The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Illustrating Poverty and Prisons

Posted on Wed., March 22, 2017 by

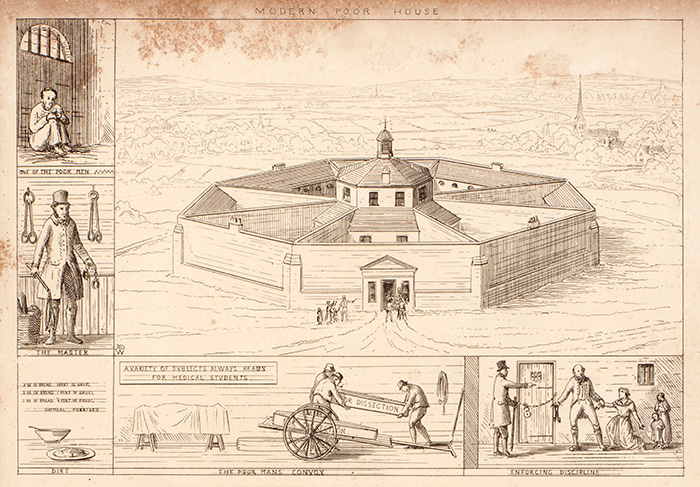

The windowless octagonal Modern Poor House sits isolated on the outskirts of town. Debtors and paupers are whipped and then chained and imprisoned in solitary confinement. Their diet is composed of bread and gruel. Detail from Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin’s “Contrasted Residences for the Poor: Modern Poor House; Ancient Poor House” in Contrasts, or, A parallel between the noble edifices of the Middle Ages, and corresponding buildings of the present day, shewing the present decay of taste, 1841. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

In 19th-century Britain, the mere fact of being poor could land you in prison—debtors’ prison, that is. The history of British prisons and how artists and architects documented the social, political, and legal tensions surrounding prison reform are the main themes of a focused exhibition in the Huntington Art Gallery’s Works on Paper room, on view until June 26.

The exhibition, titled “A.W.N. Pugin, Prisons, and the Plight of the Poor,” includes more than a dozen objects drawn from The Huntington’s Art and Library collections, including drawings, prints, and a rare book by British architect, draftsman, designer, and architectural theorist Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (1812–1852).

Pugin’s architectural manifesto, Contrasted Residences for the Poor, criticized the treatment of the poor and underprivileged following the passing of the New Poor Law by Parliament in 1834. The former Poor Law of 1815 stated that each parish had to look after their own poor, raising funds through taxes on the middle and upper classes. The new law, instituted to reduce rising costs, established workhouses where the poor were required to do manual labor in exchange for food and lodging.

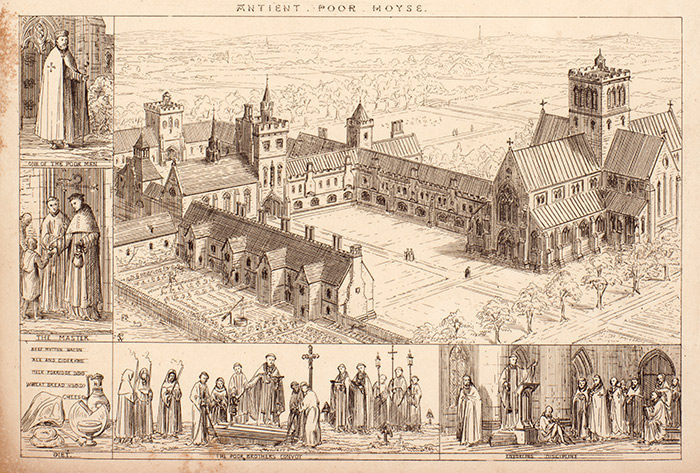

The Ancient Poor House, as depicted by Pugin, was a magnificent almshouse built around a courtyard with an impressive church anchoring the whole complex. Paupers were treated with dignity, receiving clothing and a substantial meal of beef, mutton, bacon, ale and cider, milk and porridge, and bread and cheese. Detail from Pugin’s “Contrasted Residences for the Poor: Modern Poor House; Ancient Poor House.” The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Pugin pointed to the architectural conditions endured by paupers in sordid, industrial city-prisons—where debtors and paupers were fed bread and gruel and often whipped, chained, and imprisoned in solitary confinement—and compared those to an idealized setting where the old English Catholic Church provided hospitality and charity for society’s most underserved. Pugin believed that architecture had the ability to change social environments. For Pugin, English Gothic architecture, with its soaring windows pointed toward Heaven and its foundations firmly grounded in Christian virtues—Faith, Hope, Charity, Fortitude, Justice, Temperance, and Prudence—offered a moralizing architectural fabric that could stabilize and improve what many perceived to be a tortured 19th-century society.

The artworks in this exhibition depict a range of prison styles and highlight the role that these spaces served in containing and punishing criminals, debtors, drunks, gamblers, and paupers. These images helped to document the history of Great Britain’s prison architecture, calling attention to the deplorable treatment of the individuals that they contained.

For instance, Edward Gurden Dalziel’s watercolor Children are the Poor Man’s Riches (inspired by the English proverb) emphasized what many destitute parents faced in the mid-19th century—having to bring their children with them into the workhouses to provide for the family. Dalziel’s tender portrait of a poor but happy family would have clearly contrasted with the appalling conditions that the government provided to the marginalized members of British society.

This watercolor emphasizes what many destitute parents faced in the mid-19th century—having to bring their children with them into the workhouses to provide for the family. Edward Gurden Dalziel (British, 1817–1905), Children are the Poor Man’s Riches, ca. 1855, watercolor, gouache, and pen and ink over traces of graphite on paper, 7 x 5 in. (17.8 x 12.7 cm.). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Similarly, Henry Rushbury’s etching Debtor’s Prison, York shows how the 18th-century prison (constructed 1701–1705) rises above a thick outer fortress wall of an 11th-century castle built by William the Conqueror, providing a towering reminder of the punitive consequences for persons failing to pay their bills.

After this modernized prison was completed, Daniel Defoe (1660–1731), author of Robinson Crusoe, conducted a survey of the public jails in Great Britain and noted that the York debtors’ prison was “the most stately and complete of any in the kingdom, if not in Europe.” The different floors of the prison were used to segregate the different types of offenders—debtors above and felons below. Though “stately” in its exterior appearance, inmates were often crammed 15 to a filthy cell. The combination of overcrowding and lack of hygiene in prisons led to massive outbreaks of “jail fever,” probably typhus, which resulted in tragic loss of life.

Together, the drawings, prints, and illustrated books in this exhibition reveal the role that representations of British prison architecture played as both a framing device and a backdrop for discussing and visualizing the politically and morally charged debates about 19th-century prison reform.

This etching shows the 18th-century debtors’ prison in York rising above a thick outer fortress wall of an 11th-century castle built by William the Conqueror, providing a towering reminder of the punitive consequences for persons failing to pay their bills. Henry Rushbury (British, 1889-1968), Debtor’s Prison, York, 1933, etching and drypoint on paper, 10 3/4 x 14 9/16 in. Gift of Russel I. Kully. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Courtney Skipton Long is guest curator for “A.W.N. Pugin, Prisons, and the Plight of the Poor.” She received her Ph.D. in the history of art and architecture from the University of Pittsburgh in 2016 and is currently the Zvi Grunberg Postdoctoral Fellow at the Bruce Museum in Greenwich, Connecticut.