 17 and 18, 2017.

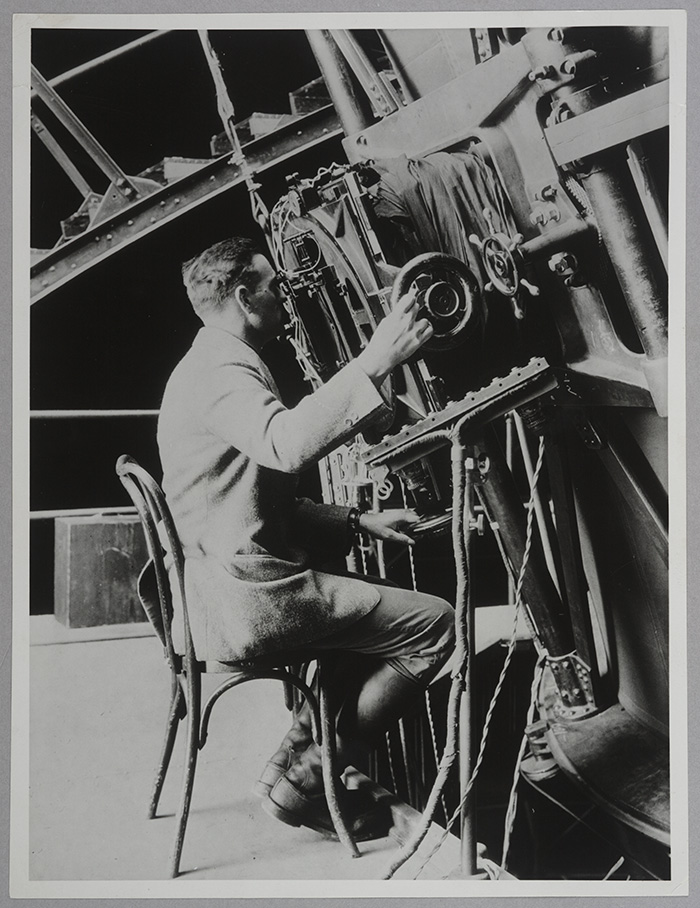

Edwin Hubble (1889–1953), seated at the Hooker 100-inch reflecting telescope, ca. 1924. Unidentified photographer. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The Hooker telescope, which saw first light on November 2, 1917, was responsible for some of the most important astronomical discoveries and observations in history. Most notably, astronomer Edwin Hubble (1889–1953), whose papers are at The Huntington, used the Hooker in the 1920s to discover that what was then known as the Andromeda “spiral nebula” was, in fact, a galaxy outside our own.

I’m co-convening the conference along with John Mulchaey, director of the Carnegie Observatories, the Pasadena-based department of the Carnegie Institution for Science. Carnegie Observatories is home to a multitude of world-class astronomy projects, as well as a vast library of glass-plate photographic images taken at Mount Wilson. The images represent the work of generations of photographers and astronomers and are heavily used by astronomers and historians alike.

At this year’s Dibner conference, we will present a rich view of astronomy through the twin lenses of history and modern science. Each of the conference sessions includes two talks on the same topic, one by a historian and the other by an astronomer.

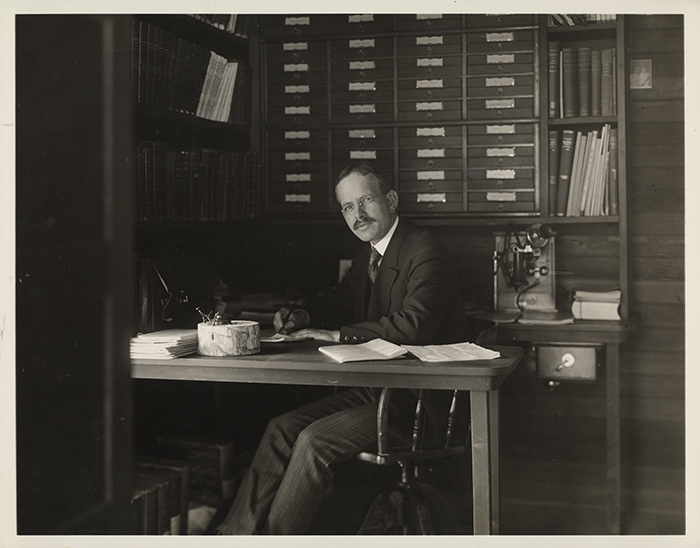

Solar astronomer George Ellery Hale (1868–1938), ca. 1905, seated at his office desk in the Monastery at Mount Wilson Observatory, which he founded. Unidentified photographer. Image courtesy of the Observatories of the Carnegie Institution for Science Collection at The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

For instance, historian David DeVorkin, senior curator at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, will discuss how astronomer George Ellery Hale founded the Mount Wilson Observatory and used it as a test bench for groundbreaking work during the first third of the 20th century. Then astronomer Harold McAlister, the former director of Mount Wilson, will speak about the promise of optical interferometry—a way of combining signals from two or more telescopes to obtain a higher resolution—helping to ensure that the telescopes at Mount Wilson will make significant contributions to a second century of scientific findings.

Another session will feature Barbara Becker, a historian of astronomy at UC Irvine, sharing insights into the relationship between British amateur astronomer William Huggins (1824–1910) and the much younger George Ellery Hale (1868–1938), and their shared passion for solar astronomy. Co-convener John Mulchaey will follow with a talk on current collaborations in the world of astronomy.

Every field of science has a history tracking the inroads (and false starts) that inform its current practice. A careful reading of the history of science provides some of the building blocks to scientific discoveries and technologies. And it offers fascinating stories about the actions and motivations of scientific pioneers and visionaries. We hope you’ll join us.

Observatory dome of the Hooker 100-inch reflecting telescope, ca. 1925, Mount Wilson Observatory. Unidentified photographer. Image courtesy of the Observatories of the Carnegie Institution for Science Collection at The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

You can listen to the conference presentations on SoundCloud.

Daniel Lewis is the Dibner Senior Curator of the History of Science and Technology at The Huntington.