The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

Getting to Know Jane Austen Better

Posted on Tue., June 16, 2015 by

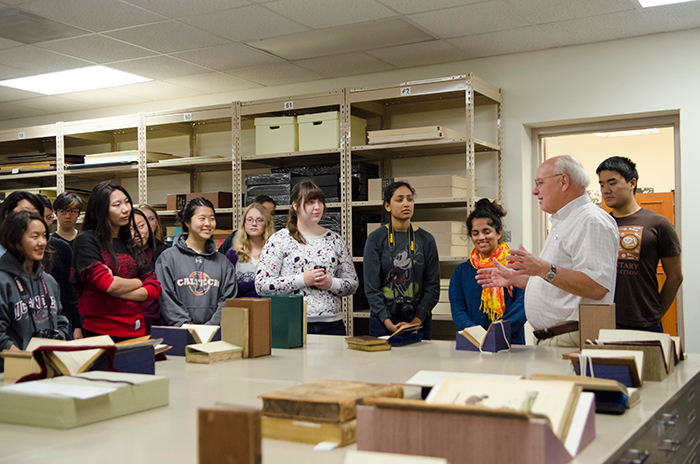

During a visit to The Huntington, Caltech professor Kevin Gilmartin shows his English 127 students a book illustrating “monstrosities of fashion.” Photo by Kate Lain.

Few people can make literature jump off the page like Kevin Gilmartin. Professor of English and 2015 recipient of the Richard Feynman Prize for Excellence in Teaching at Caltech, he has taught at The Huntington’s neighbor institution for 24 years. When he brought a class studying the novels of Jane Austen to the Huntington Library in May, the reasons for the Feynman honor were clear: learning from Professor Gilmartin is like chatting with a good friend brimming with fresh news.

“I enjoy introducing my students to the fascinating print record from the period that Austen’s novels inhabit, including manuals of conduct for young women and instructional pamphlets on dancing and gardening that they can view online,” says Gilmartin. “It’s a way to get them thinking about history in fiction and through fiction, but then too considering it in material terms. Visiting The Huntington then gives my students the opportunity to see such items close up, not just in digital form.”

A hallmark of Gilmartin’s teaching is helping students understand the historical context in which literature is produced. Collaborating with Alan Jutzi, The Huntington’s Avery Chief Curator of Rare Books, helps Gilmartin illuminate the author’s wider world, and the two have worked together in this way for over a decade.

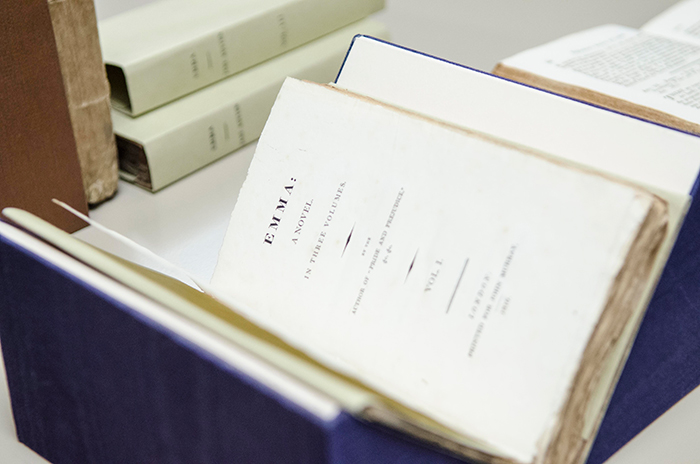

A first edition of the first volume of Jane Austen’s novel Emma, 1816, with board covers, untrimmed. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Photo by Lance Hayashida/Caltech.

In preparation for the Austen class visit, Jutzi and his team retrieved archive treasures and arrayed them atop cabinets so that students could circle them, observing and pondering. The display would make any 21st-century Austen fan swoon with pleasure. And Gilmartin acknowledges that he learns something new on these occasions—this time, for example, about the extraordinary range of The Huntington’s collection of 18th-century visiting cards, and its rare admission ticket to Almack’s, a London social club that was among the first to admit men and women.

Gilmartin and Jutzi tag-teamed throughout the visit on a running commentary, starting with a look at Austen first editions that were originally purchased by Henry Huntington. The novel Emma, for example, came from the publisher in three volumes with board covers, untrimmed, to allow them to be taken apart and bound in leather, according to the wishes and resources of the buyer. Jane Austen’s name does not appear on any of the title pages, although the come-on “From the Author of ______” (fill in the title of Austen’s most recent hit) is prominent. Only in the posthumous double volume of her first and last books—Northanger Abbey (never published in her lifetime) and Persuasion—is she mentioned as the author in the introductions.

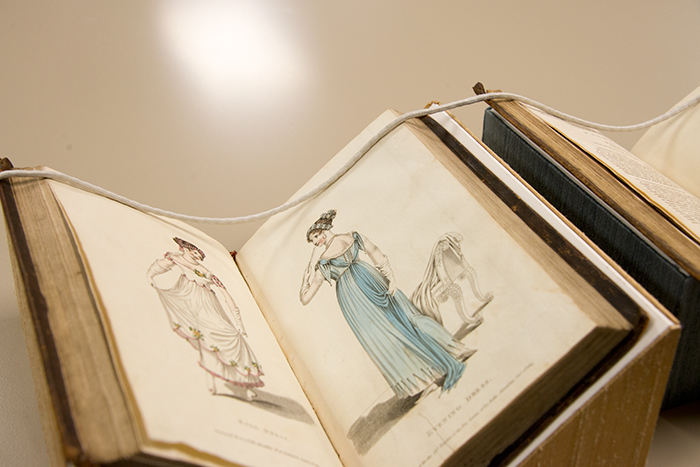

The Mirror of the Graces or The English Lady’s Costume by a Lady of Distinction, 1813. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Photo by Kate Lain.

Unhappy with her first publisher, Austen trusted her naval brother to negotiate the publication of her later novels. Gilmartin pointed out that Austen eventually saw the Royal Navy as a new professional class superior to the gentry. Her esteem for navy men is evident in her last novel, Persuasion, and particularly in her depiction of Captain Frederick Wentworth, who is noble in every way—except by birth.

The pages of the hand-colored volumes presented by Jutzi speak to the class distinctions and social rituals of Austen’s time. Two books—among the most popular on the students’ circuit—reveal the pecking order of landscape gardening.

One is a book for tourists illustrating the gardens of great houses, such as the grounds at Pemberley, Mr. Darcy’s estate in Pride and Prejudice, where the novel’s heroine, Elizabeth Bennet, pays a visit with her aunt and uncle. Her satisfaction suggests that the estate is perfect as it is.

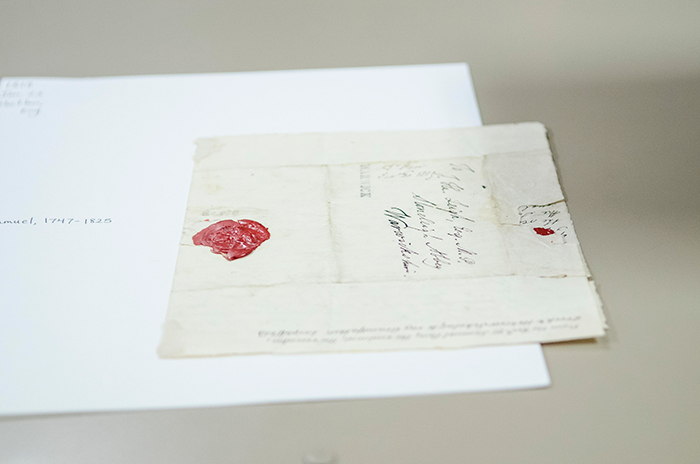

A letter from the Leigh Family Papers, unpublished letters and manuscripts from Jane Austen's mother's family, 1686–1823, 1866. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Photo by Lance Hayashida/Caltech.

By contrast, Mr. Rushworth, the somewhat clueless landowner who enters into a disastrous marriage in Mansfield Park, talks of hiring the fashionable landscape designer Sir Humphry Repton. From Repton, he would have received a Red Book, customized for his estate, using fold-back inserts to show before and after views of the grounds; Rushworth, however, would have had to make the improvements to his land on his own.

Ladies in Austen’s time suffered no shortage of printed guidance. The Mirror of the Graces or The English Lady’s Costume lay open for Gilmartin’s students to view illustrations of fashionable “Morning Dress” and “Evening Half Dress.” The Lady’s Elegant Jester, another item on display, provided jokes for polite society.

Jutzi pointed out that the British are second to none at skewering. In the illustration “Vis a Vis Accidents in Quadrille Dancing,” a gentleman takes a header on the dance floor, contrary to what we’ve come to expect from BBC productions of Austen’s novels, in which the dancing highlights precise patterns and elegant moves.

Alan Jutzi, The Huntington’s Avery Chief Curator of Rare Books, has been collaborating with Caltech’s Kevin Gilmartin for more than a decade to help students understand the historical context in which literature is produced. Photo by Lance Hayashida/Caltech.

Some students spent quite a bit of time with the letters of Austen’s mother’s family, the Leighs, manuscripts acquired by The Huntington in January 2015. (Austen’s own letters were burned per her request.) The wording, the handwriting, and the folding of the letters are all touchstones of her day.

How do Caltech students respond to such visits? “I regularly get what seems to me like Alan Jutzi fan mail in my course evaluations for classes that have visited The Huntington,” Gilmartin reports. And some Caltech students become so enthusiastic about Gilmartin’s teaching that they wind up double majoring in English. The Gilmartin-Jutzi collaboration serves as a wonderful example of how a phenomenal teacher and a beloved curator can bring the past to life for a new generation through an engagement with The Huntington’s collections. Such a match surely would have made Jane Austen smile.

On our Tumblr, you can find an animated GIF of before and after views in Sir Humphry Repton’s Sketches and hints on landscape gardening, London, 1794.

The Leigh Family Papers—unpublished letters and manuscripts from Jane Austen's mother's family—have been fully digitized and may be viewed at the Huntington Digital Library.

Linda Chiavaroli is a volunteer in the office of communications at The Huntington. She is a Los Angeles-based communications consultant.