Mysterious Manuscript in a Silk Purse

Posted on Wed., Oct. 21, 2015 by

An intimate glimpse at a Medieval poem put to a surprising use

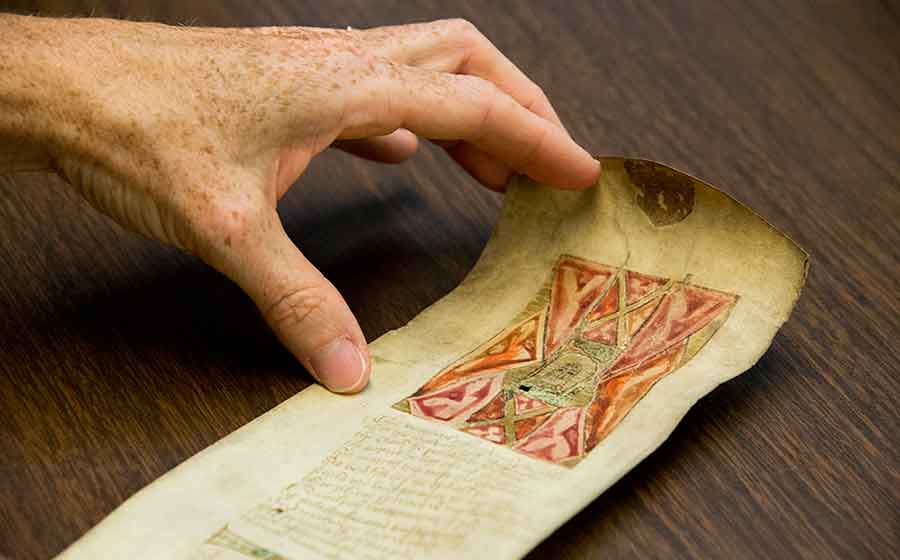

The Huntington Library's manuscript of a 15th-century English poem written on a scroll of parchment approximately four inches wide and five feet long. The illustration and opening lines of the poem depict the Christological artifact known as Veronica's veil. Christ's face is just visible in the center of the image. Photograph by Kate Lain.

As a graduate student doing research in the library at The Huntington in the summer of 2002, I examined a manuscript that surprised me so much that it would take me more than 10 years to fully articulate my response. At the time, I was writing a doctoral dissertation on the symbolic nature of clothing in medieval English poetry, and I knew that this particular manuscript recorded a unique Middle English poem I had recently begun to study. I asked to see it, along with a series of other rare manuscripts, because I knew from its catalogue description that it had illustrations to accompany the poem, which was about various sacred objects associated with Christ's life and death. That manuscript ended up being a tiny roll identified by the call number HM 26054. When I went to pick it up from the librarian at the call desk in the reading room, it arrived in an emerald green silk bag with golden drawstrings, the whole thing not much larger than the palm of my hand.

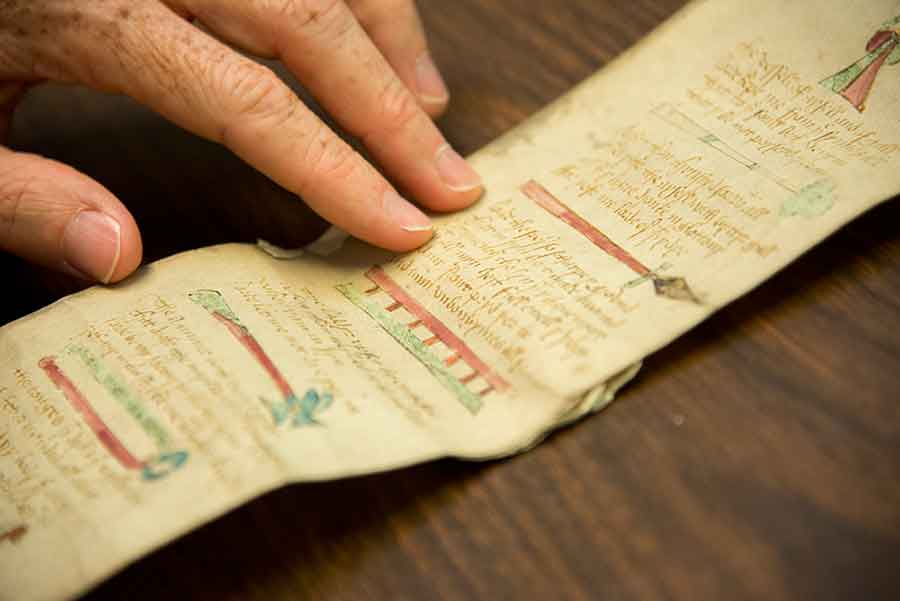

In the Middle Ages, the tiny roll was most likely carried in a leather pouch. For several decades, however, it has been kept in this Victorian silk purse with golden drawstrings. Photograph by Kate Lain.

I should admit that in this early period of my archival research, I didn't always have a full grasp of the size or shape of the manuscript I had called up to examine, and I was often surprised by the material presence of an item as I brought it back to my desk for closer study. But this object was even more startling than usual; the delicate 19th-century silk bag implied that the mysterious manuscript inside was to be treated like a precious piece of jewelry. More used to carrying heavy, slightly bulky, brown leather books back to my research station, I felt this time like I was carrying an intimate possession—a lady's reticule with unknown personal items inside.

That day in the library, as I somewhat self-consciously opened the silk bag and unrolled the narrow but unexpectedly long manuscript (roughly four inches wide and five feet long), I became painfully aware of the vast and often obscuring difference between reading a medieval poem in a modern edition and reading it in its original format. While my initial interest in the poem written in this manuscript was its curious fixation with the material objects of Christ's Passion, I had until that moment been blind to just how curious the poem's own material circumstances were. Why was this manuscript so narrow and long? Why was it in roll format at all, a form used primarily for administrative court documents and royal genealogies? Why were its 24 illustrations, while charming in their simplicity, so crudely drawn?

The manuscript is illustrated with objects related to the Crucifixion and its aftermath, as narrated by the gospels of the New Testament (from right to left): the lance that the soldier Longinus used to pierce Christ's side, creating his fifth wound; the ladder needed to take Christ's body down from the cross; and the hammer and tongs used to remove the nails from Christ's hands and feet. Photograph by Kate Lain.

All worthy questions, but unfortunately not related to the topic of my dissertation. Most of the analysis I originally wrote on this poem was dropped from the final draft of my doctoral work, and what I did manage to keep in that document was eventually cut from my first monograph. But I always planned to return to the arma Christi manuscript—I was on intimate terms with it now, and its mystery would not let me go.

CURIOUS OBJECT ABOUT CURIOUS OBJECTS

The so-called arma Christi poem—a Latin phrase meaning the "arms" or "instruments" of Christ--—was written in Middle English in the 15th century and survives in 20 manuscripts, two of which are housed at the Huntington Library (HM 26054 and HM 142). This fascinating poem is simultaneously a prayer, an ode, and a visual study of the many material objects associated with Christ's Passion. Some of these objects presented in the poem are clearly miraculous, such as Veronica's veil and the famously "seamless" garment worn by Christ, but most, such as the pillar, ropes, and blindfold used in Christ's mocking, and the ladder, hammer, and nails used during and after the crucifixion, are more mundane—a cluster of otherwise unremarkable things made spectacular by their role in this singular event.

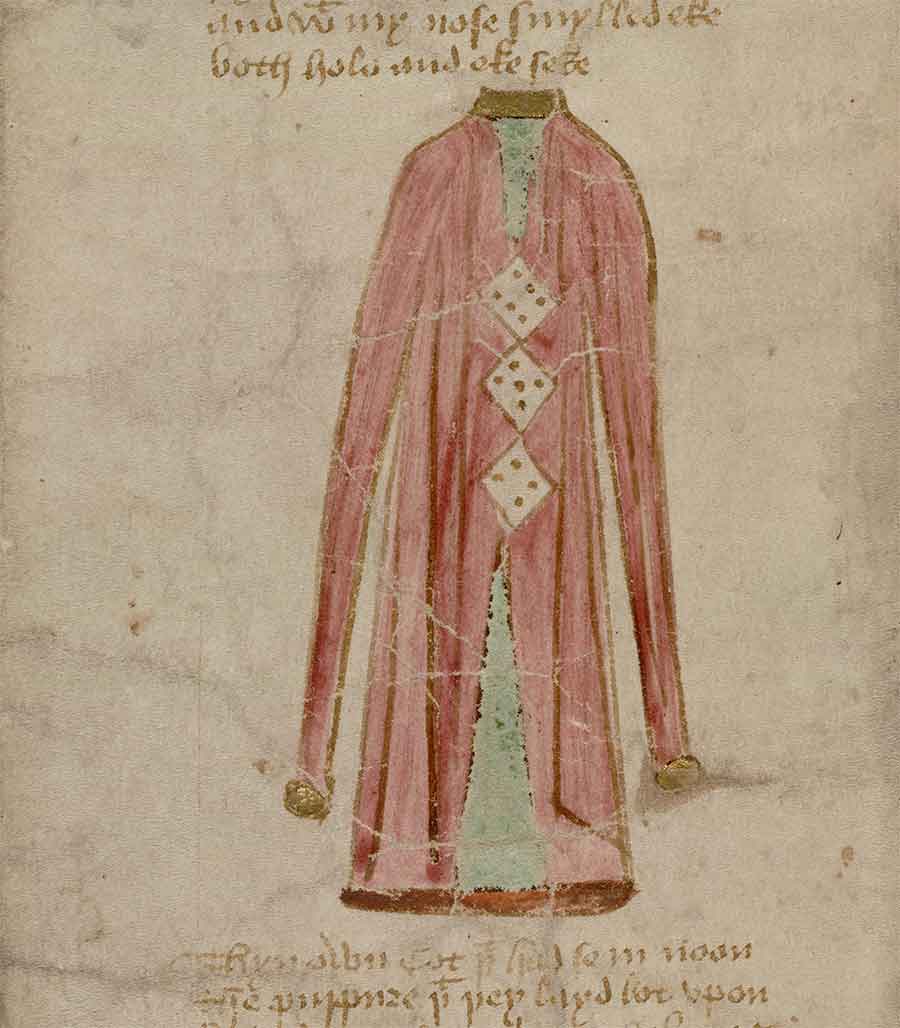

This detail from the manuscript shows Christ's garment, along with the dice that Roman soldiers are said to have used to gamble for it. In the "O Vernicle" stanza below the garment, these objects are used to help protect the speaker from wearing or coveting inappropriate clothing.

My interest in this poem originated in one particular stanza, the verses that deal with Christ's garments. In the Bible, Christ wears two main items of clothing. The tunica inconsutilis, or "unseamed tunic," is Christ's own garment, so called because it was made without a seam, meaning that it was not made by a human hand; the vestis purpurea, or "purple garment," is the garment in which he is dressed during his mocking, when his captors ridicule him by costuming him like a king. Each of the four gospels in the New Testament tells the story of the soldiers who play lots (gamble) for Christ's garment. As the story goes, right after the crucifixion itself, the soldiers decide to divide the seamless garment among themselves; when they realize that it has no seams (and thus cannot easily be divided), they instead play lots to see who will take the whole garment. The episode is a crucial one in the story of the Passion, and it is usually understood to symbolize the indivisible unity of the body of Christ and of the Church.

But in the arma Christi poem, this biblical episode takes on new meaning. The poem mentions the seamless garment, but it insists that the purple garment is the one the soldiers gambled for. This was an easy switch to make: Christ's seamless robe was, we are to understand, simple and unadorned, whereas the purple robe used to mock him was made of the most luxurious and valuable materials—those only a king could afford. If the soldiers were going to fight over a garment, the purple one seems like the more obvious choice. The poem offers up the contrast between Christ's two very different garments, therefore, as a point of contemplation for people who might desire beautiful but morally dubious things. A related stanza is reproduced here in its original Middle English and in a modern English translation:

Thyn own cot þt had sem noon

The purpure þt þey layd lot upon

Lorde be my socoure & my helpynge

Þt my body hath used mys clothynge.

Your own coat that had seams none,

The purple one that they laid lots upon:

Lord, be my succor and my helping

That my body has misused clothing.

Here the speaker's description of Christ's garments (he or she speaks directly to Christ, calling the garment "Your coat") invokes a kind of protection against the vice of "misused clothing," which could have meant anything from coveting beautiful clothing to wearing clothes that were expensive, luxurious, or fashionable. Look at Christ's clothing, the stanza says, and contemplate more carefully the clothes that you yourself wear or covet.

This stanza is especially interesting because of the image that accompanies it. Unlike most English poems written during this time, the arma Christi poem is almost always illustrated. Christ's purple garment is one of the larger illustrations in HM 26054, and the dice associated with it (dice, in the Middle Ages, having replaced the lots described in the biblical narrative) have been superimposed on the garment itself, as if meant to represent buttons or brooches. Like the nails illustrated later on in the poem, the dice are depicted as life-size—the size of actual medieval dice—ostensibly to enhance their effect as objects of meditative concentration.

Andrea Denny-Brown, former Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Fellow at The Huntington, holds the silk purse that contains the arma Christi manuscript. Photograph by Kate Lain.

A STARTLING REALIZATION

The roll format of manuscripts of this poem has always intrigued and mystified scholars. One of its earliest critics, Rossell Hope Robbins, suggested in 1939 that the roll format was meant for congregational use, to be hung in churches for public worship. Most recent scholars have rejected this understanding, arguing that the poem's form, words, and images seem best suited for private devotion such as prayer, introspection, and meditation. For one thing, the various manuscripts of the poem are relatively small—too small for their images and words to be observed from the congregation if they were hung on a church wall. The poem's language, including the personal way the speaker of the poem addresses Christ as "you," also suggests a more intimate reading experience. Many stanzas invoke the reader's experience of his or her five senses, yet another personal element: the blindfold that was used to cover Christ's eyes during his mocking, for example, offers contemplation of vices experienced through the reader's eyes and nose; the nails used in the crucifixion serve as objects of meditation about sins perpetrated by one's hands and feet. The tongs used to remove the nails after Christ's death are also included in the poem, portrayed as instruments that can help "loosen" any sins from the poem's speaker or reader, just as they helped physically to loosen Christ from the cross.

But this manuscript seems to have had an even more unique personal use. Scholar Mary Agnes Edsall has recently published evidence that the most narrow arma Christi rolls were likely used for an astonishing purpose: as birth girdles, textual talismans that could be wrapped around a woman's belly to protect her and her baby during labor. Such girdles were made from long strips of parchment sewn together, like The Huntington's manuscript, and they usually included prayers, charms, and spiritual symbols, such as the arma Christi. This would explain not only the curiously long and narrow size and shape of The Huntington's manuscript, but also its obvious portability and well-used physical condition: this manuscript had a practical function. It likely belonged to a medieval midwife or a female family member, perhaps passed down through generations of women in the same family or line of work.

The Arma Christi in Medieval and Early Modern Material Culture With a Critical Edition of "O Vernicle" opens with an introduction that surveys previous scholarship and situates the arma Christi in their historical and aesthetic contexts. The 10 essays that follow explore representative examples of the instruments of the Passion across a broad swath of history, from some of their earliest formulations in late antiquity to their reformulations in early modern Europe. Together, they offer the first large-scale attempt to understand the arma Christi as a unique cultural phenomenon of its own, one that resonated across centuries in multiple languages, genres, and media.

This manuscript pulls out all the stops—it synchronizes the power of words, images, and objects—to ask for, and to offer, spiritual guidance and protection for a human life necessarily lived among material things. Such a call for supernatural protection is equally apt for a mother facing the very real dangers of illness or death during labor and for a child about to enter the world for the first time. As a birth girdle, the Huntington manuscript known as HM 26054 would have served both purposes admirably, and—in my somewhat biased opinion—exquisitely.

OUT OF THE PURSE AND INTO PRINT

Almost 10 years after encountering my first arma Christi manuscript, I finally started a book project with my colleague and co-editor Lisa H. Cooper in an attempt to explain not only HM 26054, but also all kinds of other curious medieval and Renaissance objects that used the arma Christi as their central unifying theme: manuscripts, heraldic shields, tombstones, sculptures, textiles, paintings, and printings. We invited junior and senior scholars from many disciplines to think through the cultural and artistic uses of these objects, and with them, we produced the first critical volume to address the arma Christi as its own cultural phenomenon. Part of this project was to produce, with scholar Ann Eljenholm Nichols, a new critical edition of the poem I first encountered in that green silk purse—now renamed "O Vernicle," for the opening line of the poem, which is about Veronica's veil. The book, published by Ashgate and titled The Arma Christi in Medieval and Early Modern Material Culture: With a Critical Edition of 'O Vernicle,' represents a very happy conclusion to one of my most felicitous early encounters with The Huntington's medieval manuscripts.

Andrea Denny-Brown is associate professor of English at University of California, Riverside, and a former Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Fellow at The Huntington.