The Huntington’s blog takes you behind the scenes for a scholarly view of the collections.

EXHIBITIONS | Extending the Field of Photography

Posted on Fri., Jan. 11, 2013 by

The website for “A Strange and Fearful Interest” will remain online after the close of the exhibition.

You have just a few more days to see the exhibition “A Strange and Fearful Interest: Death, Mourning, and Memory in the American Civil War.” Although it finishes its run on Monday, Jan. 14, you will be able to continue to explore the companion website, which allows you to take a closer look at more than 50 images; listen to accompanying commentary by scholars and an original sound work by artist Steve Roden ; and view a short film showing Barret Oliver practicing the art of 19th-century photography.

The show was curated by Jennifer A. Watts, curator of photographs at The Huntington. Her title was inspired by remarks made by Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. (1809–1894) after he saw photographs from the Battle of Antietam: “The field of photography is extending itself to embrace subjects of strange and sometimes of fearful interest.”

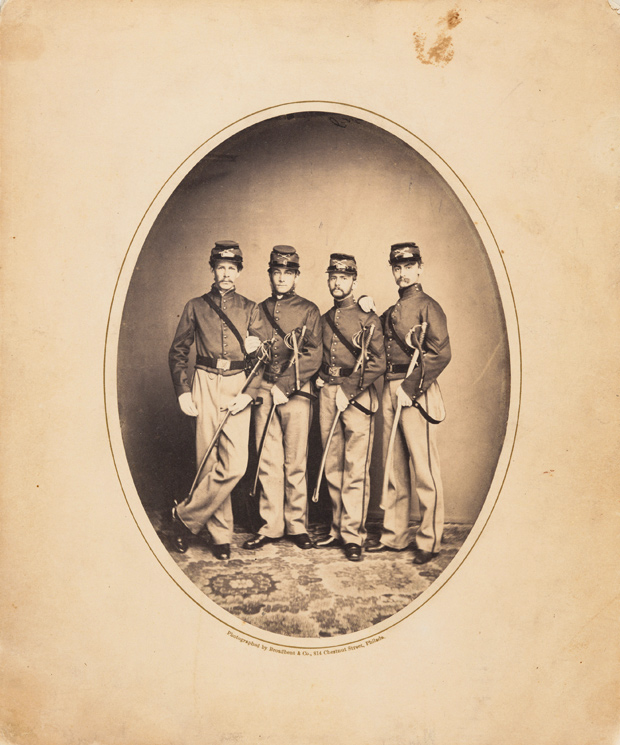

Corporals of the First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry, 1861. Albumen print; 8 1/4 x 6 in. Broadbent & Co. (active 1858–1863). Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Watts explains that the so-called field of photography was still quite new when war broke out between the North and the South, as soldiers and their loved ones carried photographs of one another in pockets or bound in tiny albums. The intimacy of the medium extends to battle scenes reproduced as stereographs or cartes-de-visite. Visitors to the exhibition are invited to view such images with magnifying glasses or stereoscopes. The website builds on this experience—the high resolution of the photos online allows viewers to isolate details and magnify them many times over.

Watts indicates that the fascination with Civil War photographs did not endure after the end of the war. Many photographers went bankrupt, including famed photographer Mathew Brady. He died penniless in 1896, just as the first waves of commemorations showed how there might be a revival of interest in such horrible imagery. One of the sections on the exhibition website is devoted to commemorations, including group reunion portraits of Confederate and Union soldiers at the end of the 19th century.

“A Strange and Fearful Interest” coincides with yet another period of commemoration as we continue to mark the 150th anniversaries of the Civil War’s major milestones. Each generation has had to grapple with it anew, says Watts, who has used the website to expand on the interpretive framework she executed in the galleries.

Wheatfield in Which General Reynolds Was Shot, July 1863. Albumen print; 6 x 8 ⅜ in. Attributed to Egbert G. Fowx (born ca. 1821). The famous Civil War photographer Mathew Brady is the man standing at the fence. Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

A set of scholarly commentaries—available only on the website—supplement the labels from the gallery. Scholars included in the audio component are David W. Blight, author of Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory and American Oracle: The Civil War in the Civil Rights Era; William Deverell, director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West and currently at work on a book about the redemptive West in post–Civil War America; Alice Fahs, author of The Imagined Civil War: Popular Literature of the North and South, 1861–1865; Richard Wightman Fox, who is working on a book on Abraham Lincoln’s funeral; Gary W. Gallagher, author of The Confederate War and The Union War; Harold Holzer, author of many books on Lincoln, including Lincoln: How Abraham Lincoln Ended Slavery in America; James M. McPherson, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era; and Joan Waugh, author of U. S. Grant: American Hero, American Myth.

Watts also wanted to include the perspectives of contemporary artists in her re-envisioning. Sound artist Steve Roden created an original sound installation, “completely silenced”; you can listen to a 3-minute clip on the website. “In the Usual Manner” is a short film featuring contemporary artist Barret Oliver, who creates new work by using the tools of 19th-century photography. Just this week the film was awarded a Jurors’ Citation at the 2013 Black Maria Film Festival, in Jersey City, N.J.

Reunion of Confederate and Union Commanders and Veterans at East Cemetery Hill, Gettysburg, April 29, 1893. Albumen print; 9 x 15 in. William H. Tipton (1850–1929). Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

“What I really hoped would come out of the movie with Barret was to give people a sense of the poetry of making photography,” said Watts. “It’s a very thoughtful process; it’s something that demands a lot of time and attention, you have to think very carefully and consciously about what you’re going to be taking, what image you’re going to make.”

After 150 years, there are still many ways to look at the Civil War. Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. also recognized the power the war might have on subsequent generations. “War, when you’re at it,” he wrote, “is horrible and dull, but with the passage of time it becomes divine.” Divinity might be too much to ask even after all this time, but the passage of time will likely continue to bring fresh perspectives from curators, scholars, artists, and anyone who manages to see the photos in person, in books, or online.

Matt Stevens is editor of Verso and Huntington Frontiers magazine.